South Africa

Jackie Selebi parole: Where the truth lies

Our former National Police Commissioner and Head of Interpol, Jackie Selebi, might not have broken any of his parole conditions going out to buy the Sunday papers. Still, it is difficult not to be cynical about his miraculous escape from the jaws of death since his release on medical parole in 2012. And even more difficult not to be angry when a Baragwanath doctor was shown the door for wanting to play by the rules. By MARIANNE THAMM.

In February 2012, a Johannesburg nephrologist, Dr Trevor Gerntholtz, was summarily ordered to leave the kidney unit at Chris Hani Baragwanath hospital, where he had worked as a volunteer for six years.

Gerntholtz would take three days a week off from his private practice in Fourways to run a clinic at Chris Hani for 15 renal patients. He also ran another money-generating research project for 130 patients on a blood pressure and cholesterol drug trial.

Gerntholtz’s crime?

The young doctor had dared to speak out about the preferential treatment given by hospital officials to Jackie Selebi, who had been released on medical parole after spending 229 days of his 15-year-sentence on corruption charges in the Pretoria Central Prison Medical wing.

It all started in December 2011. Selebi, who appealed the 15-year sentence handed down by Judge Meyer Joffe in 2010, had collapsed in the lounge of his Waterkloof home after learning that he would indeed be required to spend time in the slammer.

But, like Schabir Shaik, President Jacob Zuma’s convicted “financial advisor”, Jackie Selebi would never see the inside of a prison cell. He was immediately taken to Pretoria Central Prison where his pillows were fluffed up in the hospital ward.

Prior to his release, Selebi, supervised by Steve Biko Academic Hospital senior registrar, Dr Anil Kurian, had been receiving three daily dialysis treatments.

Selebi’s condition apparently deteriorated rapidly until June 2012 when a Correctional Services parole board granted the former commissioner his freedom (with strict conditions).

The grounds given for Selebi’s early release were that he was suffering from “a medical condition which is terminal, chronic, progressive and has deteriorated or reached an irreversible state.”

At the time, Minister of Correctional Services, Sibusiso Ndebele, claimed “the department has limited capacity to provide palliative care needed by some offenders”.

Selebi, we were led to believe, had only a few months left to live. And while Selebi might have been, in Judge Joffe’s words, “an embarrassment to the office [he] occupied” it seemed heartless not to release the old man so that he could die surrounded by his family (a privilege not afforded many other ordinary prisoners).

After Selebi’s release, Steve Biko Hospital’s chief executive, Dr Ernest Kenosi, reportedly said that the former commissioner would, in future, have to pay for his own medical costs “just like any other patient.”

It was shortly afterwards that Selebi visited the renal unit at Chris Hani Baragwanath for life-saving dialysis treatment at taxpayers’ expense – around R25,000 a month.

Photo: Dr Trevor Gerntholtz, volunteer nephrologist who was dismissed from Chris Hani Baragwanath. Picture Kevin Sutherland for The Times.

Dr Gerntholtz had been riled, he explained, because Selebi, as a 61-year-old, diabetic prisoner did not qualify for the treatment. Patients who are older than 50 and diabetic are not eligible for dialysis at state hospitals and neither are prisoners.

“There are strict national criteria when it comes to patients who require dialysis and these were simply ignored when it came to Selebi. I said it was unfair. There were 25-year-old patients who needed treatment,” said Gerntholtz.

Gerntholtz voiced his displeasure in a subsequent radio interview with 702 during which he pointed out that around 30,000 patients in South Africa required dialysis and that only 5,000 were being treated because of capacity constraints.

Bumping a politically connected prisoner up the waiting list at the expense of ordinary, younger, poorer patients who were desperate for treatment was blatantly unethical. Gerntholtz, who was no longer on the Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital payroll (he had worked there from 2003 to 2005), had every right to express his displeasure.

But instead of being lauded for his civic-mindedness, Chris Hani Baragwanath CEO, Johanna More, and senior clinical executive, Dr Khairul Mustafa, called Gerntholtz in and informed him that his comments on air had been “hurtful about a sensitive issue”, that he was no longer welcome at the institution and that he was to leave immediately.

And there we have it.

The incident with Dr Gerntholtz is indicative of the attitude of many towards Jackie Selebi. Faced with evidence that Selebi was corrupt and that he had been bribed by drug-trafficker Glenn Agliotti, people who should have known better continued to blindly support him.

In 2006, when it became clear that alarming allegations that Selebi was involved with organised crime syndicates needed to be taken seriously, former president Thabo Mbeki confidently announced to the citizenry, “I have the greatest confidence in National Commissioner Selebi”.

In June 2008, three months after Selebi had shuffled into the dock of the Randsburg Magistrate’s court, President Thabo Mbeki renewed his old friend’s contract as the National Commissioner for another 12 months.

While being chauffeured to a nearby mall to buy the newspapers in no way compares to Schabir Shaik’s miraculous resurrection from deathbed to golf course, the public can hardly be blamed for being cynical.

While the Shaik and Selebi cases are vastly different (in fact no-one doubts that Selebi is indeed a sick man) the fact that his early release is viewed with suspicion is indicative of the erosion of public confidence and underscores the belief that the politically connected are protected and receive preferential treatment.

Responding to the sighting of Selebi at a the Monument Park shopping mall on Sunday, Department of Correctional Services Chief Deputy Commissioner, Teboho Mokoena, said that Selebi had not violated any conditions of his parole.

“He is allowed to be outside between 9am and 5pm at the time he was seen. He was not partying or dancing. He was just going out to get the papers,” said Mokoena.

Some of the other conditions of Selebi’s parole are that his is not allowed to move outside the Pretoria Magisterial District or drink alcohol.

Mokoena added that the Department had made in clear in 2010 that it would not foot Selebi’s medical bills and that these would, upon his release, be for Selebi’s private account.

In June 2012 the Minister of Police, Nathi Mthethwa said that Selebi was receiving “normal retirement benefits from the Government Pension Administration Agency” and that he was “receiving the normal Polmed benefits applicable to a pensioner”.

It seems that Mthethwa’s claim is in contravention of the South African Police Act, which prevents any member who has been convicted of an offence and given a jail sentence without the option of a fine (as is the case with Selebi) from receiving these benefits.

Section 36(1) of the Act stipulates that “a member who is convicted of an offence and is sentenced to a term of imprisonment without the option of a fine, shall be deemed to have been discharged from the Service with effect from the date following the date of such sentence: Provided that, if such term of imprisonment is wholly suspended, the member concerned shall not be deemed to have been so discharged.”

In the meantime, Paul O’Sullivan, the investigator who was instrumental in exposing Selebi’s criminal activities, has sued the commissioner as well as his former employer ACSA for R40-million. On top of it, Selebi’s estimated R17.4 million legal bill, footed by taxpayers, has yet to be recovered. Selebi’s lawyer has claimed that the former commissioner does not have enough money to pay back his debt to the state.

The Jackie Selebi corruption trial was one of the most shameful episodes in our young democracy. While many in the ruling party would have preferred to consign the issue to history, the fallout from the Selebi era will continue for many years to come. The former commissioner’s sudden return to better health and public view, so close to the 2014 elections, is just another reminder that politics trump all else today and that people of South Africa are still far from being equal.

That Dr Gerntholtz is no longer allowed to help Baragwanath’s renal patients after telling truth to power is not the first and will not be the last proof of that sad reality. DM

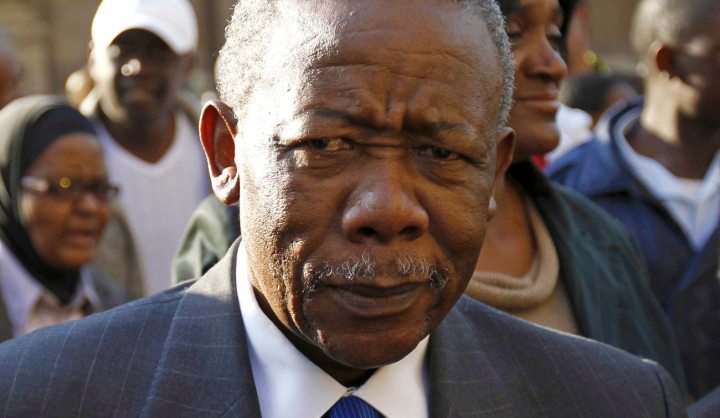

Main Photo: Jackie Selebi, the former head of South Africa’s police force, leaves after his appearance at Johannesburg High Court August 2, 2010. REUTERS/Siphiwe Sibeko

Become an Insider

Become an Insider