South Africa

The Marikana Commission, and skewed access to justice

As the Marikana Commission of Inquiry lingers on, the anger that many South Africans felt towards the South African police and government has been diffused by the spectacle of the Commission itself. But as many South Africans now react with more complacency to Marikana, the Commission itself is a telling reminder of the problems associated with the access to justice in South Africa. By KHADIJA PATEL.

Blink (or take a detour through Pretoria thanks to an over-eager GPS) and you may have missed it. The Commission of Inquiry into the Marikana massacre reconvened in Pretoria on Wednesday morning but was adjourned within an hour. The commission will reconvene next Monday, more than one year after police gunned down 34 miners near the Lonmin platinum mine in the North West province.

President Zuma on Wednesday described the Marikana massacre as a “tragic and sad loss of life”.

“I appointed a Judicial Commission of Inquiry into the incident led by Judge Ian Farlam,” Zuma said. “We respect the Commission and will not pre-empt its findings or interfere with its work by speculating on what happened on that day or apportioning blame.”

On Planet Reality, however, the frequent postponements the Commission has suffered have led some to question the Commission’s credibility.

Bongumusa Trevor Sibiya, from the Legal Resource Centre, acting on behalf of the Ledingoae family (Kutlwano Ledingoane died at Marikana) says in an affidavit quoted by the Mail & Guardian:

“The Commission is unlikely to be viewed as credible if it is tainted by unfairness. Manifest unfairness arises in the eyes of the public when one side to the dispute, namely the police, is lavished with financial support and personnel, while the other side is denied even the most basic support to be adequately represented.”

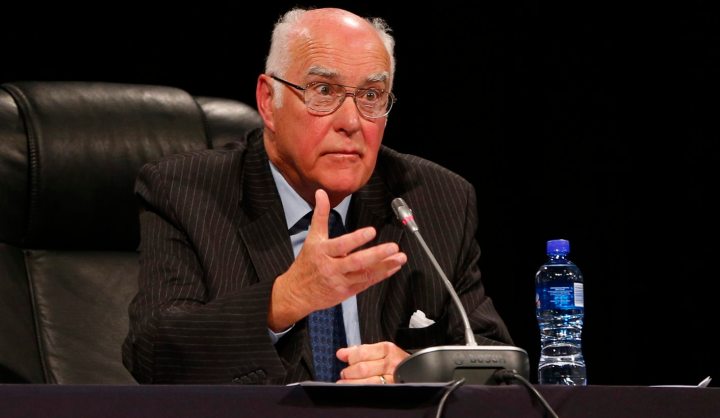

At the Pretoria municipal office, where the Commission is now based, Ian Farlam sought to allay these concerns on Wednesday.

“The members of the Commission are very conscious of the need to reach a conclusion without undue delay,” Farlam said.

He noted that the Commission has held 114 sessions to date and has heard submissions and collected evidence “which run to more than 12,000 pages of transcript”.

“We have heard extensive opening statements by interested parties; we have conducted inspections in loco; we have viewed video recordings of some of the events of that week in August 2012; we have examined a very large number of documents which now form part of the evidence; and we have heard the evidence of a large number of witnesses who have been examined and cross-examined,” Farlam said.

The lack of funding for the lawyers representing miners wounded and arrested during the Marikana unrest has significantly delayed the progress of the Commission.

As it stands, the donor said to be interested in funding the legal representation for the injured and arrested miners has not yet taken a decision on whether to fund the legal team. Farlam, however, is confident that a decision will be reached by Monday when the Commission reconvenes.

In the meanwhile, the setbacks the Marikana Commission has suffered reflect an unflattering reality of the South African judicial system. Many of the challenges the Commission has had to negotiate in its aim to understand how exactly 34 South Africans were shot dead by the South African Police Services last August, are not unique to this Commission of Inquiry.

When Farlam explained the reasons for the Commission’s many delays on Wednesday, he listed two impediments to speedy progress. He listed firstly the number of parties participating in the Commission: “With so many witnesses and so many cross-examiners, it is inevitable that progress has not been rapid,” he said.

That impediment may be unique to the Marikana Commission, but many of these problems are the everyday experience of South African courts by ordinary South Africans; this Commission merely amplifies those challenges.

Negotiating the barrier of language during the Commission’s proceedings has also delayed progress.

“It is important that as many as possible of those who wish to do so, should be able to hear and understand the evidence; this is particularly the case for the families and loved ones of the deceased, namely the miners, the Lonmin employees and the members of the Police Service, all of whom died during the period from 12 to 16 August 2012,” Farlam said.

He added that while the process of interpretation has slowed down the progress of the Commission, “it has, however, been necessary, in order to ensure the inclusiveness of the process”.

That problem appears to have been solved now.

“Some time ago, the Commission attempted to address this problem by requesting the Department to arrange a simultaneous translation service. We were advised that this could not be done, for reasons of cost,” Farlam said. “The Commission has renewed this request, and I am pleased to report that the Department has now made the necessary facilities available.”

President Zuma himself acknowledged, when he addressed a conference on access to justice in 2011, these shortcomings, including those of language, of the South African judicial system.

“The other side of the coin is the difficulties for the recipients of justice, especially the poor. Their situation is more desperate because unlike judicial officers, they are powerless and usually cannot solve the conditions they find themselves in,” Zuma said.

And as the Marikana Commission of Inquiry continues next week – on course to continue well into next year – it is a stark reminder of the challenges to equitable access to justice in South Africa. Experts blame the high level of poverty and associated marginalisation, particularly in the rural areas, lack of infrastructure and State capacity, the scarcity of legal skills in impoverished areas, illiteracy and ignorance of what the Bill of Rights and the Constitution entitles people to, for this imbalance in the access to justice in South Africa.

Farlam aptly reminded South Africans that the Marikana Commission sought ultimately to compel the State and its agencies to explain the intentions and motivations for their actions in Marikana publicly, fully and fairly, in the interests of a more just society.

“The Commission is an exercise in public accountability,” he said.

As an exercise in public accountability, however, its very process has proven how skewed access to justice really is in South Africa. DM

Read more:

- Marikana Commission: More questions than answers in Daily Maverick

Photo: Retired judge Ian Farlam speaks as the judicial commission of inquiry into the shootings at Lonmin’s Marikana mine gets underway in Rustenburg, October 1, 2012. (Reuters)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider