South Africa

The truth, endangered: Miners’ representatives withdraw from Farlam Commission

The Legal Resources Centre (LRC) has provisionally withdrawn from the Marikana Commission, joining the other two parties representing the injured and accused miners as well as the families of the 34 miners who were killed last year in the Marikana Massacre. The LRC represents the Benchmarks Foundation and the Ledingwane family, who asked the LRC to not continue with the Commission at present. In light of this, what chance of the Farlam Commission finding a truth about the massacre? By GREG MARINOVICH.

The first party to withdraw was that of advocate Dali Mpofu and his team representing the 276 miners who were arrested in the aftermath of the massacre, as well as those injured by police fire on 16 August 2012. They were then joined by Socio-Economic Rights Institute of South Africa (SERI – who briefed advocate Dumisa Ntsebeza and his team) who represent the families of the deceased as well as AMCU.

Mpofu last week brought an urgent application before the High Court to try to force the state to extend Legal Aid South Africa funding to his clients. Legal Aid had already made a decision to fund SERI at the Commission, so this does not seem too far a stretch, yet the state and the presidency have vigorously opposed it.

So all of the teams representing the striking miners have withdrawn – at least until the North Gauteng High Court hands down its decision tomorrow or Friday.

It is an awkward situation – it is clearly undesirable not to have these vital participants there. It certainly appears unjust for the state to refuse to fund the victims and survivors at subsidised legal aid rates while it continues to fund the SAPS legal team as well the department of mines team on full commercial rates of between R38,000 and R45,000 a day for each senior advocate.

The Commission will sit again Thursday with only the police, the NUM and Lonmin as affected parties represented. Other civic organisations will still be represented – those who do not represent the families or the miners. Should the judge rule in favour of the state paying legal aid fees, then everyone will return and the Commission will continue with full participation.

Yet this diversion has shone a light on the pace, as well as the nature of the Commission. The Commission is due to wrap up in October. At the current rate, this means that only three more witnesses will appear to give evidence.

The Commissions’ own evidence leaders have a list of between 33 and 35 more witnesses they wish to appear. The sums do not add up. Even at a cracking pace, which has not been seen until now, the Commission would not get through those dozens of witnesses.

Of course, the other parties have their own witnesses they would like to see giving evidence.

It would seem that the president would have to extend the Commission’s lifespan if it were to get through even the first phase of the inquiry with any decency. But even an extension to December seems too optimistic a cut-off time. In submissions to the High Court, the Presidency and the Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development are adamant they will not extend it.

Despite it being too short to allow everyone their voice, the longevity of the Commission is creating other issues. There are consequences to the slowness of its work. Any criminal or civil action against the police or others is weakened by delays – some witnesses have already met sorry ends (murdered or have committed suicide), others get ill, memory fades. Public interest naturally starts to wane, and fickle societal attention moves onto other subjects.

There is also the technical point that when suing the police, one has to lodge notice within six months that you intend to sue and then you have to launch summons in a reasonable time. One hopes all this has indeed happened.

Politically, it is very convenient for a supposed progressive government led by a former liberation party with impeccable credentials to want to minimise the dirt that will inevitably rub off on it once the full facts around Marikana are known. Some observers are convinced that Marikana was the result of the confluence of politics, business and unions colluding against the interests of an impoverished labour force.

The desire to obfuscate this is especially strong as the African National Congress gears up for what will be its toughest electoral battle ever, where it will face spirited competition from established parties and its own breakaway Economic Freedom Fighters, led by its prodigal son, Julius Malema.

There are also persistent rumours that the presidency has been in talks to persuade retired judge Ian Farlam to delay any report on the Marikana massacre until after the April 2014 ballot. One assumes he will not be swayed by this, but it matters not, as this inquiry is at the President’s pleasure, and he has no legal obligation to reveal any of the findings or recommendations.

While the Commission plays a vital role in helping the nation understand what happened and for which reason, it is clear that like many Commissions of Inquiry before it, it could well be used to divert and delay justice.

Civil society is being bled dry by the costs of this lengthy process. There is a limit to how much funding the various law-based human rights watchdogs can muster for this battle. And who then will fund the criminal and legal cases that are set to follow?

Perhaps this principled, or avaricious, move by the miners’ legal counsel, and its concomitant support, has helped to clarify the main issue: the Commission is not about delivering justice itself, and it has no power to prosecute anyone.

Is it not time that bodies like IPID, which has refrained from charging the policemen who fired their weapons at Marikana until after the Commission has made findings, and the families of the deceased to lay civil and criminal charges against the Minister of Police, the Police Commissioner as well as the individual cops on the ground that day?

Marikana is a word that is now seen to describe the struggle an underclass – of the working poor who feel under-represented by our democracy and oppressed the state and its organs. The Commission has the opportunity to be the voice of justice for this underclass. South Africa, let it not fail. DM

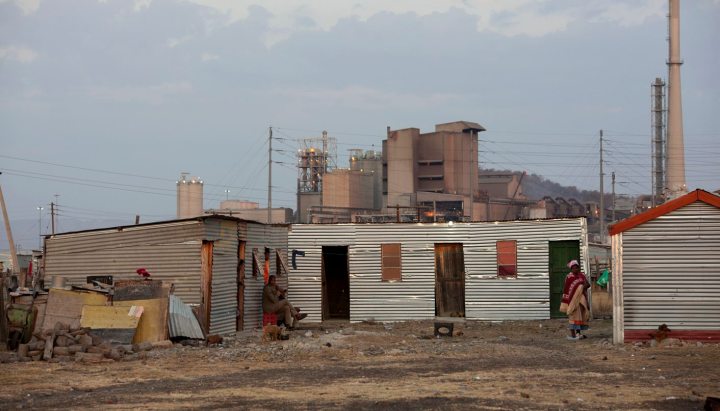

Photo: Marikana, 9 July 2013 (Greg Marinovich)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider