Maverick Life

Mountains, Memory and Memorials

Four years ago, the play, “The Mountaintop”, by the young, virtually unknown playwright, Katori Hall, appeared on stages in both London and New York. It had won a Lawrence Olivier Award for best new play, been given rapturous accolades in its two London productions, been performed in New York City with A-list stars Samuel L Jackson and Angela Bassett cast in the play’s two roles – and triggered a vigorous debate about the way the arts should treat a national icon. And all this before the playwright was 30 years old. Now this play is being performed in Johannesburg’s Market Theatre, even as South Africa is increasingly engaged in its own discussion about how to treat its own preeminent national icon. J. BROOKS SPECTOR takes a look.

Katori Hall’s play is a “what if” fable. What might it have been like if Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., weary from his meetings with the Memphis rubbish collectors, returns to his down-at-the-heels room in the Lorraine Motel the night before his death, had encountered a motel housekeeper with a difference. When King tries to get some coffee through room service to give him the strength to tackle his next speech, Camae comes into his room with the room service tray and the two characters banter, trade insults, engage in a little philosophical foreplay – as it becomes increasingly obvious she is rather more than your usual garden-variety motel employee. This Market Theatre production stars veteran film/television and stage actor Sello Sebotsane as Martin Luther King and Mwenya Kabwe as Camae, the housekeeper. The production is directed by Warona Seane, with lighting, set and costume design by Wilhelm Disbergen.

When Hall’s play was first staged in 2009, The Independent (UK) said of her work, “Pastor King is finding his own job a bit trying. He’s just come back from delivering a speech on the plight of sanitation workers at the Mason Temple in Memphis; it’s pouring down with rain and he’s stuck in a damp motel room. He’s also been hounded by assassination threats. It is a relationship that is breath taking, hilarious and heart stopping in its exchanges and in its speedy ability to reveal character and pull the audience into the ring…. We discover, too, that King has stinky feet, wonders whether his moustache looks good on him or not and has an eye for the ladies. We also learn that he is terrified. Terrified that he is about to die, that the attempts on his life will finally get him. Terrified that he hasn’t had the chance to fix the world and that he hasn’t said goodbye to his wife and children.” In this premiere, David Harewood, an actor who coincidentally had also taken on the role of Nelson Mandela in a BBC TV biopic, was Martin Luther King.

The Guardian also rhapsodised about the work, saying, “The black American playwright Katori Hall grew up in Memphis, close to where King was shot. Her playful two-hander, set in a room in the Lorraine Hotel on the night before King’s death, asks whether, in the years between the assassination of King and the election of Barack Obama, black Americans really have reached the mountaintop, or merely got stuck halfway up.… [Is] Camae [the hotel employee], who has her own Black Panther-style rhetoric and insists God is a black woman, quite what she seems? As initial flirtation turns to serious talk, it becomes apparent that Camae brings far more than just coffee, including the opportunity for King to have a one-to-one chat with God, who has just popped out of heaven to sort out a forest fire.”

By the time Hall’s play won its Olivier Award, the expectations bar had been set pretty high for its New York City production the following season. That NYC production brought together Samuel L Jackson and Angela Bassett for very rare, live stage appearances. The New York Times drama critic Ben Brantley wrote, “Even before the first flash of lightning – and there will be plenty of that before evening’s end – an ominous electricity crackles through the opening moments of ‘The Mountaintop’….” But despite praise for the actors’ performances, some US critics like Brantley felt the play was ultimately a kind of comfort play, a “fable for grown-ups that seeks to reconcile us with a tragedy that tore the fabric of a nation”.

Perhaps the difference was in the way British audiences see America, versus the way Americans see themselves, their homegrown heroes and their racial conflicts. Brantley commented, for example, “A sleeper hit in London, where it won the 2010 Olivier Award for best new play, ‘The Mountaintop’ arrives on Broadway attended by great expectations and the scepticism that some New York theatre-goers may feel about British-endorsed, American-themed productions.”

