Maverick Life

Remembering Aziz Hassim, a son of Durban’s Casbah

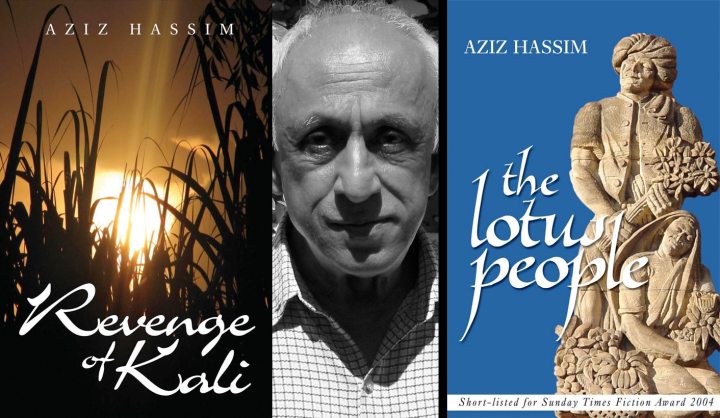

Last Friday, a giant of South African literature, Aziz Hassim, passed on. He leaves behind a legacy of literature and activism that celebrates Durban’s Casbah. By KHADIJA PATEL.

The Grey Street Literary Trail has lost another of its great writers. Aziz Hassim passed away on Friday 14 June 2013 after battling pneumonia in hospital for ten days.

“Writing is my own personal [Truth and Reconciliation Commission],” he had earlier said. “It’s the only way that I can record the untold history of the Casbah.”

Born and raised in Durban’s Casbah, Hassim believed where he lived and the people he grew up with had a profound impact on how he viewed the world. Although he began writing late in his life, he became one of the most important voices to emerge from South Africa in the last 20 years.

In his debut novel, The Lotus People, readers are transported to the world of Durban’s Casbah, which some academics believe is just as important in the literary-political imagination of South Africa as Soweto, District Six or Hillbrow. What emerges through the novel is a sense of the Casbah as more than just a physical space. The Casbah was also a particular time in history, coloured by circumstance and forsaken by history.

Hassim’s son, Anice, says: “He loved Durban. He was a well-travelled man but he never lost sight of where he came from. And he always believed that where you came from was most important – it was the community that made you.”

He says his father embodied the spirit of the Casbah.

“You really understood that it didn’t matter if you were coloured or black or Hindu or Muslim or Christian, you supported each other and you looked after each other because your common cause was poverty, your common cause was a lack of education, your common cause was the potential of a failure of hope in the community. And he just lived that.

“For a man of his generation – he was born in 1935 – to battle against economic hardship as well as Apartheid, he only got a Standard eight education and he left school to support his family, but he was a rare thinker,” Anice says.

But there were extensive periods of trouble. “There were times when he couldn’t do anything except work and put food on the table,” Anice adds.

It was at the ripe old age of 68 that Hassim began a new life as a writer.

“The one thing he’s teaching us is to look beyond our fences, beyond our fences of race and class and history and realise, ‘We’re in this together,’” Anice says of his father’s writings.

The Lotus People, which was not yet in the public sphere at the time, won the 2001 Sanlam Literary Award for an unpublished novel. At the time poet and author Stephen Gray said of the novel, “It is one of those one-off, unpredictable things … an absolute masterwork that has never seen the light of day.”

The Casbah, or Durban’s Grey Street complex – also known as as Coolie Town – is centred on what is now Dr. Yusuf Dadoo Street. It is seen as Durban’s equivalent of Sophiatown or District Six, and was a predominantly Indian area that was destroyed by the Group Areas Act.

Hassim often said he grew up “in the mean streets”. Beyond the sense of community and multiracialism, life in the Casbah was also coloured by gangsterism, gambling, business and, of course, politics. Hassim wrote:

“Life in the Casbah was about politics too. Children were weaned on it, as children elsewhere were weaned on mother’s milk. It was the logical outcome of the policies of repression, the common denominator around which their lives revolved. Spectators watched sport and simultaneously talked politics, diners enjoyed their meals and discussed the latest developments, young couples impressed each other with their awareness and the depth of their knowledge, and street sweepers picked up pamphlets and debated the merits of protest as a force for peaceful change. There was no other area of under one square mile that could equal it for the intensity of its emotions and its pursuit of justice.”

Omar Badsha, photographer, activist and the founder of South African History Online, also hails from the Casbah. He believes nostalgia for the Casbah has emerged in recent years – a nostalgia he sees Hassim as integral to curating.

“There is an incredible nostalgia about that period, whether it’s the Grey Street area or Sophiatown or District Six. I think most people from that generation and their children are now trying to reconstruct that era,” Badsha says.

Badsha also credits this reconstruction to memory and loss.

“You had the Group Areas imposed on the country and that devastated and uprooted the community. The fact that 80% of the people of Durban were moved – whether they were African or Indian or Coloured – black people were moved from where they were living for over 100 years,” he says.

Anice tells of his father: “In the last 10 or 15 years he really tried to find a way to cut through all of the issues and show people a sense of Durban that they could rally around.

“He fought so hard to protect that Casbah, the memory of it.”

Beyond the idealisation that comes with nostalgia, Anice says there was a real sense of community in the Casbah. “Look, here are people who lived together not necessarily in a sense of ‘Kumbaya and we shall overcome’, but there was a kindred harmony of community and togetherness, and it didn’t come from a sense that you were a fellow Hindu, or a fellow Christian, or a fellow Indian, or a fellow Hindu, it came because you lived in that area. You depended on each other for survival, for succour, for support – people living in peace and alignment, a bit romantically, perhaps, but that was a dream.”

In July 2009, Hassim launched his second novel, Revenge of Kali, which takes place in Durban’s Warwick Triangle in the 1960’s and 70’s. That novel tells the tale of indentured Indian South Africans and the infamous “Grey Street System.”

Hassim said, “While The Lotus People is a novel about what the Apartheid regime did to the Indian community, Revenge of Kali is about what the Indians did to themselves.”

The book was criticised by some as a subliminal attack on the Hindu religion. “I don’t know what the fuss was about. Yes, Kali is a Hindu god, but I do not speak badly about the Hindu community in my book,” Hassim said in response to the criticism. “I write what I know and what I see.”

Hassim never shied away from criticising the South African Indian community, however.

“I’m worried about the lack of tolerance within the Indian community and South Africa as a whole,” Hassim told MindMapSA. “If a person of your own colour bumps you, you apologise, but if someone else bumps you, people start fighting.”

Anice believes his father has a universal relevance, despite initially appealing to a niche audience. “People think he’s only of interest to Indians because he’s an Indian author, and the reality is that so many people in Durban and in South Africa, in general, discover his books and his writing and are delighted and are transported to a completely different world,” he says.

Anice says Hassim’s family – he, his mother and three sisters – have been bowled over by the sheer outpouring of grief from the people Hassim knew.

“He leaves an inspiring legacy of affecting lives in what we’re discovering as quiet and modest ways; individually but collectively they were transforming to a community,” Anice says.

“He was not a public person, but he was involved at the cutting thrust of some of the most important debates and speeches.”

Anice believes his father’s death will be a sizable loss to his community, and that he provided inspiration to many living similar lives. “He was a true son of Durban,” he says. “There are probably a million Aziz Hassims across South Africa right now who are living a quiet life of dignity and struggle.” DM

Read more:

- Memory, Literary Tourism And Aziz Hassim’s The Lotus People on KZN Literary Tourism

- Conversations with Aziz in MindMapSA

Photo of Aziz Hassim by Niallmcnulty

Become an Insider

Become an Insider