Maverick Life

28UP: Compelling documentary, compulsory viewing for politicians

The British TV series Up, which selected a group of children and filmed an update on their lives every seven years, is hailed as one of the greatest documentary projects of all time. South Africa is one of the countries which has its own spin-off, documenting the growth to adulthood of 18 children from vastly diverse backgrounds ever since they were seven years old in 1992. This year they are 28, and the fourth documentary installment of their lives – 28Up – will be screened in January. REBECCA DAVIS got a sneak preview of a fascinating project that deserves to be vastly better known.

The Jesuits have a saying: “Give me a child until he is seven and I will show you the man”. It expresses the idea that the early years of childhood are crucial predictors of what kind of adult a person will develop into, and this is the structuring concept of the British TV series Up. In the UK, director Michael Apted has been following the lives of a cross-section of British children since 1964, tracking them down every seven years to chart the changes and developments in their lives. The participants are now 56 years old, and 56Up premiered in the UK last year.

American film critic Roger Ebert, arguably the most influential film critic in the world up until his death in April this year, called the series “an inspired, even noble, use of the film medium”. The British documentaries have been rapturously received, with its participants frequently recognised in public, but the South African incarnation has received far less attention. This is manifestly unjust, because it is superb: beautifully, sensitively shot by award-winning Yizo Yizo director Angus Gibson. It also represents a fascinating opportunity to track social change – and the opportunity for social mobility – in South Africa over the past 28 years.

In some regards the South African 7Up, filmed when the 18 children were seven in 1992, is the best of the four installments produced to date. This is because, unexpectedly, children turn out to make wonderful documentary subjects, as they haven’t yet learned to be guarded in their responses (if you can overlook a slight ethical edginess around this). If you sit well-chosen seven-year-olds down and ask them questions like “What is the best thing that has ever happened to you?”, 7Up reveals that the results can be supremely entertaining: funny, heartbreaking and strangely insightful by turns.

1992 South Africa was a land in flux, with racial integration in schools beginning to happen for the first time. One of the most remarkable seven year-olds filmed for the documentary was Lunga, a black boy from a township near Durban who had managed to learn flawless English with a comical American drawl from many hours spent watching TV. As a result, Lunga was able to attend a predominantly white primary school in Durban. On camera, the precocious Lunga described his fear that he would be the only black child in his class, and then announced his desire to marry a white girl. “When I first got there I hated [the white kids],” he said. “Now I like them. They’re nice.”

Seven-year old Thembisile, who lived in Soweto with her grandmother, exuded sadness. She hated the township, she said, and she had clearly internalised a terrifying sense of inferiority. “Black people are ugly and whites are beautiful,” she said softly. Frans, from Alexandra, wanted to live among white people so he could be rich. But lively Claudia, who lived in a coloured area of Johannesburg, said that she wouldn’t like to go to school with white kids. “Maybe they speak another language and you ask them for the rubber and they won’t know,” she explained.

On the other side of social divide, seven-year-old Willem, growing up on a farm in the Northern Transvaal, was prepared for the black children who would enter his previously all-white school in August 1992. They would only be there till first break, he said. Why? Because we’ll beat them up, he said with a grin.

Seven years later, a 14-year-old Willem was shamefaced: “I was stupid,” he said. His black classmates were “very good people”. It was, in fact, “nice” to have them in school. But for the black children, the picture wasn’t so rosy. When the filmmakers tracked down 14-year-old Lunga, he was in hospital, having been hit in the head by a beer bottle. In the course of a fight, he had been accused of thinking he was “better” than his township peers because he went to a white school.

Thembisile, meanwhile, was still stuck in the same hostel in Soweto. “White people live comfortably. Black people are always in need,” she said. Conditions for Frans, too, were unchanged; still in Alexandra, he slept on the floor at the foot of the bed in his mother and father’s bedroom.

What was clear by 14 was the extent to which tragedy would touch these kids’ lives. Several had already lost parents. Tsepho dreamed of growing up and earning enough money to erect a beautiful tombstone for his dead mother. Shane, little Claudia’s big pal, had lost his father to gang violence. Claudia lived in fear of rape and hijacking. Lunga expressed enthusiasm for the death penalty.

