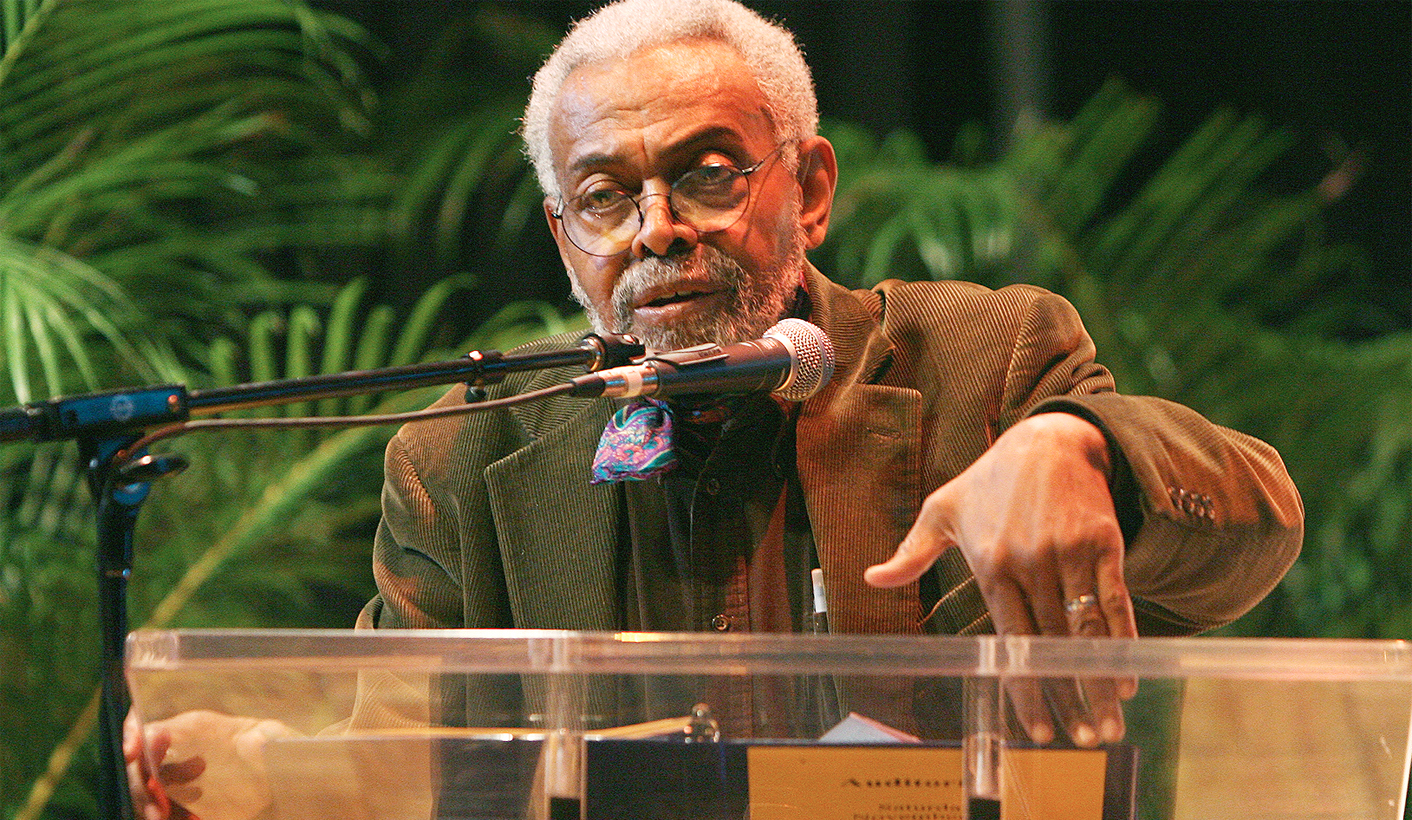

Amiri Baraka, the man whose angry, blues-based dramas, poetry and criticism made him a precedent-setting, cultural agent provocateur, passed away last week at the age of 79. Baraka – and, as LeRoi Jones, before he had changed his name – had inspired several generations of poets, playwrights and musicians, both in America and further afield. His use of spoken word traditions and a bold, raw, edgy street-wise language helped set the stage for the rap, hip-hop and slam poetry explosions that came after his own peak periods of creativity.

His cultural influence was so big that in the 1960s the FBI had even dubbed him “the person who will probably emerge as the leader of the Pan-African movement in the United States.” Pretty high praise – in a backhanded kind of way – for a playwright-poet!

Baraka was one of the rare African Americans who transitioned from the wild enthusiasms of Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac’s Beat generation of the 1950s and early ‘60s to become a seminal figure in the Black Arts Movement. This movement was an artistic and cultural ally of the Black Power movement that had starkly rejected the optimistic racial consensus of the early '60s, contributing to an increasingly heated division over how and why black artists should address and critique the nation’s social issues.

Roughly shucking off an art for art's sake aesthetic that appealed to many writers, as well as the presumed chimera of progress towards black-white racial unity, Baraka – as he was now known – moved sharply away from his earlier Beat sensibility. Instead he became a leading proponent for the teaching of a thoroughly Afro-centric approach to black art and black history - and then on to the production of works that were a call for revolution. His “Black Art” manifesto of 1965 had famously solicited “poems that kill” in the same year that he also helped breathe life to the Black Arts Movement. Sounding something like an angrier, racially flavoured, contemporary version of Walt Whitman’s “barbaric yawp”, Baraka wrote, “Assassin poems. Poems that shoot guns/Poems that wrestle cops into alleys/and take their weapons leaving them dead/with tongues pulled out and sent to Ireland.”

Over his long creative life, Baraka ultimately drew upon diverse array of influences – a range as eclectic as his work was prolific. These included science fiction writer Ray Bradbury and Chinese leader Mao Zedong, Beat poet Allen Ginsberg, and jazz musician John Coltrane. And over this career, Baraka had written poems, short stories, novels, essays, plays, musical and cultural criticism - and even jazz operas.

His 1963 book, “Blues People”, has been cited as the first major history of black music written by an African-American. Reviewing this volume, folklorist Vance Randolph had said in The New York Times Book Review, “The book is full of fascinating anecdotes, many of them concerned with social and economic matters,” commending it for its “personal warmth.”

His words always seemed to find a nerve. A line from his poem “Black People!” – “Up against the wall motherf---” — became a ubiquitous counterculture verbal touchstone for an entire generation - everyone from anti-Vietnam War student protesters to the acid rock band, The Jefferson Airplane. And, then, of course, there was his 2002 poem (see full text following this story) alleging Israelis had somehow had advance knowledge of the 9/11 attacks on the Twin Towers in New York City. This led to widespread outrage and politicians and others demanded Baraka be relieved of his largely symbolic honour as New Jersey’s poet laureate – Baraka’s home state.

By turns, Baraka’s detractors called him buffoonish, homophobic, anti-Semitic, and demagogic. But his supporters had a very different view. They labelled him a genius, a prophet, and American literature’s Malcolm X. Writer Ishmael Reed, for example, credited the Black Arts Movement – Baraka’s long-time literary home - as helping give rise to the new sensibility of multiculturalism in American literature and academia. And renowned literary scholar, Arnold Rampersad, put Baraka’s importance right up there with the renowned 19th century anti-slavery leader and autobiographer Frederick Douglass or novelist Richard Wright among the top pantheon of America’s black cultural influences. And Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright August Wilson had said of him, “From Amiri Baraka, I learned that all art is political, although I don't write political plays.”

LeRoi Jones made his first entries in print, back in the 1950s, as part of the Beat movement. But in 1964 - just before he changed his name and embraced Islam – Jones’s presence exploded like hot shrapnel across the literary landscape, when his one-act play, Dutchman, opened at the Cherry Lane Theater in New York City’s Greenwich Village – right in the midst of America’s civil rights movement.

The play takes place inside a New York City subway car, with a showdown between a quiet middle class black man, Clay, and a sexually daring and clearly unbalanced white woman, Lula. Their collision ends in a fight of murderous taunts and confessions. Described by some critics as a twist on the Biblical Adam and Eve story (or perhaps more properly the alternative tale of relationships between Adam and Lilith), the play also seemed to channel America’s increasingly corrosive black-white relationship. Perhaps, too, it drew some of its dazzling and frightening potency from the fact that Jones’ own marriage to a white, Jewish woman, Hettie Cohen, was beginning to unravel.

Hilton Als, writing about Dutchman and its creator’s world in The New Yorker, said, “The Obie-award winning play was written in one night, as though in a fevered dream. Set in the New York City subway—a modern circle of hell—the play centers on two characters: Clay, a middle-class, black intellectual, and Lula, a somewhat loose, blond white woman who eventually does away with Clay and his pretensions and his rage towards his white seductress by violently killing him. Writing in his 1984 Autobiography, Jones said that Dutchman was prompted by his desire to make his poetry feel more active; he wanted his plays to move. It was a brilliant decision. Between 1964 and 1967, Baraka wrote three plays of astonishing originality—and pain. Equal parts Living Theatre, spoken-word art, and raw, natural theatrical talent, the plays ricocheted between realism and surrealism, plain-spoken metaphor and dense, concrete riffs about various kinds of love: gay love, a fascination with power, blood lust.”

Dutchman was first produced when the writer was still calling himself LeRoi Jones. But the cumulative impact of his response to the political and social developments of Castro’s Cuba after his visit there in 1960, then Malcolm X’s 1965 assassination, and then, finally, the violent race rioting in his home town of Newark, New Jersey in 1967, as Baraka himself had been briefly jailed in the aftermath, all seemed to send him off in a very different direction in his life. The net result of all of this collectively helped bring about his increasing political radicalisation and the assumption of his new Islamicised name.

At this point, he left his first wife, broke his ties with his white friends, and moved from the avant-garde world of Greenwich Village to New York City’s thoroughly black district of Harlem. At this time, he gave himself his new name, Imamu Ameer (later changed to Amiri) Baraka – meaning “spiritual leader blessed prince” – and then publicly denigrated Rev Martin Luther King Jr. as a “brainwashed Negro.” He helped organise the 1972 National Black Political Convention and founded Afro-centric community arts and political groups in Harlem and Newark.

Baraka’s Black Arts Movement essentially came to an end in the mid-1970s, and Baraka eventually dialled back from some of his more acerbic comments about Martin Luther King and gays – and as well as whites more generally. Nevertheless, as filmmaker Spike Lee was directing his major biopic of Malcolm X in the early 1990s, Baraka charged that Lee was “a petit bourgeois Negro” unworthy of his film’s protagonist.

Nevertheless, despite all the controversies, by the early 2000s, Baraka’s literary reputation had grown such that he could be named New Jersey’s poet laureate - only to generate a new and acrimonious public uproar in 2002 with his poem, “Somebody Blew Up America.” The New Jersey governor and state government, after learning they could not legally dismiss Baraka from this honour amidst the commotion, eventually did away with the honorary post entirely rather than keep Baraka in that seat. Meanwhile, Baraka blasted critics who had charged his poem had represented anti-Semitic views. He insisted such comments were a “dishonest, consciously distorted and insulting non-interpretation of my poem.”

Years later, thinking about the furore around this poem, Baraka could say wryly, “Poetry is underrated. So when they got rid of the poet laureate thing, I wrote a letter saying ‘This is progress. In the old days, they could lock me up. Now they just take away my title.’ ”

In this poem, echoing the call and response style of the black church, as well having something of a reach-back again to the wild, apocalyptic language and style of Beat poets like Ginsberg and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Baraka had asked, “Who knew the World Trade Center was gonna get bombed,” and then implied an answer, writing, “Who told 4,000 Israeli workers at the Twin Towers to stay home that day?"

Baraka’s influence reached well beyond American literature and African-Americans, of course. South African writers like the then-exiled Keorapetse Kgositsile idolised him, and dramatist and director James Ngcobo said of him, Baraka’s literary footprints were immense and his work inspired (and still inspires) succeeding generations of writers “to weave words together.”

Years and years ago, when this writer first came to South Africa in the early 1970s, we found that although local writer-activists couldn’t put Amiri Baraka’s actual works on stage, in little out-of-the-way spaces, these young, angry black playwrights were putting on experimental work that seemed to draw their inspirations from Baraka’s explosive energy. Even now, one theatre piece still lingers in the mind. It had a text that was disarmingly simple in its straightforwardness. The cast, sitting on chairs on stage, simply repeated, with different voices, emphases and stresses: “When the revolution comes; WHEN the revolution comes; when the REVOLUTION comes; when the revolution COMES!” in an increasingly angry yet tantric repetition throughout the evening.

And, of course, Dutchman, Baraka’s early masterpiece, continues to live on, fully half a century after its premiere. In a 2007 review of a revival, The New York Times called it the “singular cultural emblem” of the black separatist movement in the United States. Only a few months ago, yet another production took place in New York City, this time in the steamy, overheated, claustrophobic confines of a public bathhouse!

A quick effort at tracking other productions within the past several years calls up yet others on stage across the US - and even one here in Johannesburg. This local production was part of a festival showcasing the work of young female directors and it was directed by actress/director Lindiwe Matshikiza at the Market Theatre.

The Miami Herald’s theatre critic could write of another recent production that “Baraka’s pointedly provocative, still-controversial one-act has been revived at Liberty City’s African Heritage Cultural Arts Center by the African-American Performing Arts Community Theatre. Though written in 1964, Dutchman has lost none of its sting since its debut almost 50 years ago at Off-Broadway’s Cherry Lane Theatre. This play is the opposite of the safe-bet, crowd-pleasing fare that so many nervous South Florida theater producers choose.”

And a review of a revival at the Cherry Lane Theatre, itself, said, “It's pretty simple really. On a subway, a boy meets a girl. He is black, she white. They flirt and argue, then flirt and argue some more. Eventually, one of them gets off the train, and they go their separate ways. Or, to be precise, one of them gets off the train and the other is carried off, stone dead, the going of separate ways being the main thrust of the thing. That is Leroi Jones' Dutchman, and the play has been poetically beguiling, politically challenging and generally shocking audiences into paying attention to the largely unspoken passions and shameful destructiveness built into American race relations since its first performance in 1964.”

Reviewing the newest production, this time actually inside that Manhattan bathhouse, Randy Kennedy could write in the New York Times that, “Mr. Baraka’s incendiary allegory about race and assimilation, the play will undoubtedly be no easier to watch than it was almost five decades ago. In part this will be because, for the first time, the play will have the Stygian setting its temperament seems to demand. And viewers — who will have to get a locker and shed their clothes and walk around in the same thin brownish-purple tunics that many bathgoers wear — will be crowded up against and sweating alongside the actors for about an hour, with precious little fourth-wall separation from the play’s mounting ferocity. (Hilton Als, in The New Yorker, once wrote that reading Dutchman is ‘like watching an expert butcher at his bloody chopping block.’)”

This clearly ain’t pretty, but it surely demonstrates the extraordinary staying power of Jones/Baraka’s early masterpiece, a work that audiences will undoubtedly be watching for years to come – horrified at what is unfolding, yet unable to look away – in contemplating the state of American race relations – and Amiri Baraka’s extraordinary optic on this.

Watch: Somebody Blew Up America

Somebody Blew Up America, by Amiri Baraka (full text)

They say its some terrorist, some barbaric A Rab, in Afghanistan

It wasn’t our American terrorists It wasn’t the Klan or the Skin heads

Or the them that blows up nigger Churches, or reincarnates us on

Death Row It wasn’t Trent Lott Or David Duke or Giuliani Or Schundler,

Helms retiring

It wasn’t The gonorrhea in costume The white sheet diseases That have

murdered black people Terrorized reason and sanity Most of humanity,

as they pleases

They say (who say?) Who do the saying Who is them paying Who tell the lies

Who in disguise Who had the slaves Who got the bux out the Bucks

Who got fat from plantations Who genocided Indians Tried to waste the

Black nation

Who live on Wall Street The first plantation Who cut your nuts off

Who rape your ma Who lynched your pa

Who got the tar, who got the feathers Who had the match, who set the fires

Who killed and hired Who say they God & still be the Devil

Who the biggest only Who the most goodest Who do Jesus resemble

Who created everything Who the smartest Who the greatest Who the

richest Who say you ugly and they the goodlookingest

Who define art Who define science

Who made the bombs Who made the guns

Who bought the slaves, who sold them

Who called you them names Who say Dahmer wasn’t insane

Who? Who? Who?

Who stole Puerto Rico Who stole the Indies, the Philipines,

Manhattan Australia & The Hebrides Who forced opium on the Chinese

Who own them buildings Who got the money Who think you funny

Who locked you up Who own the papers

Who owned the slave ship Who run the army

Who the fake president Who the ruler Who the banker

Who? Who? Who?

Who own the mine Who twist your mind Who got bread Who need

peace Who you think need war

Who own the oil Who do no toil Who own the soil Who is not a nigger

Who is so great ain’t nobody bigger

Who own this city

Who own the air Who own the water

Who own your crib Who rob and steal and cheat and murder and make

lies the truth Who call you uncouth

Who live in the biggest house Who do the biggest crime Who go on

vacation anytime

Who killed the most niggers Who killed the most Jews Who killed the

most Italians Who killed the most Irish Who killed the most Africans

Who killed the most Japanese Who killed the most Latinos

Who? Who? Who?

Who own the ocean

Who own the airplanes Who own the malls Who own television

Who own radio

Who own what ain’t even known to be owned Who own the owners

that ain’t the real owners

Who own the suburbs Who suck the cities Who make the laws

Who made Bush president Who believe the confederate flag need to

be flying Who talk about democracy and be lying

Who the Beast in Revelations Who 666 Who know who decide Jesus

get crucified

Who the Devil on the real side Who got rich from Armenian genocide

Who the biggest terrorist Who change the bible Who killed the most

people Who do the most evil Who don’t worry about survival

Who have the colonies Who stole the most land Who rule the world

Who say they good but only do evil Who the biggest executioner

Who? Who? Who?

Who own the oil Who want more oil Who told you what you think that

later you find out a lie

Who? Who? Who?

Who found Bin Laden, maybe they Satan Who pay the CIA, Who knew

the bomb was gonna blow Who know why the terrorists Learned to fly

in Florida, San Diego

Who know why Five Israelis was filming the explosion And cracking they

sides at the notion

Who need fossil fuel when the sun ain’t goin’ nowhere

Who make the credit cards Who get the biggest tax cut Who walked out

of the Conference Against Racism Who killed Malcolm, Kennedy & his

Brother Who killed Dr King, Who would want such a thing? Are the

linked to the murder of Lincoln?

Who invaded Grenada Who made money from apartheid Who keep the

Irish a colony Who overthrow Chile and Nicaragua later

Who killed David Sibeko, Chris Hani, the same ones who killed Biko,

Cabral, Neruda, Allende, Che Guevara, Sandino,

Who killed Kabila, the ones who wasted Lumumba, Mondlane, Betty

Shabazz, Die, Princess Di, Ralph Featherstone, Little Bobby

Who locked up Mandela, Dhoruba, Geronimo, Assata, Mumia, Garvey,

Dashiell Hammett, Alphaeus Hutton

Who killed Huey Newton, Fred Hampton, Medgar Evers, Mikey Smith,

Walter Rodney, Was it the ones who tried to poison Fidel Who tried to

keep the Vietnamese Oppressed

Who put a price on Lenin’s head

Who put the Jews in ovens, and who helped them do it Who said

“America First” and ok’d the yellow stars

Who killed Rosa Luxembourg, Liebneckt Who murdered the

Rosenbergs And all the good people iced, tortured, assassinated,

vanished

Who got rich from Algeria, Libya, Haiti, Iran, Iraq, Saudi, Kuwait,

Lebanon, Syria, Egypt, Jordan, Palestine,

Who cut off peoples hands in the Congo Who invented Aids Who put

the germs In the Indians’ blankets Who thought up “The Trail of Tears”

Who blew up the Maine & started the Spanish American War Who got

Sharon back in Power Who backed Batista, Hitler, Bilbo, Chiang kai Chek

Who decided Affirmative Action had to go Reconstruction, The New

Deal, The New Frontier, The Great Society,

Who do Tom Ass Clarence Work for Who doo doo come out the Colon’s

mouth Who know what kind of Skeeza is a Condoleeza Who pay Connelly

to be a wooden negro Who give Genius Awards to Homo Locus Subsidere

Who overthrew Nkrumah, Bishop, Who poison Robeson, who try to put

DuBois in Jail Who frame Rap Jamil al Amin, Who frame the Rosenbergs,

Garvey, The Scottsboro Boys, The Hollywood Ten

Who set the Reichstag Fire

Who knew the World Trade Center was gonna get bombed Who told 4000

Israeli workers at the Twin Towers To stay home that day Why did Sharon

stay away?

Who? Who? Who?

Explosion of Owl the newspaper say The devil face cd be seen

Who make money from war Who make dough from fear and lies Who want

the world like it is Who want the world to be ruled by imperialism and

national oppression and terror violence, and hunger and poverty.

Who is the ruler of Hell? Who is the most powerful

Who you know ever Seen God?

But everybody seen The Devil

Like an Owl exploding In your life in your brain in your self Like an Owl who

know the devil All night, all day if you listen, Like an Owl Exploding in fire.

We hear the questions rise In terrible flame like the whistle of a crazy dog

Like the acid vomit of the fire of Hell Who and Who and WHO who who

Whoooo and Whooooooooooooooooooooo! DM

Read more:

Amiri Baraka’s First Family at the New Yorker;

Dutchman’ remains a stinging political allegory at the Miami Herald;

Bruce Grund, director of "Dutchman," talks about the play in the subway car where it will be performed in the Daily Freeman;

Stage Review: 'Dutchman,' Cherry Lane Theatre, New York at the Post-Gazette;

Activist poet-playwright Amiri Baraka dies at 79 at the Miami Herald;

“Dutchman” – full text at the website of Arkansas Tech University;

Amiri Baraka, Polarizing Poet and Playwright, Dies at 79, at the New York Times;

Amiri Baraka (1934-2014): Poet-Playwright-Activist Who Shaped Revolutionary Politics, Black Culture at Democracy Now;

Poet Amiri Baraka dies, aged 79, at the BBC;

Amiri Baraka, black poet condemned as anti-Semitic, dies at the Jerusalem Post;

Searching for LeRoi Jones, Finding Amiri Baraka at The Root;

The Color of Politics - A mayor of the post-racial generation at the New Yorker;

Remembering Amiri Baraka (1934-2014) at the New York School Poets;

A Play That’s Sure to Make You Sweat at the New York Times.

Photo: Amiri Baraka (Creative Commons)