South Africa

Can we afford not to privately educate our children?

Last week the Centre for Development and Enterprise (CDE) published a report titled ‘Affordable Private Schools In South Africa’. This report is the third one produced by the CDE on private education choices for the poor and it examines the market dynamics of low-cost private education in much more detail. Whatever your feelings on state versus private education, it appears that the latter’s role in South Africa will become increasingly important. By PAUL BERKOWITZ.

It is generally accepted that the South African public education system suffers from many problems and deficiencies. Its harsher critics have described it as being in crisis. One of the unspoken assumptions that most of us make is that the poor face a Hobson’s choice when it comes to education: either they accept whatever the state dishes up or they go without any education at all.

A corollary of this assumption is that private education is the preserve of the rich and privileged. The popular image of a private school is of well-appointed grounds, a proud rugby or hockey legacy, and a musty pong of tradition.

Research by the CDE and others shows that this doesn’t have to be the case – poor households have a growing choice when it comes to education and the proliferation of private schools is in response to demand for poor- and middle-income families. In fact, the strong growth in low-cost private education is a global phenomenon, with over 50% of students from poorer areas in India, Pakistan, Ghana and Nigeria attending private schools.

The latest report released by the CDE is a logical progression from earlier research. In 2010 the centre surveyed six areas of the country with high levels of poverty and found that 30% of the schools in these areas were private. In the three years since then the centre’s investigation into low-cost private education has grown in tandem with the growth of the sector itself.

The exact number of independent (non-state) schools in South Africa is up for debate but some broad themes have emerged. Firstly the official statistics are a gross underestimate of the numbers: 4.3% of all schools are private according to the government, compared with the CDE’s estimate of 30% in poor areas. Secondly, there is a growth in school ‘chains’, where larger operators are opening a number of schools. These operators include Curro Holdings (listed on the JSE), Spark Schools, Nova Schools, and BASA.

Thirdly, these schools are cheap by South African standards but are expensive compared to low-cost schools in other developing countries. Very few of the large school chains charge below R10,000 for a year of schooling. This must be compared with R2,000 – R3,500 for schools in India and with fees as low as R360 per annum in Kenya.

Just like the public sector, the largest cost to private schools is overwhelmingly teachers’ salaries. These make up about 85% of all costs. The other large costs are related to physical premises (buying, renting and renovating buildings) and training materials.

The fact that South African public-sector teachers are among the highest-paid in the world (in terms of purchasing power parity) doesn’t make it any easier for the smaller private schools to attract and maintain talent. The problem is exacerbated by the bottom-heavy pay structure in the public sector; entry-level salaries are quite high but teachers with additional qualifications and skills don’t see commensurate salary increases. Smaller private schools live with the constant threat of having their teachers poached by the public sector, which can offer better salaries plus a host of benefits on top of this.

Some of the private school chains have managed to achieve economies of scale by, for example, centralising the management and administration of their different schools. There is huge pressure on private schools to achieve these economies of scale in order to remain financially viable. One option, as in India, is to increase the number of pupils per school, but this has a clearly negative effect on the quality of the education offered.

The private schools use what comparative advantages they have, which include a focus on the leadership of the schools. Emphasis is placed on finding and retaining the best principals and (increasingly) on training of teachers. The schools also focus on technological innovation and ‘blended learning’, which combines instruction from the teacher for the whole class and small group instruction with computer-based tools.

The costs of compliance, both in time and money, is also a barrier to entering the sector. It’s been claimed that independent schools face a higher regulatory burden than state schools do. The provincial education departments (PEDs) have also been cited as a source of frustration as they do not properly implement regulations.

PEDs have come under fire for their role in paying (or not paying) state subsidies to registered private schools. The payment of subsidies by the PEDs is governed by the National Norms and Standards School Funding (NNSSF) which the PEDs are increasingly ignoring.

Five provinces (KwaZulu-Natal, Limpopo, Mpumalanga, North-West, and Eastern Cape) have been accused of cutting subsidies to qualifying schools, not paying subsidies on time and failing to inform schools of the amounts due to them. In April 2013 the Constitutional Court ordered the KwaZulu-Natal PED to pay back some of the subsidy that it had withheld from schools. Similar judgments are expected to follow for the other PEDs.

There is good news. Commercial banks and development agencies are taking an increasing interest in the private education sector and are committing money to it. Some of the banks, and the DBSA, are tailoring their loan products for the needs of individual schools. In 2011 Old Mutual created a fund to finance infrastructure requirements for new and existing schools, for skills development, educational materials and services.

(In an interesting twist, the main contributor to the fund is the Government Employees Pension Fund, which could create a conflict of interest for SADTU members: do they try to shut down the competition or do they wish for their success and the growth of their pensions?)

What happens next to the sector, forced to run uphill on a clearly slanted playing field? The private sector and civil society are playing their part, in increasing numbers. Apart from the funds already committed by the banks there is the potential to channel more private-sector money into education, through corporate-social initiatives and the broad-based black economic empowerment framework.

Reforms to the education funding model would be welcome; any policy changes that lower the costs of regulatory compliance would make it easier too. These initiatives will not be supported from within the tripartite alliance, and SADTU will raise the volume if its members’ interests are threatened. Still, many across the public sector are recognising the important social role played by private education. Lobbying them may be easier than we think.

There is no turning back at this point, though. The sector has grown by almost 50% in the last few years without almost no support or awareness from the general public. There’s no denying the demand for a quality education, and the dedication of private-sector entrepreneurs who are not necessarily making a large profit (or any profit at all).

It’s time that the rest of us stopped lamenting the dysfunctions of public education and started considering the alternatives. The flow of money and other resources into private education will increase, but it doesn’t have to be in big, lumpy contributions from big institutions. It could be a small debit order from you or me. It could be a few hours of mentorship through organisations like this one.

Private education is filling the gaps that public institutions cannot: private-sector solutions are increasingly diverse, flexible and more relevant to the education needs of the future. Investing in private-sector education might be the best investment we make in future generations. DM

Read more:

- Report by the Centre for Development and Enterprise (CDE), ‘Affordable Private Schools In South Africa’

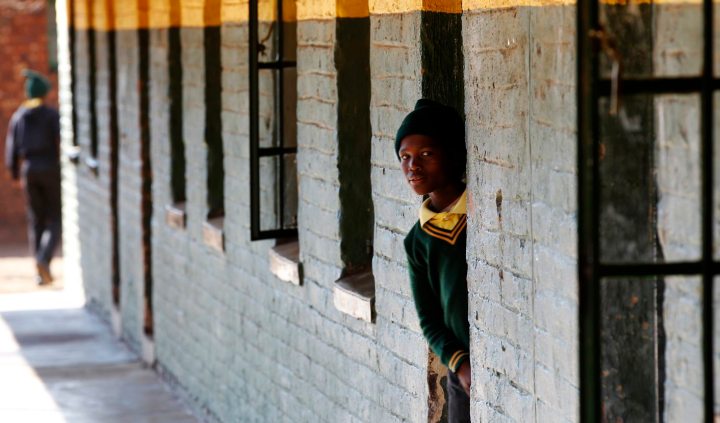

Photo: A student is pictured at a school in Khutsong Township, west of Johannesburg August 22, 2011. REUTERS/Siphiwe Sibeko

Become an Insider

Become an Insider