Maverick Life

Pete Seeger, finally overcome at 94

One of America’s most influential – and unique – musical talents finally put down his guitar, banjo and pen for the very last time, passing away on Monday, 27 January at the age of 94. Seeger had lived through two folk music booms, written tunes that became some of rock music’s most important tunes and popularised, penned or adapted the civil rights revolution’s most iconic anthem. Along the way, he never shied away from the radical politics that made him both a legend and (sometimes, with some people) a political outcast. He even had a crucial role in environmental protection – helping lead the charge for the clean-up of a thoroughly polluted Hudson River. J. BROOKS SPECTOR looks back at a creative life well lived.

Throughout his very long life, Pete Seeger always felt drawn to the downtrodden, the economically, racially or politically bullied, the marginalised – and each new generation of young people. Ironically, after he had joined yet one more march, this time on behalf of the Occupy Wall Street movement, walking on his crutches, Seeger told reporters, “Be wary of great leaders. Hope that there are many, many small leaders.”

Seeger was born in New York City on 3 May 1919 and his family traced their roots back to the earliest religious dissenters of colonial America. His mother was a violinist and his father was a musicologist who had been instrumental in providing work for indigent artists via federal government relief programs during the Great Depression. An uncle, Alan Seeger, had authored the well-known poem, “I Have a Rendezvous With Death.”

Seeger himself always told people he first fell in love with folk music as a sixteen-year-old when he had attended a music festival in North Carolina in 1935 with his father. Describing that moment, Seeger said, “I liked the strident vocal tone of the singers, the vigorous dancing. The words of the songs had all the meat of life in them. Their humour had a bite, it was not trivial. Their tragedy was real, not sentimental.”

Along the way, he learned the twelve-string guitar and the five-string banjo, an instrument he rescued from virtual obscurity. Throughout his life, he played a long-necked version of the banjo that he had designed himself. His banjos always carried the mantra, “This machine surrounds hate and forces it to surrender” – a symbolic acknowledgement of his friendship with Woodie Guthrie whose own guitar had carried the slogan, “This machine kills fascists.”

Seeger had entered Harvard University in 1936 to study sociology but dropped out two years later, hitting the road to pick up folk tunes as he hitchhiked or rode freight trains throughout the country. Many years later he told reporters his sociology professor had said to him, “Don’t think that you can change the world. The only thing you can do is study it.” That advice sufficiently disillusioned him that it helps explain his decision to study the nation’s musical heritage first-hand, rather than from university study.

The Guardian, in an earlier interview with Seeger had reported, “Guthrie, he says, taught him how to busk. ‘He’d say put the banjo on your back, go into a bar and buy a nickel beer and sip it as slow as you can. Sooner or later, someone will say, “Kid, can you play that thing?” Don’t be too eager, just say, “Maybe, a little.” Keep on sipping beer. Sooner or later, someone will say, “Kid, I’ve got a quarter for you if you pick us a tune.” Then you play your best song.’ With that advice, Seeger supported himself on his travels.”

Together with Woody Guthrie and several other friends, he formed the Almanac Singers in 1940, and they performed concerts for disaster relief and various left-wing causes around the nation. Later, he and Guthrie toured migrant worker camps (like the ones described in John Steinbeck’s “The Grapes of Wrath”), performed on radio for the government’s overseas broadcasts during World War II, and then he spent over three years in the Army, entertaining troops throughout the South Pacific theatre of war. Along the way, he married his Japanese-American wife, Toshi-Aline Ohta, in 1943 and they built a cabin in the town of Beacon, overlooking the Hudson River where they raised their family and lived for decades.

Later on in life, he helped energise efforts to clean up the polluted Hudson River, using his fame to goad politicians into action. He sailed the sloop Clearwater, built by volunteers back in 1969, up and down the Hudson River, singing to raise money to clean the water and fight polluters. This effort eventually forced General Electric to pay half a billion dollars for the removal of toxic substances in the water.

After World War II, Seeger founded the company, People’s Songs Inc., which published political songs and presented concerts for several years before going bankrupt. He also began his nightclub career at that time as well, performing at the Village Vanguard in Greenwich Village. Seeger and Paul Robeson also toured with the campaign of Henry Wallace, the Progressive Party presidential candidate in the 1948 election that was won by Democratic incumbent president, Harry Truman.

In his wide-ranging musical output, Seeger wrote (or co-wrote) such great rock and protest standards as “If I Had a Hammer,” “Turn, Turn, Turn,” “Where Have All the Flowers Gone” and “Kisses Sweeter Than Wine” – songs that have been performed (and recorded) by innumerable other singers. And he adapted the civil rights anthem, “We Shall Overcome” from earlier gospel sources so powerfully that it became the soundtrack for decades of marches and protests. Seeger modestly said years later that his only real contribution to the creation of this theme song for the civil rights movement was to change the second word from “will” to “shall,” a change he explained, “opens up the mouth better.”

Watch: Pete Seeger talks about the history of “We Shall Overcome” (2006)

In summing up his life, the New York Times wrote Seeger had been “a mentor to younger folk and topical singers in the ‘50s and ‘60s, among them Bob Dylan, Don McLean and Bernice Johnson Reagon, who founded Sweet Honey in the Rock. Decades later, Bruce Springsteen drew the songs on his 2006 album, ‘We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions,’ from Mr. Seeger’s repertoire of traditional music about a turbulent American experience, and in 2009 he performed Woody Guthrie’s ‘This Land Is Your Land’ with Mr. Seeger at the Obama inaugural. At a Madison Square Garden concert celebrating Mr. Seeger’s 90th birthday, Mr. Springsteen introduced him as ‘a living archive of America’s music and conscience, a testament of the power of song and culture to nudge history along.’ ”

Throughout his long career, he also recorded albums of African folksongs, edited a popular songbook of these materials, and transformed “Mbube” into “Wimoweh”. He had heard a recording of it by Solomon Llinda and, unable to capture the word, “mbube” correctly, had transcribed it into “wimoweh” instead. “Wimoweh” became a mega-hit in the US and beyond, with the song eventually covered by over 250 other musicians. Years later, Seeger learned the song was not the authorless traditional tune he had originally thought it was. (Meanwhile, George Weiss, then president of ASCAP, had registered a copyright on the song as a result of his own additions to the work and “Wimoweh/Mbube” became the subject of a protracted legal struggle to deliver payments to the original composer’s descendants.)

With the formation of his folk quartet, The Weavers, in 1948, Seeger had helped set in motion a new national folk revival, His old pal’s son, Arlo Guthrie, once said, “Every kid who ever sat around a campfire singing an old song is indebted in some way to Pete Seeger.”

For Seeger, his musical and political activism were always tightly bound together – in part from his social conscience and in part from the content and subjects of the songs he loved. A member of the Communist Party in his youth, Seeger moved away from the party around 1950 and eventually renounced the body. but those early associations gave him endless trouble for years.

Because of those associations, he ended up being barred from appearing on American commercial television for over a decade, after he had locked horns with the House of Representatives’ Un-American Activities Committee in 1955. Pushed hard by committee members to testify as to whether Seeger had ever sung on behalf of communists and communist causes, he had angrily retorted, “I love my country very dearly, and I greatly resent this implication that some of the places that I have sung and some of the people that I have known, and some of my opinions, whether they are religious or philosophical, or I might be a vegetarian, make me any less of an American.” He ended up being charged with contempt of Congress, but the sentence was eventually overturned on appeal.

While he was off the television screens for years, Seeger later said those years became a high point of his career as he toured university and college campuses across the country with the music that he, Guthrie, Huddie “Lead Belly” Ledbetter and others had created or preserved. A few years ago, Seeger had told reporters, “The most important job I did was go from college to college to college to college, one after the other, usually small ones…. And I showed the kids there’s a lot of great music in this country they never played on the radio.” The Times noted, “By then, the folk revival was prospering. In 1959, Mr. Seeger was among the founders of the Newport Folk Festival. The Kingston Trio’s version of Mr. Seeger’s ‘Where Have All the Flowers Gone?’ reached the Top 40 in 1962, soon followed by Peter, Paul and Mary’s version of ‘If I Had a Hammer,’ which rose to the Top 10.”

He finally returned to network TV on a widely watched episode of the “Smothers Brothers” variety show program in 1967, in the midst of growing national discontent over the war in Vietnam. But, in that appearance, the network cut Seeger’s anti-Vietnam War protest song, “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy” from the broadcast. Half a year later, he was back on the “Smothers Brothers” show and this time he sang his song on air this time, although one local affiliate cut the especially bitter final stanza that protested the futility of the Vietnam War: “Now every time I read the papers/That old feelin’ comes on/We’re waist deep in the Big Muddy/And the big fool says to push on.”

By the 1990s, Seeger had become a national icon, almost regardless of those earlier, vitriolic political issues. In 1997 he won a Grammy for the best traditional folk album, “Pete.” Appearing at Washington, DC’s Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in 1994 to receive his lifetime achievement honours, President Bill Clinton praised Seeger as “an inconvenient artist who dared to sing things as he saw them”. He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame two years later, and he became the inspiration for Bruce Springsteen’s 2006 album, “We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions,” a reinterpretation of some of Seeger’s trademark songs. And the 2009 concert at Madison Square Garden, marking Seeger’s 90th birthday, brought together performers like Springsteen, Dave Matthews, Eddie Vedder and Emmylou Harris to honour him. Towards the end of his life, in 2009, he even performed on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial at an inaugural concert for Barack Obama.

As far as the famous tale of Seeger, Dylan and the axe, Seeger often denied he intended to take an axe to Bob Dylan’s amplified sound equipment at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival due to his dislike for Dylan’s new “electric” sound. Seeger always insisted his only anger was because the resulting guitar mix was so loud he couldn’t hear Dylan’s words over the other sounds.

Virtually until the end of his life, Seeger lent his name or spoke up to oppose the injustices he disliked most, believing his music and his presence had helped breathe life into those protests. As he had said four years ago, “Can’t prove a damn thing, but I look upon myself as old grandpa. There’s not dozens of people now doing what I try to do, not hundreds, but literally thousands…. The idea of using music to try to get the world together is now all over the place.” Not a bad epitaph for a commitment to the music he loved so much and the social and political causes he felt so strongly about throughout his life. DM

Read more:

- Folk singer, activist Pete Seeger dies in NY at the AP

- Pete Seeger, Songwriter and Champion of Folk Music, Dies at 94 at the New York Times

- Pete Seeger, legendary folk singer, dies at 94 in the Washington Post

- US folk singer Pete Seeger dies – Pete Seeger Pete Seeger continued to perform well into his nineties at the BBC

- Folk Music Legend Pete Seeger Dies at 94 at Variety

- Pete Seeger: ‘Bruce Springsteen blew my cover’ at the Guardian

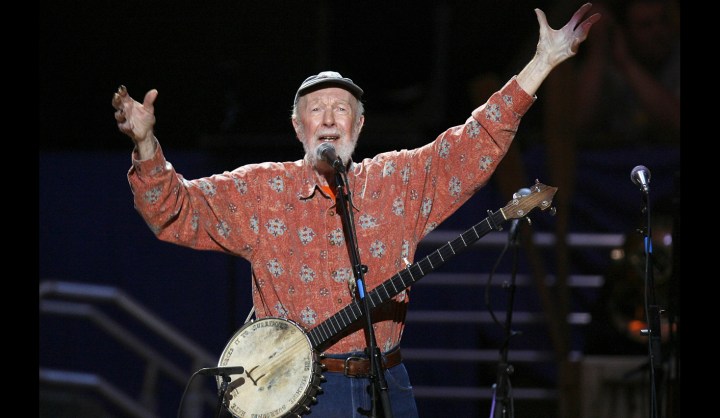

Photo: Pete Seeger sings Amazing Grace during a concert celebrating his 90th birthday in New York May 3, 2009. The concert at Madison Square Garden had an all-star roster of performers with proceeds to benefit Hudson River Sloop Clearwater, a non-profit corporation founded by Seeger in 1966 to bring environmental attention to the Hudson River Valley. REUTERS/Lucas Jackson

Become an Insider

Become an Insider