By 21Up, filmed in 2006, three of the children were already dead. By 28Up, a further participant had died: four of the original 18 dead before 30. In the UK series, by contrast, all participants are still alive at the age of 56. 21Up is the most depressing of the four parts. Thembisile is still in Soweto, and weeps on camera about her desperation to find a job. Her mother is the only person in her family permanently employed. “I told myself when I grew up I’d get a job and help her,” she sobs. “I can’t.”

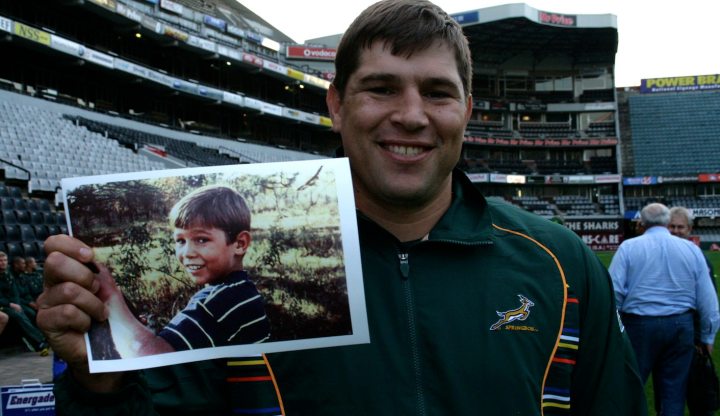

Frans is still sleeping on the floor. He hasn’t worked since he left school. He had prayed that an early talent for soccer would deliver him from a life of grim poverty, but it hasn’t worked out. A glimmer of hope is found in Claudia, who is studying science at Wits with the hope of becoming a doctor. The white children, by contrast, are mainly prospering – a factor which remains a constant across all four parts of the documentary. At 21, Willem is a University of Johannesburg student on a rugby scholarship. At 28, you may know him as the Springbok Willem Alberts, famed for his bone-crunching tackles.

One doesn’t want to give too much away about 28Up, filmed this year, except to say that the general picture for the participants is marginally more positive than at 21. But the overwhelming impression left by the series is one of depression and fatalism about the difficulty of escaping one’s initial social context in South Africa. If you were poor when you were seven years old in 1992, the show suggests, there is a high probability that you are still poor today. Possibly the major predictor of whether you will be able to advance socially is the quality of education you received – an unsurprising but frightening finding in a country where the education system is in turmoil.

But of course, some also comes down to the temperaments of the individuals involved. One has already had a short stint in prison. Others have bettered their situations through sheer tenacity. One of the reasons why the series makes for such utterly compelling viewing is that it provides not only a longitudinal study of South Africa’s shifting social landscape, but also fascinating insights into the effects of the passage of time on human character. It is heartbreaking to see that some of the children who were most dynamic and chatty at seven seem to have somehow lost a spark for life by 14.

What the series makes clear, too, is that South Africa can be an extraordinarily traumatic place to come of age if the social odds are not stacked in your favour. At the age of seven, most of the black kids had witnessed acts of horrifying violence first hand. Gugulethu’s Luyanda complained reasonably: “I hate getting shot at when I’ve done nothing wrong”. Shane claimed to have witnessed a shooting in the head. Linda, from rural Transkei, wanted to move to Cape Town because he didn’t like seeing “people get burnt”. There’s Lunga, aged seven, addressing the camera: “I think your police force is sick.”

The South African Up series should be compulsory viewing for politicians seeking to understand how, over the course of 28 years, the status quo for the people on the “ground floor” – as 21-year-old Frans put it – has in many cases remained materially unchanged. Director Gibson has said that they hope to continue making the series for as long as they can get funding, and as long as the participants remain willing. It is to be hoped that a terrestrial TV channel will be able to screen the full series eventually, because it really deserves as wide an audience as possible. If you have the chance to watch it, do. DM

28Up will be screened for the first time on Al Jazeera English on 3 January 2014. 7Up, 14Up and 21Up are being screened over the course of December.

Read more:

- Following the lives of Mandela’s children, on IOL

- 7Up South Africa, on Al Jazeera

Main Photo: One of the series’ participants is Willem Alberts, today a Springbok rugby player at 28.

Photo: Claudia and her friend Shane, 7 years old in 1992.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider