Business Maverick

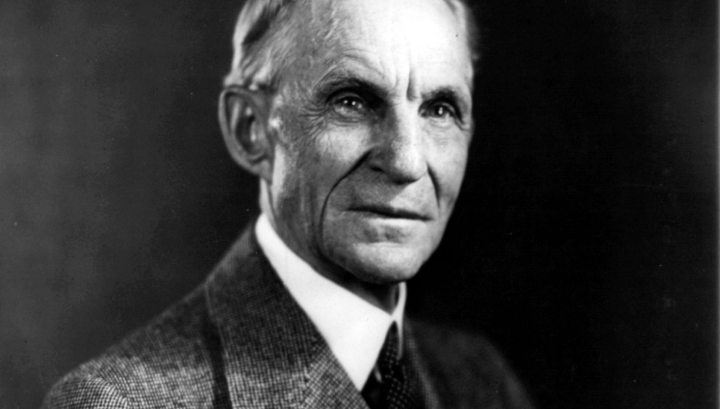

Henry Ford: The man who gave wheels to America

Henry Ford was born 150 years ago this week (30 July 1863). He didn’t invent the automobile; he didn’t invent mass production or the assembly line; but by harnessing these together he put country behind the steering wheel of an affordable motor vehicle that helped revolutionise society and manufacturing. Famous for saying the customer could have their Model T vehicle in any colour they wanted, just as long as it was black and his hopes for world peace through mass consumerism, he was nearly as infamous for his notorious anti-union strikebreaking at Ford assembly plants and his virulent anti-Semitism. J. BROOKS SPECTOR takes a look backward over Ford’s world.

This writer grew up in a working class suburb in New Jersey in a neighbourhood primarily populated by Jewish and Italian Americans. Many of these people were members of unions active in the factories nearby. While virtually every family was happily purchasing its family car and all the other consumer goods of the 1950s, very few if any of these people would have considered a Ford product as their automobile of choice – even if they admired the luxury of a Lincoln or the spaciousness and mechanical sophistication of a Ford or Mercury and flocked to see the ultra-sleek concept cars in the local Ford dealership down the street. Memories lingered a long time in this community over Henry Ford’s encouragement of physical violence in preventing unionisation in his factories – or his embrace of Nazi Germany and his affection for some pretty ugly, hardcore anti-Semitism.

Ford was in the second generation of manufacturing kings – following the success of the first round of industrial giants like John D Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, George Westinghouse, JP Morgan and others like them. He grew up on a farm in Michigan, but showed an early aptitude for tinkering – repeatedly disassembling and reassembling a gift watch – the hallmark of an inventor in waiting. After time at Westinghouse, he became an engineer with the Edison Illuminating Company. Working there gave Ford time and money for his personal experiments with petrol engines, leading to his 1896 Quadricycle, Ford’s first functional self-propelled vehicle.

That same year he finally met the renowned inventor and head of his company, Thomas Edison. Obviously impressed, Edison encouraged Ford in his experiments. Ford eventually left Edison’s company and became an independent designer and producer of his own early automobiles – although his initial models were less than successful mechanically and commercially. A series of additional ventures followed, including a promotional tour of his Model 999, driven by race driver Barney Oldfield, a tour that brought the Ford name to national attention.

Commercial lightning struck on 1 October 1908. On that day, the Ford Motor Company rolled out its first Model T automobile. Its steering wheel placed on the left side of the vehicle (consistent with the traffic patterns in America and an innovation that led every other manufacturer in the country to follow suit). But it also had a fully enclosed engine and transmission, the engine’s four cylinders were cast as a single block of metal, and it was equipped with a semi-elliptic spring suspension.

As a result, the car was both a revolutionary advance and a commercial bonanza – especially given its $825 price tag, and despite its severely limited colour range – black or black. As sales and production increased, the price kept falling so that by the middle 1920s, a majority of Americans had gotten their first taste of motoring behind the wheel of one of Ford’s Model T.

Besides revolutionising the design and manufacture of these thoroughly standardised vehicles, and introducing their production on a moving assembly line, beginning in 1913; Ford generated a major publicity effort and established a national network of Ford dealers. These locally owned, independent dealers worked together with a spreading movement of automobile clubs – thereby promoting the idea and joy of free, independent travel in one’s own car. Ford also reached out to the farm market, selling farmers on the idea a Model T could be a commercial vehicle for them as well as personal transportation.

Now Ford didn’t exactly invent the moving assembly line – thoroughly standardised manufacturing production was already the case beginning with early 19th-century innovations like Eli Whitney’s mass-produced military muskets and Joseph Marie Jacquard’s loom for mass-produced, complex-patterned textiles. But Ford took the ideas of several of his employees and refined them into the moving assembly line as the industrial standard of the age. In this way, workers maintained their workstation as the increasingly finished vehicles rolled passed them and they carried out their assigned part of the production process.

By 1914, sales of the Model T had reached a quarter of a million – and two years later, the price had dropped to just $360 as sales sailed upwards towards half a million units. And by 1918, half of all the automobiles in America were the Model T’s. Production of this basic version kept up at Ford’s factory until 1927. In total, production eventually clocked in at 15,007,034. By 1932, Ford’s company was building a third of the entire world’s automobiles.

In corporate terms, as the company continued to grow rapidly, Henry Ford and his son Edsel carried off a series of complex, sleight of hand manoeuvres to drive out all his other investors, thereby giving the family sole ownership of the entire company. However, by the mid-1920s, sales of the Model T were falling as they had to face increasingly strong competition from more modern designs being produced by competitor companies, and they were beginning to allow buyers to purchase the cars on credit payment plans. Eventually, Ford was forced to develop a new, more modern model, the Model A. The success of the Model A, with four million units sold through 1931, led the company to adopt the new idea of annual model changes, ie planned obsolescence, even if the basic machinery was largely the same. Ford also began to back the credit payment system for sales, establishing the company’s own credit arm for this purpose.

In social engineering terms, Ford was an early leader in what has been termed “welfare capitalism” – but he coupled this with an adamant opposition to any form of unionisation. His “welfare capitalism” was designed to increase the efficiencies in the hiring – and retention – of the best workers – by offering a paternalistic involvement in and the governance of employees’ personal lives. As part of this effort, Ford decided to offer a $5/day wage, effectively doubling the wage rate of most of his employees and establishing a shorter standard workweek.

Highly skilled mechanics soon were flocking to Ford’s Detroit factory, improving the company’s productivity and decreasing its training costs. This Ford initiative helped point the way forward towards the building of a working class that could afford a growing number of the products of mass produced consumer goods of the new modern age – including Ford’s automobiles. This new wage scale, or as Ford liked to call it, “profit sharing”, also came with corporate involvement in employees’ private lives, monitoring their behaviour to be on the lookout for gambling and drinking – although the tougher aspects of that approach were eventually toned down.

Perhaps trying to have it both ways, in his 1922 memoir, Ford had written, “paternalism has no place in industry. Welfare work that consists in prying into employees’ private concerns is out of date. Men need counsel and men need help – often special help; and all this ought to be rendered for decency’s sake. But the broad workable plan of investment and participation will do more to solidify industry and strengthen organisation than will any social work on the outside. Without changing the principle we have changed the method of payment.”

However, this paternalistic side of Ford’s approach came hand-in-hand with violent opposition to labour unions. Ford took the view unions were heavily influenced by leaders who would inevitably end up doing more harm than good for their members (and his workers). He argued that unions wanted to restrict productivity to spread available work around to benefit the maximum number of workers – but to the detriment of their employers’ interests. Ford’s view – a line of argument that continues to animate a debate about economic policy – was that while mechanisation would inevitably eliminate individual jobs, the overall impact would be to stimulate the economy as a whole, thereby leading to new jobs in other quarters. That meant union leaders had a perverse incentive to generate an ongoing workplace crisis so they could maintain their hold over union members. Conversely, good management had a larger social responsibility to do the right thing for their workers – not because of a love for their employees but because in the long run it would maximise their profits. Smart managers thus had an obligation to fend off the depredations of socialists and reactionaries to create his “Ford-ist” utopia.

To prevent the rise of the dreaded automobile workers’ union, Ford brought in goons to beat up union organisers. In one attack, one of the victims was Walter Reuther, an organiser who eventually went on to head the United Automobile Workers (UAW) union. In the most infamous incident in 1937, Ford’s security men bloodily assailed union organisers as local police stood by without intervening.

Watch: PBS Experience Henry Ford

Ultimately, it wasn’t until 1941, during a bitter sit-down strike organised by the UAW that shut down his giant River Rouge plant, that Ford agreed to come to terms with the UAW and allow the company to be unionised. But this only happened when Ford’s wife threatened to leave him if he continued to oppose unionisation, telling him that his stubbornness was about to wreck his own company.

Despite Henry Ford’s deep feelings about pacifism (or isolationism) during World War I and his support for a peace ship that sailed to Europe during the war to attempt to nurture negotiations between the warring alliances, his company eventually built engines for military aircraft. Post-war, his company began construction of the revolutionary Ford 4AT Tri-motor aircraft (sometimes thought to have been built on the lines of some purloined Fokker construction designs). The Tri-motor was often nicknamed the tin goose on account of its aluminium alloy outer skin.

As World War II approached in Europe, Henry Ford continued to believe “war was the product of greedy financiers who sought profit in human destruction” – going to the extremes of insisting the sinking of US merchant ships en-route to Britain by German submarines were the result of a secret conspiracy by financier war-makers, Ford’s not particularly subtle code for Jews. (Ford also felt President Franklin Roosevelt was surreptitiously driving the US into war on Britain’s side.) Ford had already been down that road, blaming Jews for stoking the outbreak of World War I.

As war broke out in Europe, while arguing his firm would do no business with belligerents, his company continued to do business (as did others like IBM) with Nazi Germany, even to the point of using French POWs as slave labourers. Nevertheless, when the US entered the war after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour, Ford’s company constructed a huge, entirely new assembly plant, Willow Run, expressly to build B-24 bombers. Ford ultimately produced half the nation’s wartime production of these planes – around 9,000 aircraft.

But by that period, age and illness had caught up with Henry Ford. After a series of strokes, the major decisions within the company increasingly fell into the hands of subordinates. Even after Ford returned to take control when his son, Edsel, died, it was a group of senior execs that ran the company. This group included Harry Bennett, Ford’s old security chief, the same man who had run a spying operation on employees and whose toughs had attacked union organisers.

With the company’s bankruptcy increasingly a real risk, Edsel’s widow then led a move to oust the company founder and put her son, Henry Ford II, in as president of a now-tottering company bleeding over a $130-million a month in current dollars. After having virtually created the modern industrial assembly process and helping to put the automobile right at the centre of American life, Henry Ford died on 7 April 1947.

Writing in Forbes magazine, Stephen Forbes wrote of Ford, “We’re all familiar with his name and company, but most of us don’t appreciate what an extremely important figure Henry Ford is historically. Plenty of people have founded giant, influential companies, but only a handful can match his impact. Ford did, indeed, invent the Modern Age. He was a mechanical genius, who realised early on that neither steam, which propelled the Industrial Revolution, nor electricity, which was gaining traction in both factories and homes, was the best means to fuel the automobile. It was the internal combustion engine, fuelled by gasoline.”

But Henry Ford’s life and work were also inextricably tied up with his deeply felt anti-Semitism. He sponsored the starkly anti-Semitic newspaper, The Dearborn Independent, that had published the virulent “Protocols of the Elders of Zion” (now known to have been fabricated by the Czarist secret police to help justify the pogroms), and Ford’s own volume, “The International Jew”, was an inspiration for Nazi Party leaders. Numerous articles written in Ford’s name for The Dearborn Independent were reissued in Nazi Germany in collected, bound sets, and Hitler had said of Henry Ford that he is, ”only a single great man, Ford, [who], to [the Jews’] fury, still maintains full independence… [from] the controlling masters of the producers in a nation of one hundred and twenty millions.” Hitler told a Detroit News reporter in 1931 that he regarded Ford as his inspiration, and that he kept a life-size portrait of the industrialist next to his desk. The Model T was apparently the original inspiration for Hitler’s vision of the people’s car, the Volkswagen.

Ford was clearly a bundle of some stark contradictions. While he strongly opposed unions, he pushed for an early kind of corporate socialism that increased wages and significantly improved working conditions. He preached pacifism and opposed war, but allowed the Nazis to embrace him.

Ford engineered an entire revolution with his products and their manufacture and pioneered the use of plastics and other synthetic materials; he built an extraordinary rubber estate in the Amazon River basin’s jungles, right from scratch, to feed his company’s need for rubber for tyres; but then he resisted modernising his Model T and Model A product lines, despite rising competition from other car manufacturers more willing to use new, improved designs for engines and other parts.

Ford had famously said, “History is bunk,” but then he spent millions of dollars on the Greenfield Village historical preservation park in Michigan (bringing together historic buildings like Thomas Edison’s famous laboratory) as well as Old Sturbridge Village, a reconstructed colonial town in Massachusetts.

Henry Ford’s footprint on the world has been such that the society described in Aldous Huxley’s dystopic novel, Brave New World, was created along “Ford-ist” lines – even the years in the book are referred to as AF (Anno Ford, in the year of our Ford) and “My Lord” became “My Ford”. Socialist campaigner Upton Sinclair turned Ford into a character in his novel The Flivver King, and Ford features as a character in EL Doctorow’s Ragtime as well. Even the central character in Harold Robbins’ novel, The Betsy (and the film it was made into), has clear and often uncomfortable echoes of Henry Ford. And, of course, Philip Roth made Henry Ford America’s secretary of the interior under a President Charles Lindbergh, in his dark, brooding alternative history treatment of World War II America, The Plot Against America.

This hugely contradictory figure accepted Nazi Germany’s Grand Cross of the German Eagle decoration, even as he features on an American postage stamp, part of a series that extolled American ingenuity. And, of course, his name still appears on countless millions and millions of automobile nameplates all around the world. DM

Read more:

- Henry Ford May Have Been Bigger Than Gates, Jobs, Brin and Page at Forbes;

- Inside the decaying ruins of Henry Ford’s failed rainforest city ‘Fordlandia’ based on suburban Michigan at the Daily Mail;

- The Life of Henry Ford at the website of the Henry Ford Museum;

- Henry Ford at Biography.com.

Photo: Henry Ford.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider