Maverick Life

‘Of Good Report’, Sugar Daddies and Vavi

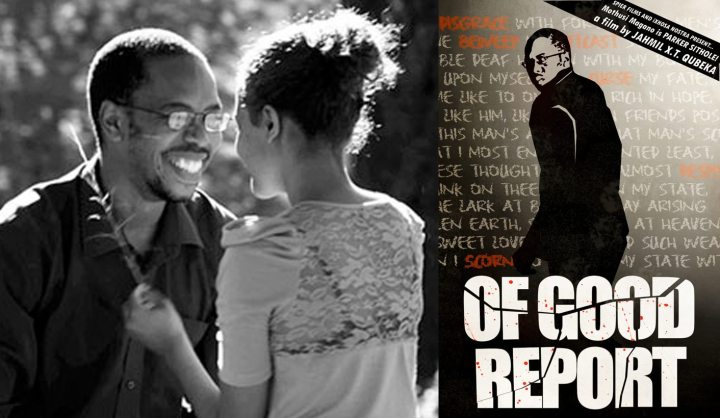

Now that you can finally watch the most talked-about film in South Africa without breaking the law, the previously-banned ‘Of Good Report’ was screened to media in Johannesburg and Cape Town on Tuesday. The film is quite clearly no reasonable person’s idea of child pornography, as the Film & Publications Board claimed. But it also raises questions about “consent” in a sexual context, which has troubling relevance to the Vavi context. By REBECCA DAVIS.

Let’s cut to the chase: Of Good Report is not remotely pornographic. Indeed, those of a prurient mindset, who the FPB’s ruling will probably send flocking to the film in the hope of being treated to lashings of explicit sex, will likely leave the cinema deflated. The sex scenes are short, tame (one features both parties fully dressed) and by no reasonable person’s stretch of the imagination could they be considered gratuitous. Indeed, if you are of a delicate disposition, you are likely to be more offended by the violence in the film than the sex. There is a scene where a woman’s corpse is strung up by its feet, close to the end of the film, which is quite jolting.

But we know for a fact that that scene wasn’t viewed by the FPB, because they only made it through the first 28 minutes. Perhaps the most disappointing aspect of the FPB’s approach throughout this farce has been their utterly unrepentant attitude. Since the unbanning of the film, the body has said that they remain “disappointed and saddened” about losing the classification war, and that if they had their way the film would still be classified as pornography.

This is sticking to your guns in a way that verges on delusional. In the appeal hearing, lawyer Steven Budlender, appearing for the film’s director (Jahmil Qubeka) and Spier Films, argued that the film was “self-evidently a serious work of substantial dramatic merit”. This is absolutely right; it’s one of the better South African films in recent years, in fact, and the real sadness of the FPB’s nonsense is that the film’s intrinsic merits may be drowned by all this confected controversy.

Budlender drew heavily in his argument on a previous ruling by then Deputy Chief Justice Pius Langa, who wrote: “Some forms of pornography may contain an aesthetic element. Where, however, the aesthetic element is predominant, the image will not constitute pornography”. The definition of pornography, Langa wrote, also required that the image should have “as its predominant purpose the stimulation of erotic feelings”, rather than any aesthetic feelings. Langa also noted that determining whether images constituted child pornography could not be determined without reference to the context – something the FPB evidently failed to do when they didn’t even watch the whole movie.

Budlender also argued that if the current FPB were to apply its eye to past films, among others to be classed as child pornography would be The Reader, 2008’s Best Picture Oscar nomination, which showed a 15-year-old boy having sex with an adult woman; and Risky Business, the 1983 film which shows a teenage Tom Cruise having sex with a prostitute. Books containing scenes of child rape – like Alice Walker’s celebrated novel The Colour Purple – would suffer a similar fate.

You don’t have to be a film archivist to quickly think of other films which the FPB should have banned, working off their current arguments, but inexplicably didn’t. The year 2006’s award-winning Notes on a Scandal, in which Cate Blanchett’s high-school teacher character is shown having sex with a 15-year-old male student. The year 2009’s lauded An Education, which shows Carey Mulligan’s 16-year-old schoolgirl being seduced by an older businessman.

It will also be interesting to see how the FPB will handle a number of films which should be due on our shores soon. Blue Is the Warmest Colour, the French film which took top honours at Cannes this year, features an affair between a 15-year-old girl and her older female teacher, including one sex scene which apparently lasts 12 minutes. That, surely, doesn’t stand a chance.

No, Of Good Report is not pornography. It is a fine, serious, ambitious, beautifully-shot and well-acted piece of art. Its black-and-white styling borrows self-consciously from film noir, with touches of intentional absurdity. Qubeka succeeds in creating an atmosphere of genuine creepy tension, and is ably aided in this by a remarkable musical score from Philip Miller, deserving of individual plaudits. The film’s main character – teacher Parker Sithole – is played entirely silently by Mothusi Magano, who uses only his face and posture to give a convincing account of a man struggling with his desires.

Overseas audiences may see Africa as never before, because Qubeka’s monochromatic lens eschews any scenic delights. Interiors are alternately claustrophobic and isolating, echoing Sithole’s interior world. The landscape is harsh and uninviting. A number of climactic scenes are shot in the rain. But this is recognisably South Africa, a place where teachers are not the only fallen idols. A Zuma election poster hangs sideways forlornly from a post; the camera swings from registering a heinous act being committed to the tattered poster of Hansie Cronje that overlooks the scene.

The schoolgirl for whom teacher Parker Sithole falls is called Nolitha, an obvious Nabokov allusion, and at the end of the film the reference is made perhaps unnecessarily clear by means of a shot of Lolita on a school desk. Actress Petronella Tshuma is 23 but makes a plausible 16 – perhaps one factor that threw the FPB into disarray. The character is consciously grasping towards adulthood: at one stage she pulls cigarettes out of an achingly juvenile schoolbag (with mandatory tippexed name of owner) and lights up, post-coitally.

Of Good Report is now being framed very much as having been intended to prompt a conversation about so-called “sugar daddies” and inappropriate student-teacher relationships. But speaking to journalists after Tuesday’s screening, director Qubeka seemed to admit that his real intentions were different. “I suppose it’s a bit shallow, but I set out to make a serial killer origins story,” he said. That the film is now being presented as a sugar-daddy talking point may owe something to the need to underline its importance for the benefit of the FPB; and something to the idea that “important” art, particularly in South Africa, has to be issues-based.

But by definition, the film does lead one to think about student-teacher relationships. Of Good Report’s media release describes it as “Little Red Riding Hood, told from the wolf’s perspective”, but in fact this does the film too little credit. Where it succeeds, indeed, is conveying something of the complexity of this kind of relationship. It is Nolitha who approaches Sithole in a tavern, not the other way round; when he first beds her, he has no idea that she will be his pupil. As the relationship unfolds, it is depicted as not just consensual but mutually-rewarding. Both look happy.

This is, of course, a controversial idea, and the film ends up charting a very safe moral course: in this respect, it loses much of the ethical complexity of Nabokov’s novel. The accepted response to student-teacher relationships is to deplore and condemn them, on the entirely valid basis of the vast power discrepancy that underlies such a relationship. There are practical as well as moral reasons for disapproving of such relationships: research has shown, for instance, that intergenerational sexual relationships have fuelled the HIV epidemic within sub-Saharan Africa. One study found that for every year’s increase in the age difference between partners, there was a 28% increase in the odds of having unprotected sex.

Cosatu General Secretary Zwelinzima Vavi, as is now widely known, had unprotected sex with his subordinate, a woman of 26: 24 years his junior. Vavi was not her teacher, and women of 26 may be taken in most instances as being vastly different in maturity and experience from a teenager of 16. But the unequal power relations in this situation are nonetheless troubling, and have been avoided by many commentators who choose to focus instead on Vavi’s “poor judgement”.

True, Eusebius McKaiser cautioned against the assumption that the junior partner must inevitably be the victim in this situation: a valid, and valuable point. “Sometimes older men and women, seemingly powerful, can be the pathetic disempowered partner in an affair,” McKaiser wrote. But the fact remains that it was Vavi who hired the woman, seemingly with disregard for protocol, and it surely must not have escaped her mind that one who hires so whimsically may also fire in the same manner. In the transcript of messages between Vavi and the woman, released by Vavi himself, it is notable that she refers to him as ‘GS’ (General Secretary). That does not suggest a relationship of equals.

What does ‘consent’ mean in a situation where one’s livelihood depends on the person asking, or not asking? Many women and many men will know how difficult it is to say ‘no’ to a boss in many other benign contexts. How come sex – with all its additional social baggage – is considered so easy to refuse from the person who signs off your pay cheques? Is this really ‘consent’?

These are complicated questions, and in the case of Vavi and his employee, there appears to be little evidence for outsiders to judge on. But a country that recognises that even consensual teacher-child relationships are deeply problematic should consider applying that same awareness of power dynamics to a boss-employee affair. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider