South Africa

The UDF at 30: An organisation that shook Apartheid’s foundation

Thirty years ago this week, the United Democratic Front – the UDF – became a critical part of the South African political landscape, until its formal dissolution eight years later. During that period, the UDF demonstrated that even in the most astonishingly difficult circumstances, a broad, diverse coalition of groups and individuals could be held together – despite institutional differences, arrests, banning orders and differences in ideology - to put sustained, ultimately successful pressure on an odious regime. And even if the UDF was not able to make the entire country totally ungovernable, they did succeed in making it impossible for the old order to continue. In doing this they cleared the decks for South Africa’s new non-racial order. J. BROOKS SPECTOR takes an appreciative look back at the UDF at how it did and what it all meant.

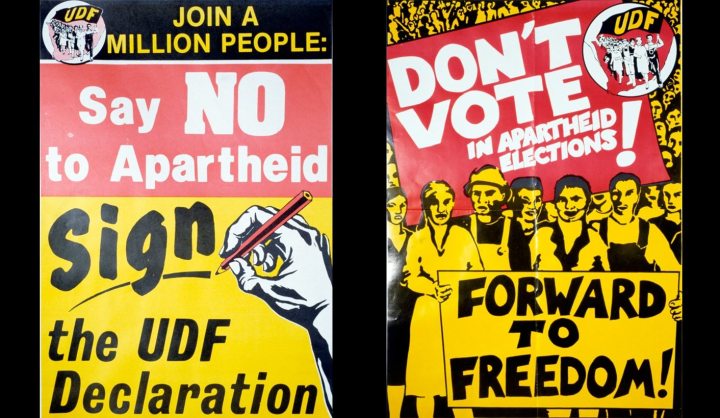

Right off the bat, it must be said that the UDF and all its affiliated organisations had great posters and t-shirts. This certainly should not be seen as a put down. Instead, it became an innovative tool for the UDF’s success and those of its many affiliates and associates. Posters, banners and T-shirts could be produced quickly and cheaply and they became a force multiplier – publicising a cause, an event, a campaign or a new slogan on walls and street corners, and on the torsos of many thousands. A vivid image could be passed from one silkscreen shop to the next to be reproduced, sometimes advancing the story line with each new iteration. As pre-Internet, pre-social media artefacts, they became viral campaigns even before that particular term of art had been named.

On this precise point, the South African History Archive explains that once the UDF was created in 1983 it brought “many grassroots organisations under one banner. Some organisations consisted of cultural workers who established screen-printing resource centres. These were aimed at providing training, while serving the needs of all the UDF affiliates. In Johannesburg, the Screen Training Project (STP) was established while the Community Arts Project (CAP) was based in Cape Town. These projects were responsible for the production of thousands of posters, T-shirts, badges and banners.”

Eventually, of course, from early 1990 onward, one could go to what was informally dubbed the UDF shirt store in downtown Johannesburg to shop for one’s personal choice of cause T-shirts from a wide, constantly changing selection – so as to demonstrate solidarity with a particularly favoured particular cause. Somewhere in storage boxes in the writer’s home there is still a cache of some of those very shirts, saved for the day when they would be given to a museum – some distant time into the future. And over the past few years there have been a number of exhibitions of UDF posters and other cause ephemera, designed to acknowledge the nostalgia and magic for a past era where the causes were simpler and purer than anything true now.

And how did the UDF happen? Following the crackdown on the Soweto student’s uprising in 1976, the late 1970s had become a period of increased repression. But in January 1983, Rev Allan Boesak called on South Africans to establish a “united front” of “churches, civic associations, trade unions, student organisations, and sports bodies” to fight Apartheid when he spoke at a meeting of the Transvaal Anti-SAIC (the SA Indian Council, a body connected to the national government office that managed segregated “Indian affairs”) Committee. The ensuing debate following his speech led to a big idea – the creation of a coalition of consciously non-racist organisations all across the country.

University of Cape Town academic and historian of the UDF, Jeremy Seekings, has written of this birth that “The UDF was born out of a concern to oppose the constitutional reforms proposed by the state with the goal of co-opting coloured and Indian South Africans into supporting an inadequately reformed version of Apartheid. Opposition to the continued exclusion of black African people combined with opposition to the unequal basis on which the Apartheid state proposed to incorporate coloured and Indian people into a pro-Apartheid coalition. The UDF’s leadership at national and regional levels included many activists from coloured and Indian neighbourhoods because of the central importance of campaigning in these areas.”

Over the next seven months, provincial-level UDF coalitions began to take shape. By the end of July a working group that included Albertina Sisulu, Mewa Ramgobin and Steve Tshwete had decided to launch this new national front on 20 August, a date deliberately picked to counter the government’s introduction of legislation in the whites-only parliament to establish the so-called tricameral parliament. This would be a new parliamentary system with new chambers to deal with Coloured and Indian “own affairs” – but with the continuation of the still-white chamber for pretty much everything else. The organisers agreed on a logo for this new thing, the UDF, and their first public slogan – “UDF Unites, Apartheid Divides”. Their next decision was that any group working with government structures, cooperating with the homeland state structures (the “bantustans”), or groups breaking the increasingly visible sport and cultural boycotts would not be allowed to join the new UDF.

And so on 20 August 1983, delegates from around the country formally constituted the UDF at a meeting in a hall in Mitchell’s Plain near Cape Town that was followed by the UDF’s first public rally, with about 10,000 people. At that organisational meeting, the very first speaker was Rev. Frank Chikane and then the keynoter came from Rev. Allan Boesak who spoke of how they would bring together a diversity of groups to fight for freedom. They drafted a task agenda that focused on building an organisation that would represent all parts of the population – in stark contrast with that derided tricameral parliament. The meeting had brought together delegates from 565 different organisations from the nascent body’s regions across the nation.

The impetus for the new UDF drew on the fertile ground of a growing hunger nationally for mass anti-Apartheid-directed organisations, as well as a growing political consciousness in many of South Africa’s townships and black neighbourhoods. In the hard years following the crushing of the Soweto students uprising, a growing number of South Africans had been covertly reading and discussing revolutionary-style literature, including banned ANC material, although many of those discussions also drew on black consciousness literature (including important works of black American fiction).

As the UDF came into shape, its campaigns went beyond opposition to the tricameral parliament and began to focus on the upcoming, planned elections for the so-called Black Local Authorities (BLAs) for the townships that had been designed as a sop to the African population in lieu of any participation in that tricameral parliament. The UDF called for a boycott of the elections and the resulting very low turnout bolstered UDF confidence and helped enhance its standing nationally. Meanwhile, the UDF returned its attention towards that tricameral parliament – first coming out against the whites-only referendum on the new body and then the referenda for Coloureds and Indians. Eventually they called for a non-racial referendum across the board and amidst the tension over the planned votes, the government eventually abandoned the idea of these two additional referenda. The UDF then launched its Million Signatures Campaign against Apartheid. Success was not foreordained – it could only collect a third of its intended total.

But by the middle of 1984, with more organisational experience under its belt, a now-emboldened UDF took the offensive against the actual elections for the Coloured and Indian houses of the new parliament. With increasingly effective activities, the UDF leadership also drew the growing attention of the government – leading to the usual arrests and detentions. Nevertheless, the voting percentages for the two houses of the tricameral parliament came in at only around 20% as a result of the calls by the UDF and other groups for people to boycott those elections.

Once the tricameral parliament opened its doors on 3 September 1984, protest demonstrations, school boycotts and stay-aways began in the Witwatersrand and Vaal Triangle regions, although they were initially fuelled by plans to raise municipal services fees rather than the tricameral parliament itself. In the end, these protests set off the longest sustained period of black resistance to white minority rule in South Africa’s history. At least initially, UDF was not involved in these new protests – it had been maintaining its focus on the tricameral parliament instead.

Nonetheless, the government decided the UDF was deeply involved. And by late October-early November, Transvaal UDF affiliates had come together to create a special stay-away committee. This pushed the national UDF leadership to reconsider the usefulness and impact of such mass movements as they began to move up the learning curve in how to build mass mobilisation campaigns. This time, perhaps as many as 800,000 people ultimately responded to the call to stay home. A now more emboldened UDF, together with the Federation of South African Trade Unions (a precursor to COSATU) called for a “Black Christmas” to mourn those who had died in the protests or were still in detention as a result of the protests that would have people forego buying luxuries or holding parties during the traditional 16-26 December period.

The struggles of the previous three years were putting the UDF into balancing the tension between its frequently expressed non-racialism and its increasing ties to protests rooted in the country’s African townships. Increasingly this happened as mass school boycotts and equally mass funerals became a large proportion of UDF activities. Not surprisingly, these circumstances also created tensions between the front’s student formations and other parts of the UDF alliance. (Such boycotts, with their slogan, “liberation before education” also nurtured a protest tradition that has contributed to the difficulties that continue to plague so many of South African schools.)

By 21 July 1985 the government had declared a State of Emergency in 36 magisterial districts in the Eastern Cape and what is now Gauteng – the first such declaration since 1960, giving the police broad powers to detain, impose curfews and control the media and, a few days later, even to control funerals. The UDF was now increasingly under pressure, many of its leaders imprisoned, its networks giving way. At this juncture, consumer boycotts became the mostly widely used means of civic revolt – both with UDF sanction and from other bodies. While such efforts were supposed to be non-violent protests, violence did occur as people were sometimes forced to participate – or else.

By 1986 many of the UDF leadership cadre were singled out for arrests as people like Popo Molefe, Terror Lekota and Moss Chikane were brought into detention until they ended up as defendants in the marathon treason trial in the town Delmas many kilometres from Pretoria or Johannesburg. Meanwhile, the UDF had to wrestle with an internal tension between supporters of mass organisation and mobilisation versus those who advocated still more vigorous forms of protest.

While all this was taking place in the Transvaal, on 28 August 1985, Rev. Allan Boesak had organised a march in the Western Cape from Athlone Stadium to Pollsmoor Prison, focusing on non-violent resistance to repression and detention. In the ensuing police efforts to break up the march, nearly 30 people were killed. This, in turn, set off growing violence and the police responded by shutting 500 Coloured schools in the area. At that point, the UDF and unions pushed for a two-day strike and the violence began spread to Natal as well. Beyond protests against the government, this also led to African violence and Indians and UDF/Inkatha clashes, despite UDF calls for non-racial protests.

Observing this unruly period, the SA History Archive notes, “By the end of 1985, the UDF still found the township revolts problematic and found itself in a difficult position. It recognised the increased anti-Apartheid action in the riots as positive, but was worried about the level of violence and the lack of organisation. The UDF itself was in a state of disarray as many of its leaders were detained, and Congress of South African Students (COSAS) was banned in August” as some 8,000 UDF leaders had been detained and most of the organisation’s national and regional leaders had either disappeared, been killed or simply fled South Africa. By this point, the UDF had evolved into an organisation that had acceded to the reality of growing militancy and power in the hands of the people rather than in the hands of the UDF’s leadership. In this new reality, by December 1985 the UDF would attempt to give some direction to the population’s resistance as it issued a call for a second Christmas-time consumer boycott.

Meanwhile, on the international front, in January 1986, UDF leaders first met ANC representatives in Stockholm, Sweden to clarify their relationship and to sort out a longer-term role for the UDF. The ANC had argued for parallel streams of a “people’s war” and negotiations, calling on the UDF to increase pressure inside the country in tandem with efforts by the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), as well as pressure from key groups of white South Africans.

In response to these discussions, the UDF made a more determined push to embrace the concept of “peoples’ power” and to build deeper organisational structures at local levels such as via street committees in the Eastern Cape and Gauteng townships. Once the first state of emergency had been lifted in 1986, however, those so-called “peoples’ courts” had taken charge of dispensing a kind of street justice in some places via a high level of violence and mob action. An Easter 1986 UDF conference in Durban attempted to deal with the unpredictability of this kind of ungovernability, urging instead that people take political control of their townships, their factories and their schools, despite the state’s near monopoly of lethal force. In this way, the UDF was attempting to move towards staking out a more proactive leadership of township protest as resistance patterns evolved.

As the protests grew and violence against regime collaborators also increased – including the use of necklacing – vigilante groups, especially in Natal and Kwa Zulu, but also in the Cape Town area during the Old Crossroads removals, grew in reaction to the UDF’s efforts as well. As UDF structures grew in strength, they began to employ regional organisers to coordinate media efforts, political education and financial accountability as they areas became additional key UDF objectives. By the end of 1986, the UDF could claim to have sustained the peoples’ revolt, unlike after 1976-7 or 1960-1. The UDF could point to their sustained pressure on the government, in spite of the military balance starkly in the government’s favour. The state was forced to rely increasingly on direct military power and then issued a new declaration of a national state of emergency on 12 June 1986.

Together with growing international isolation and the severe financial crisis of the period, despite the state of emergency, the on-going bannings and other forms of repression, it was becoming clear the power balance was slowly tipping away from the government. Increasing numbers of white South Africans were calling for an end of Apartheid (or avoiding the military service draft) as well. As a result, the UDF leadership felt it was the right time to work in a much more above-ground fashion, especially in alliance with an increasingly powerful COSATU as the loosely affiliated Mass Democratic Movement – and with their growing connections with an ANC that was still in exile. After some discord, the movement initiated a national protest on 6-8 June that was effectively a mass stay-away – and it garnered around 3 million participants – a vivid measure of the real power this opposition had gained in its confrontation with the government, despite the government’s efforts to suppress it.

The MDM claimed its boycotts of the municipal elections in 1988 marked another success for the power of mass mobilisation and that the newest state of emergency had not broken the power of the opposition – strengthened further after Mohammed Valli Moosa, Vusi Khanyile and Murphy Morobe escaped from detention (and initially hid in the US Consulate General in Johannesburg for weeks), although the severe sentences for those being tried in the Delmas Treason Trial became a setback. But by mid-1989, the concept of the MDM had taken hold, even if some black consciousness leaders continued to criticise it for its presumed elitism and democratic centralism. However, the strife between the UDF affiliates and Inkatha continued to grow worse in rural Natal and Kwa Zulu territories.

On the other hand, by the end of 1989, it was clear when the FW de Klerk government began to permit some MDM marches, change of some kind was in the air. The UDF/MDM organised two conferences to address the way forward, the “Conference for a Democratic Future” and “From opposing to governing: How ready is the opposition?” They drew a wide range of participants but these deliberations were suddenly overshadowed by the release of a number of high-profile prisoners like Govan Mbeki, then the unbanning of the ANC and other heretofore banned political parties, and then, astonishingly, the release of Nelson Mandela.

In effect, the UDF had won its main demands for a real movement towards a new order and a movement towards a constitutional assembly to draft a future non-racial, democratic, and unitary South Africa. But then, at the moment of their victory, an as UDF tried to rebuild its own structures, it now needed to address the challenges of defining its relationship with the now-returning ANC – especially as many of its most prominent and experienced leaders were being drawn into the repatriation and establishment of the ANC inside South Africa, instead of any further UDF campaigns or more mundane organisational issues.

And so, after much discussion, in March 1991, they decided the UDF would disband – and any subsequent reconstruction of its broad church of affiliates would now have to be left to new parties. Over the next five months, the UDF focused on winding up its affairs, sorting out its finances, retrenching employees, and distributing its tangible assets. They “turned out the lights” on 14 August 1991 after eight enormously eventful years. And amazingly, its unique history seems increasingly faint, subsumed into the broader narrative of the liberation movements and “The Struggle”.

American academic Gail Gerhart, reviewing two major treatments of the UDF’s unique history written by Jeremy Seekings and Dutch scholar Ineke van Kessel, wrote in “Foreign Affairs” over a decade ago, when the UDF’s memory was still relatively fresh for many, that the two authors had worked hard to “probe far below the surface of South Africa’s liberation struggle to expose the often messy and inconclusive underside of politics – the part outsiders rarely see and victors prefer to forget once they prevail.”

And Seekings, himself, has argued in his writings, “The most extraordinary thing about the national launch of the UDF, held in Mitchell’s Plain, was that it was attended by activists from all over the country, and the new organisation was national in ambit. For the younger generation of activists, this was an unprecedented event. Only older, veteran activists would have been able to recall similar events prior to the suppression of the 1960s. In interviews, activists recall that they met for the first time at the launch people from other parts of the country who, until then, had been mere names. In many cases, even quite senior members of ANC underground structures had not met each other. Thereafter, activists were linked into a national movement with countrywide networks.” What the UDF may also have done, in their efforts to render the Apartheid government inert and effectively incapable of action, was to be the crucial first step in forging a new national identity; an identity not solely rooted in race or class. And for that achievement, if for no other reason, the UDF should be remembered, honoured and feted for generations yet to come. DM

A basic chronology of the UDF

1983

- January, Alan Boesak calls for the formation of the UDF at a SAIC Committee (TASC) conference in Johannesburg; A commission appointed; steering committee set up.

- May, Transvaal and Natal regions launched

- July, Eastern Cape and Border committees set up

- August, National Launch of the UDF set up to coincide with the government’s introduction of the tricameral legislation in August.

- November/December, The UDF began to focus on the planned elections for the Black Local Authorities (BLAs) and other local government in the townships. The UDF called for a boycott of the elections, but the campaign was run mainly though affiliates and the UDF only played a coordinating role. The UDF interpreted low voter turnout as a victory.

1984

- January, UDF Border region launched The Million Signature campaign is launched

- April, West Coast UDF and Southern Cape region launched

- July, Anti-tricameral parliament campaign launched

- August, UDF leaders arrested six UDF Natal and Natal Indian Congress leaders sought refuge in British consulate

- September, Regime held elections for tricameral parliament amid massive boycott

- Vaal erupted over rent boycotts; four local authority councillors killed

- October, UDF and ECC held ‘Troops Out’ campaign

- November, UDF organised Transvaal stay-away to protest troops in townships

- December, UDF leaders charged with treason in Durban; formation of the Federation of Transvaal Women as a UDF affiliate

- UDF led Black Christmas campaign

1985

- January, Senator Edward Kennedy visited South Africa Jan

International Year of the Youth

- February, At a rally to celebrate Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s winning of the Nobel peace prize, Zindzi Mandela read Mandela’s response to the government’s offer to release detainees

- UDF offices raided countrywide; over 100 arrested; leaders charged together with previous six treason trialists in the Pietermaritzburg Treason Trial

- March, Langa, Uitenhage massacre

- April, Second UDF National General Council in Azaadville

- Popo Molefe and Terror Lekota detained

- June, Gaborone raid; Pebco Three went missing

- Together with 20 others, Molefe and Lekota charged with treason in the Delmas Treason Trial

- Matthew Goniwe, Fort Calata, Sicelo Mhlauli and Sparrow Mkhonto (the Cradock Four) found murdered

- 30th anniversary of the Freedom Charter

- July, Mass funeral for the Cradock Four

- State President PW Botha declared a State of Emergency in 36 magisterial districts; 136 UDF officials known to be detained

- August, Victoria Mxenge murdered

- Inkatha attacks intensified

- Cosas banned

- October, Communities engaged in consumer boycotts to protest black local authorities and national repression; UDF launched “Forward to People’s Power” campaign

- December, Cosatu launched

- National Education Crisis Committee (NECC) formed

1986

- January, Murphy Morobe detained; released March 7

- February, Six Day War in Alexandra

- Northern Transvaal region UDF launched

- March, State of Emergency lifted May 1986 UDF with Cosatu and other organisations organised national stay-away

- May, Campaign against public safety bill

- UDF ‘Call to Whites campaign

- June, National State of Emergency declared

- Murphy Morobe spoke on UDF under the State of Emergency

- UDF launched ‘Unban the ANC’ campaign

- August, White City, Soweto massacre

- October, UDF declared affected organisation

- Campaign for ‘National United Action’ (Cosatu, UDF, NECC, SACC)

- ‘Christmas against the Emergency’ campaign

- January, The theme for the UDF for 1987 was ‘Forward to People’s Power’

- Valli Moosa detained and released on April 12

- April, UDF Women’s Congress formed

- May, Cosatu headquarters bombed

- National action and protest

- Day of national protest against whites-only elections

- UDF National Working Committee 200 delegates from nine regions: STvl, NTvl, ETvl, ECape, WCape, NCape, Natal, OFS, Border; Anti-Bop campaign

- July, Sayco ‘Save the Patriots’ campaign

- August, Murphy Morobe and Valli Moosa detained (22 UDF NEC members in detention)

- ‘Friends of UDF’ launched

- Cosatu union National Union of Mineworkers held strike to demand living wage

- UDF adopted the Freedom Charter

- November, UDF called for boycott of black local authorities

- Govan Mbeki released

1988

- February, UDF and 16 organisations and 18 individuals restricted; Cosatu restricted from doing political work

- March, Day of action

- May, Cape Democrats launched

- June, ‘National peaceful action’ called by Cosatu supported by UDF and churches

- September, Security police bombed Khotso House, national headquarters of the UDF

- Murphy Morobe, Valli Moosa and Vusi Khanyile escaped from prison and took refuge at the US Consulate, Kine Centre, Johannesburg

- October, Anti-municipal elections campaign

1989

- February, MDM statement on Winnie Mandela

- May, David Webster assassinated

- August 31, Five days before the general election where only White South Africans could vote, South Africans all over the country organised a defiance campaign against the election. Various organisations from the Anti-Presidents Committee to students’ organisations, Trade Unions, United Democratic Front, and many others successfully organised protest action for this day, the day was labelled ‘Day of Rage’ by the Weekly Mail and Guardian newspaper. The police reacted by detaining at least 100 people, banning protest marches and all meetings organised by anti Apartheid organisations.

- September 1, A Defiance Campaign, similar to the 1952 Defiance Campaign, is launched by theUDF against banning, restrictions and segregation of hospitals and other public facilities.

- October, Walter Sisulu and other Rivonia trialists released, National Reception Committee formed

- December, Conference for a Democratic Future (CDF)

1990

- February, ANC and 72 other organisations unbanned; restriction on UDF lifted Nelson Mandela released

- March, UDF-Cosatu national women’s workshop

- May, First meeting between ANC and Apartheid government

- July, Week of ‘National Mass Action’ against violence in Natal

- August, Bantustan conference

1991

- Dissolution of UDF

*******************************

Read more:

- Online exhibition marks UDF anniversary at the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory website

- Legacies and Meanings of the United Democratic Front (UDF) Period for Contemporary South Africa by Raymond Suttner in “From National Liberation to Democratic Renaissance in Southern Africa” at the Codesria.org website

- Celebrating the UDF by Jeremy Seekings at Reconciliation Barometer website

- Jeremy Seekings’ “The UDF: A History of the United Democratic Front in South Africa,” Reviewed by Ineke van Kessel at H-Net.org’s website

- UDF Thirty Years at the SA History Archive

- The UDF Period and its Meaning for Contemporary South Africa by Raymond Suttner in the Journal of Southern African Studies, at Abahlali.org

- The UDF: A History of the United Democratic Front in South Africa, 1983-1991; Beyond Our Wildest Dreams: The United Democratic Front and the Transformation of South Africa at Foreign Affairs

- The birth of the movement, August 1983 at SA History.org

- UDF has served its purpose – Manuel in the New Age

Become an Insider

Become an Insider