Many Americans go into a kind of gushing rapture for a British period production like “Downton Abbey”, while the British seem positively enamoured with productions that point at some hidden, deep flaw in the American national character. As Anita Gates, reviewing yet another production of “The Mountaintop” noted, “Maybe this is not a work of staggering genius and sociological insight. Maybe it just made the British, who saw it first, feel good about what violent, ignorant bigots Americans must be, killing the 20th-century civil rights leader who seemed to stand most clearly for nonviolence and God’s love.”

But perhaps, too, a key part of the problem lies in plucking real historical figures from life and inserting them in a drama for the stage. (Film and television both seem to be a different thing. People love those biopics that depict a stalwart, heroic, historic figure’s failures, flaws, struggles and eventual triumphs. No one wants to watch a loser, after all. Churchill is a better subject than Chamberlain, right?) And Shakespeare, of course, had famously imbued the Tudor dynasty – and, by association, his sovereign, Elizabeth I – with a sense of inevitability and fitness for the throne via his portrayals of Elizabeth’s near predecessors.

But in dealing with more recent circumstances, playwrights face a dilemma when they create dramas about or of history. Part of the problem is that if audience members have followed the news or read some history, they already know the best parts, the best lines, and the conclusion.

There are, of course, those popular one-person shows that are like a pleasurable after-dinner conversation with a famous figure like Mark Twain, Charles Dickens or Harry Truman, engaged in a ramble through a scrapbook of life’s great events and their famous sayings or writings. The story line here is less history and much more a vivid personal profile.

But watching a play like, say Jerome Lawrence and Robert E Lee’s “Inherit the Wind”, instantly recalls a certain Tennessee science teacher who went on trial in 1925 for teaching evolution; that he was defended by crusading lawyer Clarence Darrow and prosecuted by Bible belt politician William Jennings Bryan – and that the trial had been famously reported by HL Menken. And to see Saul Levitt’s “The Andersonville Trial” usually means coming into the theatre already knowing the North won the American Civil War but that its prisoners of war held in the South had been abysmally treated. To watch Brecht’s “Galileo” simply requires only a tincture of knowledge about the battle between religion and science at the beginning of the modern era.

As a result, in tackling actual history, the playwright’s choice is either to create a play that is effectively a chronological but tightly written recapitulation of what is already in the history books – or somehow find a masked personal dimension to the story, uncover a bit of hidden history, offer a tantalising “what if” version of things – or provide a translation of the actual into the realm of psychological fantasy. For example, in “The Meeting”, another earlier, still-popular play about Martin Luther King, the playwright’s hook is to draw on the historical fact both Malcolm X and King had been in New York City on the same night, just before the date Malcolm X was assassinated and posit a “what if” drama: What if the two men had secretly met that night in King’s hotel room and debated the nature of social change, the future of America’s race relations, the plausibility of integration in contrast to black separatism or black nationalism, and the virtues of violence versus nonviolence as the right tool for progress. Playwright Jeff Stetson draws on both men’s actual recorded words and builds a text that is a staple of black repertory theatre companies and university theatre programs in America (and was also done at the Market Theatre in 1992) – in part because the arguments given to the two men are still potent for many.

Katori Hall, of course, chooses a very different tack (spoiler alert here). She creates a universe where the bone weary Martin Luther King, increasingly disillusioned at the hills he still has to climb to achieve “the promised land”, is fearful of death and in a struggle with his inner demons as well as the text of a speech that will not come to his pen. On the eve of his assassination, he has met his personal angel of death – in the persona of a motel housekeeper who greedily smokes Pall Mall cigarettes, swears like a drunken sailor and makes a telephone call to God to let King plead his case for just a bit more time.

In this Market Theatre production, Sebotsane plays King more like a tired Willy Loman than conflicted Baptist preacher, while Kabwe finds the quicksilver changes needed for the role of Camae the housekeeper/angel of death. Kabwe has a way with one of the most difficult of things for a South African actor – those rolling cadences of the convincing Deep South, black American accent.

But despite the fantastic story elements, the play’s strength must derive from the believability of this fantasy – we know, after all, that James Earl Ray’s rifle shot will snuff out King’s life the next day, that a wave of urban riots will consume cities across the US in the following days – but that ultimately, too, that nation will embrace a black man as its president in the beginning of the 21st century. If there is a difficulty to the structure of this play it may be that it is challenging to decide just where it should come to an end – should it be at the sound of a clap of thunder, at a rifle shot, or perhaps with King as a Christ-like figure, suffused in a light from above?

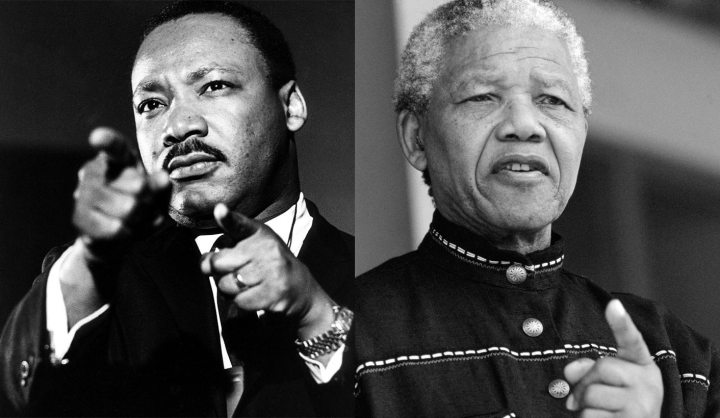

Of course, too, one difficulty playwright Katori Hall tackled in her work is also one of the challenges that South Africans will eventually face as they address how to situate their preeminent national hero in literature, art and drama. Numerous dramatic and documentary films and TV biopics have already depicted a Mandela for both current and future generations, and he has already even been portrayed in two operas. But there will be many more works to come. For both King and Mandela, the creators of monuments have been busy – statues of Mandela already are in place on prominent hillside overlooks and even at the entrance to one of the country’s best-known shopping malls. And his face is now on all of the country’s paper currency as well as numerous street signs. And, in advance of the inevitable, sharp merchandisers are already flogging the sale of Mandela gold plated, memorabilia medals via the Internet. In America, meanwhile, Martin Luther King’s visage is on the newest monument on the downtown Mall – the so-called nation’s front yard – in Washington, DC as well as a national holiday in the calendar. (Interestingly, were King still alive today, he would be a decade younger than Madiba is now. Now there is the kernel of an idea for a play, yes?)

But the challenge of figuring out how to recognise, memorialise, monumentalise national figures continues. Most recently, following the reopening of the renovated Nelson Mandela Centre for Memory, the institution announced plans to intensify the celebration of Nelson Mandela International Day, this time marking Madiba’s 95th birthday on 18 July – and broadening the forms of participation that come from giving back to the community via individual commitments of 67 minutes per person, rather than just the building of yet another monument. Of course the film version of “Long Walk to Freedom” will be coming to cinemas by the end of this year – although we may yet be spared the horror of tie-in sales of Madiba action figures and beach towels.

Further ahead, it will be fascinating, two or three decades from now, to see just how South Africans choose to memorialise – and interpret – the legacy of the nation’s first black president. Will there be a new Mount Nelson Mandela Hotel in downtown Cape Town, or a slew of brilliant new plays and films focusing on the torments and temptations of Nelson Mandela while he was in his cell on Robben Island – or will the country’s most popular 3D computer game be one pitting the holographic image of Madiba against that of De Klerk? DM

The Mountaintop is now on at the Market Theatre until 21 July 2013

For more, read:

- Theater Review | ‘The Mountaintop’ at the New York Times;

- Was Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. An Ordinary Guy? At the NPR;

- Tell It on the Mountain at New York Magazine;

- The Mountaintop – review at the Guardian;

- Nelson Mandela International Day at the Nelson Mandela Centre for Memory;

- The Mountaintop is surprise winner at Olivier awards at the Guardian;

- The Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial at the Washington Post;

- In Room 306 of the Lorraine Motel, the Last Night it the New York Times;

- Playwright Katori Hall: Young, gifted and fearlessly redefining theater at the Washington Post;

- Twitter, Eggs and ‘Mob Wives’ at the New York Times;

- Theater Review (Washington, DC): The Mountaintop by Katori Hall at Arena Stage at Blogcritics.org

Photo: Martin Luther King Jnr, Nelson Mandela (Greg Marinovich)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider