South Africa

A story of South Africa: Mining, Migration, Misery

Mining and migration have gone hand in hand since the Neolithic era, but the special impact of industrial strength mining and Apartheid brought special characteristics and problems that live on to today. J. BROOKS SPECTOR contemplates the result.

Back in the mid-1970s when this writer first came to South Africa to work, one of the things that seemed mandatory to do was to visit some of the country’s famous – or infamous – diamond and gold mines. Reading about them was one thing, but even reading all those “Jim Comes to Joburg”-style novels of struggle and survival on the mines by migrants from rural areas or carefully examining a book like “On the Mines” – the one with those evocative David Goldblatt photographs paired with Nadine Gordimer’s essay (“Mines of the beloved country: Through the mind of a photographer and essayist”) – did not prepare one for the reality of it all meant that came from actually visiting working mines.

Then, as it happened, in 1975, the Chamber of Mines went on a kind of charm offensive (perhaps as if to say, “The mines aren’t bad places, just misunderstood ones”). They extended an invitation to visit a working gold mine in the Johannesburg area. This was to be no quick trip down that decommissioned touristy mineshaft at Gold Reef City, a place that was only set up much later anyway. Instead, this was a day-long visit to a typical gold mine, complete with a trip down the mine lift to a working gold seam where the miners were drilling the ore from out of the rock face, loading the resulting rocks onto the cocoa pans and then on to the areas where new blasting was being prepared. (And, yes, visitors had to sign a waiver of indemnity over practically every possibility that might befall them.)

Before going down the shaft, the tour also included time to see the hostels for the migrant workers – as well as a stop at the mine store and even the traditional beer hall on the mining compound’s premises. What was weird, maybe even remarkable, was that this tour seemed designed to show off this particular mine as an example of progressive, fair treatment of its complement of migrant workers. This was in spite of the palpable sense of overcrowding, the weary, worn-out grunginess of the ablution area and those miners’ sleeping shelves – no, not beds – shelves, made out of concrete. Really.

Walking through the compound, and then descending into the stygian depths of the mine, made it impossible not to recall George Orwell’s classic “The Road to Wigan Pier”, that 1930s masterpiece of outraged, investigative journalism, quite literally from the actual coal face. Orwell had gone north to the English Midlands – as a freelance journalist – to investigate for himself the conditions of coal miners. While staying as a boarder in a rooming house, he had gotten to know the miners and had gone down coal mines several times to get a truer measure of the work of the miners, beyond his observations of the miner families’ living conditions.

After describing the appalling conditions of miners’ homes and lives above ground, Orwell had written his report about the actual mine work, saying, “Even when you watch the process of coal-extraction you probably only watch it for a short time, and it is not until you begin making a few calculations that you realise what a stupendous task the ‘fillers’ are performing. Normally each man has to clear a space four or five yards wide. The cutter has undermined the coal to the depth of five feet, so that if the seam of coal is three or four feet high, each man has to cut out, break up and load on to the belt something between seven and twelve cubic yards of coal. This is to say, taking a cubic yard as weighing twenty-seven hundred-weight, that each man is shifting coal at a speed approaching two tons an hour.”

And he had added, “I have just enough experience of pick and shovel work to be able to grasp what this means. When I am digging trenches in my garden, if I shift two tons of earth during the afternoon, I feel that I have earned my tea. But earth is tractable stuff compared with coal, and I don’t have to work kneeling down, a thousand feet underground, in suffocating heat and swallowing coal dust with every breath I take; nor do I have to walk a mile bent double before I begin. The miner’s job would be as much beyond my power as it would be to perform on a flying trapeze or to win the Grand National. I am not a manual labourer and please God I never shall be one, but there are some kinds of manual work that I could do if I had to. At a pitch I could be a tolerable road-sweeper or an inefficient gardener or even a tenth-rate farm hand. But by no conceivable amount of effort or training could I become a coal-miner, the work would kill me in a few weeks.”

After descending in the miners’ cage as it hurtled down hundreds of meters and then walking to the ore face in that gold mine, I felt I understood exactly what Orwell had felt himself. And to be truthful, the life at that gold mine did not seem appreciably better for its workers than the lives of those British miners had endured forty years earlier in the midst of the Great Depression. And almost certainly, it was much worse than that of the coal mines in the English Midlands back in the 1930s in many important ways.

And then there was that working diamond mine in Kimberley. I had been in that city, escorting a young American poet for readings in little towns and cities across the country and fortuitously was invited by the mine’s top manager to see the mine for myself. This time one had to change into mining overalls and boots rather than one’s own rough clothing.

The point of course was that unlike a gold mine where the ore concentrations are so low nobody could really carry out enough ore on their own to buy a cup of coffee, a diamond mine is very different creature. One lucky find and a miner might conceivably discover something a little bigger than a pigeon’s egg and retire on the proceeds, just as long as its discoverer could tap into the illicit diamond trade.

As a result, when one came back out of a diamond mine, it was time to turn in the overalls and then get your own clothing back. Of course miners were examined rather more carefully, I learned, if there was the slightest hint of some individual entrepreneurial activity.

In Kimberley, too, the basic plan had been essentially the same, even if the general conditions of that compound were slightly easier on the eye. Black workers were still recruited from far away, then signed to contracts that moved them to the mine and away from families, kept from the better-skilled jobs and training for such jobs by both law and mine custom, housed in company compounds, and provided the opportunity to visit their families twice a year. From such arrangements the familiar roster of economic and social ills has inevitably followed.

But was all this – the vast migrant worker streams of lower-skilled, poorly paid workers, those inhospitable men-only compounds, the mine dance competitions designed to focus energies away from the miners’ actual economic circumstances, and all the rest of the system – inevitable? Of course it wasn’t.

Consider that throughout human history from the Neolithic era onward, men have been discovering metallic ores and then moving themselves to new site to dig a mine to extract the ore and process it to higher value material as close to the mine source as possible for the sake of efficiency in trading and working with it. Eventually, miners would bring their families to the new mine, or establish new families, and a community would spring up for as long as the ore was productive – or even longer if other industries came on stream.

When the valuable material being mined finally ran out, went too deep into the earth to be mined effectively, or the concentration became too low to be worth extracting, the community would shrink and the people would eventually move away to better opportunities elsewhere – or, more occasionally, figure out a way to turn to new industries. There are ghost towns all around the world as a result of this natural rhythm of mining.

For example, within two years after the mother lode of the gold in central California had been discovered shortly after California had been captured from Mexico by the US, the territory had attracted so many people it qualified for statehood in 1850. And so many people had flooded into San Francisco, the port nearest the gold fields, the harbour was filled with ships whose very crews had deserted to work the gold fields rather than re-join their ships for the return voyage to the eastern part of America. The gold ore no longer attracts the hundreds of thousands who came there originally to work the hills and streams in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains (any gold mining there now is largely mechanised or is carried on by part-time hobbyists), but San Francisco and Sacramento still are big cities.

Less than twenty years after the big gold strike in California, the real sources of diamonds that had been found in dry streambeds near the Orange River, had been discovered. This was the kimberlite “blue earth” pipes in the Kimberley area that were the remnants of veins of carboniferous rock occurring within the hardened lava from long-extinct volcanoes from eons before.

Thereafter, there was a massive diamond rush to the area as miners and fortune-seekers streamed to Kimberley from all over the world., and the site became the diamond boomtown of Kimberley. This fuelled South Africa’s first major mineral rush, the consequent industrialised mineral exploitation of these deposits, and a struggle over who would control the diamond fields – the Orange Free State, or the British Empire. Among other things, Kimberley actually became the first southern African city with electric streetlights. And it set the stage for the highly industrialised mining processes to follow further north when gold was discovered in major quantities of low-grade ore.

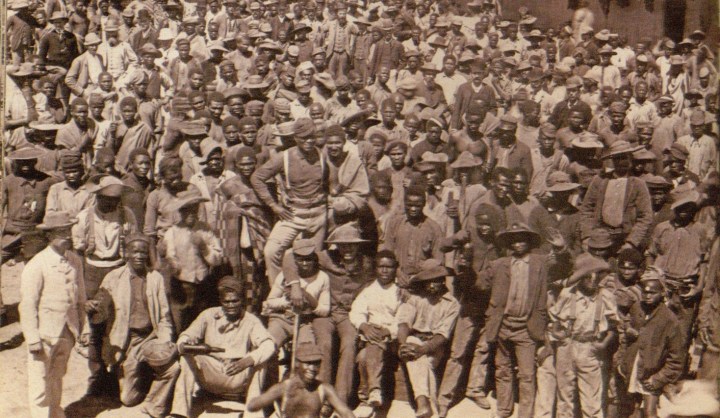

Because the Kimberley mines were exploiting the actual diamond-bearing ores, they became characterised by large-scale industrial processes and the mobilisation of international capital almost from the beginning. Diamond mining had such a massive impact on the entire Southern African region that, as economic historian William Worger described it, “within a year of the opening of the mines, every black society south of the Zambezi River, with the exception of the Venda and Cetshwayo’s Zulus, was represented at the diamond fields, whether by labourers, artisans, or independent businessmen.” And just two decades after Kimberley, there followed that major gold strike on the Witwatersrand, including what became the city of the new Johannesburg.

But unlike California, or any number of other mineral strikes around the world, in South Africa, by virtue of the combination of the country’s increasingly segregated society, the early industrialisation of mining and its consequent control by large corporations, and the push-pull of a desire for the wages to purchase goods as well as the need for cash to pay government-imposed taxes on black families, these pressures drove black workers to sign on to work on the mines, far from their homes. These factors drove miners to work the mines, but they also had to leave their families far behind in order to do so.

Instead of establishing flourishing, racially polyglot new cities – somewhat like, say, San Francisco – around the mines and the industries connected to mining, mine operators and civil administrators regulated the flow of workers and largely restricted them from establishing permanent residence near the mines, let alone bringing their families there, or even establishing new families for permanent residence. By the time Apartheid’s regulations came into full force, the system had congealed into an intricate system of cyclical recruitment and return of miners from throughout the country to the mines and then home again on those twice-yearly holidays and yearly contracts.

In the heyday of the mining industry’s employment of a half million workers or more, they were coming from the northern parts of the Transvaal, Zululand and the Eastern Cape. And the mines also recruited workers by the hundreds of thousands from countries throughout Southern Africa.

The mining industry, of course, used this process to keep labour costs down and to prevent a permanent class of black miners in and around the mining cities from taking root. And because the miners were hired on a yearly basis, seniority was never as strong it was among the white, more privileged workers who lived permanently, close to the mines, and who had more secure forms of job tenure.

Today, of course, the mines in and around Johannesburg have largely been played out, save for the highly mechanised reprocessing of the old mine tailings to extract any remaining ore or by the work of illegal miners digging in shafts that have been formally decommissioned. The number of gold miners and gold output continues to decline as well, although mining still represents over 40% of SA’s export earnings.

But the gold mining labour system was largely replicated on the platinum belt to the northwest as well. Even now, a majority of miners in the Northwest Province are recruited from well beyond the areas of the mines. These miners still repatriate the bulk of their earnings back “home” – even if they have now established a more permanent kind of temporary residence, using the “living out” payment system the mines now offer as an housing alternative, instead of the mandatory use of those old-style temporary workers’ hostels.

But the whole system still conspired to prevent the creation of permanent, settled communities of miners who were digging the platinum; and the discontents of those miners over wages and working conditions eventually led to the Marikana massacre, as well as the strikes in the sector at present – as has been so thoroughly reported in The Daily Maverick since 2012.

Still buried deep in the heart of this discontent would seem to be the lack of any permanent roots where the miners work, their fears that jobs are growing ever scarcer, and that their pay packets still remain well below acceptable levels. At the same time, the mine operators look over their shoulders at rising operating costs and the fluctuating international prices for platinum, as they contemplate the costs and benefits of settling with the miners or shutting down the shafts entirely.

Many activists argue that South African miners’ wages are far too low for local conditions to support a decent but modest life, let alone seem in comparison with mining wages in places like Australia and Canada (but not China). The current AMCU-led strike (after that new union had largely replaced the older NUM on the platinum belt) has centered on demands for salaries to reach R12,500 per month within the next five years. Mining houses have responded that at that level, they would need to retrench thousands of workers or shut down entirely. They further argue that Canadian and Australian wages are higher because such miners are more highly skilled and that they operate in highly mechanised conditions so that there are fewer workers overall.

But as things stand now, the struggle on the platinum mines is the cumulative buildup of the after-effects of Apartheid social planning as well as growing pressures for better wages – and the growing fear platinum mining may not, ultimately, be forever. Increases in alternative fueled motor vehicles may cut down the demand for that metal for catalytic converters, and the recycling of platinum and the use of alternative metals for converters will negatively affect demand even further.

And then what will happen when miners can no longer even migrate to the platinum belt for their labours? Absent a whole new way of thinking about how these mines might work, the difficulties can only grow worse. DM

Read more:

- The Stuff of Legends – Diamonds and development in southern Africa, a research report from Business Leadership South Africa

- The Road to Wigan Pier, by George Orwell

- Transkei’s surprising response to Marikana, a column by Jonny Steinberg in Business Day

Photo: Miners of De Beers mine in Kimberley, 19th century.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider