South Africa

What Winnie’s prison memoir reminds us about the Mandelas

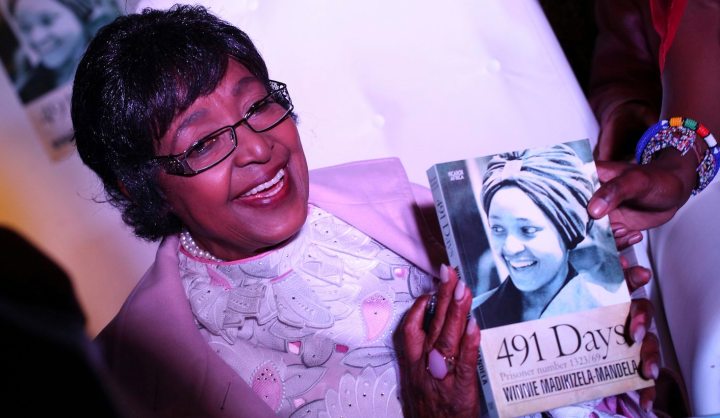

Winnie Madikizela-Mandela is now 77 years old, and a record kept by her while in detention in 1969 has recently been published. ‘491 Days’ is a collection not just of journal writings but also of letters between Nelson and Winnie Mandela when both were imprisoned simultaneously. It’s an interesting glimpse into the personality and history of a woman who continues to exert a certain fascination, and it makes it clear just how difficult it must have been in parts for the children growing up as Mandelas. By REBECCA DAVIS.

Just over a month ago, after the launch of her prison memoir 491 Days in Durban, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela gave an interview to the city’s Daily News. Talking about the increasing frequency of Marikana-type protests, she said: “God help us if one day the masses of this country rise against the state”.

From a woman who devoted the lion’s share of her life to struggling against the state, it’s quite a telling statement. There’s an implicit divide between “us” and “the masses” in it, and Winnie, perhaps disconcertingly, can no longer situate herself among “the masses” in good faith. It’s a seeming acknowledgement that new elites replaced old elites in the political system, and Winnie, for all her radicalism, is now one of them.

Winnie occupies a curious place in both the ANC and the popular understanding. Her fortunes have fluctuated between Polokwane and Mangaung, but she has held on to an NEC position and a seat in Parliament despite her notoriously bad attendance record. She is unafraid to make her thoughts known on what she views as the ANC’s current problems. In the same Daily News interview, she said that she could not “pretend that it is all well within the ranks of the ANC”, and that “today it is all about self-enrichment”.

She has also been outspoken in her belief that it was a mistake to expel former Youth League leader Julius Malema, and spoke in his favour at his internal disciplinary hearing. “I said, ‘If you have a child who is misbehaving, do you then close your door and tell your child to get out and see for himself out there in the world, cruel world where the child is likely to meet worse?’ she asked.

This kind of vocal doubt-casting on the decisions of top leadership, together with her woeful track-record in Parliamentary attendance, might see the end of a lesser cadre. But Winnie has always been something of a law unto herself. More importantly, she reportedly still commands broad, adulatory grass-roots support from South Africans willing to overlook the fraud conviction and the alleged involvement in the 1988 murder of Stompie Moeketsi in recognition of her vast personal sacrifice for the country’s freedom.

Here’s a few things that 491 Days reminds us about the “Mother of the Nation” and her family.

Growing up as Zindzi and Zenani Mandela can’t have been easy.

When Winnie Mandela was arrested, at 2.30 am on May 12, 1969, they were eight and 10 years old and already missing a father. They howled in fear as their mother was dragged away. Winnie did not know what had happened to them, or where they had been taken, for a month. “When I was in detention for all those months, my two children nearly died,” Winnie writes in the book’s epilogue. “When I came out they were so lean; they had had such a hard time. They were covered in sores, malnutrition sores. And they wonder why I am like I am. And they have a nerve to say, ‘Oh, Madiba is such a peaceful person, you know. We wonder why he had a wife who is so violent?’”

Winnie was never afraid to stand up for her rights.

There are numerous examples in her journal of Madikizela-Mandela challenging the authority of prison officials. When one comes to tell her, early on in her imprisonment, that they will decide when they feel like charging her with an offence, she blows up. “I screamed back and said who is he to tell me that. I asked if he had been promoted to the post of attorney general and that I thought he was a warrant officer, a rank he held before I was born.” For this insubordination she was deprived of all meals for a day.

She suffered many health difficulties in prison.

Blackouts, panic attacks, abnormal bleeding, bronchitis, anaemia, a heart condition. She received heart treatment, anti-depressants, injections for the bleeding. At one stage she expresses fear that she may be becoming addicted to the drugs. Some of her physical conditions were clearly the result of acute psychological stress. A psychiatric interview, with a ‘Dr Morgan’, was arranged. “Do you hear God’s voice sometimes telling you to lead your people?” Winnie was asked. “Would you ask Vorster’s wife the same question if the situation was reversed?” she shot back.

The toll her imprisonment took on her family was immense.

“I discovered I spoke aloud when I thought of my children and literally held conversations with them,” she wrote within the first two weeks of her detention. “I cried almost hysterically when I recalled their screams on the night of my arrest. I just cannot get this out of my mind up to date.” She was angered that letters written by Nelson Mandela to his children were never delivered, and saw in it a deliberate attempt to break down family relations. “It is not enough that we are both in prison and our children deprived of both of us,” she wrote. “It was enough of a blow to them to be without a father and all the struggle I’ve gone through trying to maintain them without employment.”

Her childhood was hard.

Madikizela-Mandela was nine when her mother died. In prison. “I can hardly remember her but I longed for her.” Her father was the local school’s principal, and Winnie was entrusted with washing his one school outfit overnight, with the family’s income too drained by medical fees for her mother to allow for new clothes. “The secret childhood tears I shed when the school children teased me about my shabbily dressed father,” she recalled. “I remember how I cried as I was forced to leave school, put my baby brother on my back and go to look after cattle.”

In April 1970, while in solitary confinement, she seriously resolved to commit suicide.

Her journal is fascinating in this regard. Her justification was that her own contribution to the Struggle at that time was too small to count, but “my death would be a major contribution which would stir up world opinion and touch the conscience of those fellow South Africans who still have some conscience”. Having made the decision to martyr herself in this way, she describes feeling a strange happiness. “I enjoyed the bitter-sweetness of unjust suffering and was quite excited when I thought how dramatic my death would be.” In the end, what changed her mind was the news that she would be charged and brought to face trial soon.

She held strong opinions about ANC strategy.

Winnie believed that acts of sabotage were essential, but that they should be carried out on things that couldn’t be fixed or replaced easily. “Setting fire to the Afrikaner farmer’s mealie fields all over the country [would] achieve something better than blowing up telephone booths which would take five minutes to repair,” she wrote, recalling an earlier discussion.

She was subjected to a great deal of sexist vitriol.

“The bloody bitch has sucked the saliva of all the white Communists, look at her!” a Special Branch officer suggested in front of him. His partner added, to roars of laughter, “Winnie would [have] seduced the Pope if she wanted to use him politically.”

Nelson Mandela loved her deeply and admired her mind and idealism.

His letters to her were suffused with devotion and admiration. “One of my precious possessions here is the first letter you wrote me on Dec 20, 1962 shortly after my first conviction,” he wrote to her in June 1969. “During the last 6 ½ years I have read it over and over again and the sentiments it expresses are as golden and fresh now as the day I received it.” To his daughters he wrote, “Do you see now what a brave Mummy we have?” Mandela liked to sign off his letters with salutations like “a million kisses and tons and tons of love”. He urged his wife to keep strong: “You will again see the picturesque scenery of the land of Faku where your childhood was spent, and the kingdom of Ngubencguka where the ruins of your own kraal are to be found.”

She thought of her relationship with Mandela as inseparable from the political struggle.

In a letter written in July 1970, she wrote: “Twelve years ago…a trembling little girl of 23 stood next to you in a shabby little black veld church in Pondoland and said, ‘I do’… It was to you and all what you stand for. The one without the other would have been incomplete for me.” In marrying Mandela, she wrote, “I was marrying the struggle of my people”. Upon her release, she would muse to him: “There comes a time in life when history completely kills personal life”.

Nelson Mandela has a hearty appetite.

“It dawned on me that it will not be long before I become elder, the highest title which even ordinary men acquire by virtue of advanced age,” he wrote to Winnie in August of 1970. “Then it will be quite appropriate for me to purchase some measure of corpulence to bloat my dignity and give due weight to what I say.” Once, he recalls, he was invited to dinner at the home of a medical student and her husband. The couple watched as Mandela consumed meat dish after meat dish. “Bluntly she told me I would die of coronary thrombosis probably in my early forties,” he wrote. Mandela defended himself by claiming that such thrombosis was unknown among his forefathers. “She promptly produced a huge textbook out of which she read out emphatically and deliberately the relevant passage. It was a galling experience. I almost immediately felt a million pangs in the region of my heart.” DM

Photo: Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, ex-wife of former South African President Nelson Mandela, smiles during a celebratory event around the release of her book titled 491 Days in Johannesburg August 8, 2013. REUTERS/Siphiwe Sibeko

Become an Insider

Become an Insider