Africa

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam: Egypt and Sudan move from denial to acceptance

When it’s completed in 2017, the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam will be one of Africa’s flagship infrastructure projects with the potential to kick-start both power and agriculture development in Ethiopia. But downstream countries are worried that putting a massive dam on the Nile will affect their own precious water supply. Don’t worry, says SIMON ALLISON – managed properly, there’s plenty of water to go round.

As natural resources go, water is a strange one. It falls from the sky and evaporates back up there. It flows into countries and back out again, through seas and across continents. It’s difficult for anyone to own water in any significant quantity.

All that governments can do, really, is to try and control it – to regulate where exactly it flows and how much of it flows at once. When countries talk about securing their water supply, this is what they’re trying to do – it’s not necessarily about stockpiling billion and billions of litres.

Controlling the water supply is what, for example, the Lesotho Highlands Water Project is all about for South Africa. The water that falls into Lesotho and then flows down its mountains does not belong to Lesotho. Left to its own devices, the water will flow into South Africa anyway, mostly through Aliwal North in the Eastern Cape. So South Africa is not paying Lesotho for the water itself, but for the privilege of diverting it in a direction that is useful for us (into Gauteng) and building dams to keep it flowing at a pace that we can dictate. It’s a win-win situation: we get the water where we need it, when we need it; and Lesotho gets a whole lot of cash (Lesotho being too small to possibly use all its water supply).

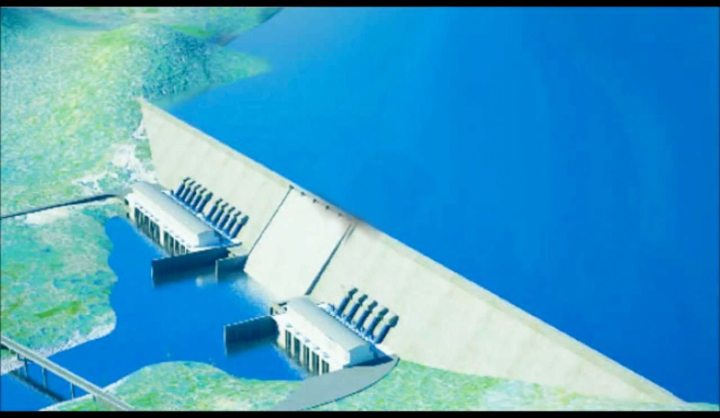

Things are a little more contentious at the other end of the continent. Earlier this week, in the Ethiopian region of Benishangul-Gumuz, engineers broke ground on a project that will divert the course of the Nile by about 550m. This is just a temporary diversion, but one that will allow other engineers to start work on a much bigger project: a huge dam, twice the size of Singapore, which will generate around 6,000MW of extra power for Ethiopia’s grid and help irrigate 500,000ha of land. “To build the dam, the natural course must be dry,” said a spokesman for the state electricity company, explaining the diversion.

It’s an epic project, with a suitable epic name: the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam.

The water that will fill this dam and power the hydroelectric plant will come from the Blue Nile, one of the Nile’s two major tributaries. The Blue Nile starts in Ethiopia’s Tana Lake before winding its way into Sudan where it joins the White Nile and continues up through Egypt and into the Mediterranean.

Only one problem: both Egypt and Sudan are relatively dry countries, and neither is happy about the prospect of Ethiopia messing with their water supplies. Egypt and Sudan have two principal concerns: first, that the dam will allow Ethiopia to use much more Nile water, meaning there is less water in the Nile River Basin as a whole (this is of particular concern when the dam is being filled up); and second, that Ethiopia will essentially have the power to turn the Blue Nile on and off, to choose how much water should flow downstream and when it should flow.

In short, both Sudan and Egypt are worried that their water security will be controlled fromAddis Ababa. It’s not a new concern. A treaty signed in 1929 addressed exactly this problem, with colonial-era Britain making sure that the lion’s share of the water (87%) was guaranteed for its prize colony, Egypt, with Sudan getting most of the rest – a situation that remained largely unquestioned until 2011 (bar a few renegotiations over their respective percentages between Egypt and Sudan).

In 2011 Ethiopia revealed the plans for its new dam, and started recruiting some of the other Nilotic countries into an alliance to challenge the status quo. A treaty, the Nile Cooperative Framework Agreement, was signed between Ethiopia, Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda, with the explicit purpose of renegotiating how the Nile water was apportioned.

Egypt, with the most to lose, was scared of the impact of any dramatic drop in Nile water supply. “In short, it would lead to political, economic and social instability,”said former Egyptian water minister Mohamed Nasr El Din Allam. “Millions of people would go hungry. There would be water shortages everywhere. It’s huge.” But Egypt was also occupied with a little thing called the Arab Spring, a situation which Ethiopia leveraged to its full advantage (announcing even more ambitious plans for the dam just a few days after Hosni Mubarak resigned, for example).

As Egypt has calmed down, the government has been able to give more attention to the looming Nile problem. Aware that it is in no position to physically secure the source of the Blue Nile, which would require a full-scale invasion of Ethiopia, it has toned down its critical rhetoric and stressed the need to cooperate. Most importantly, Egypt has acknowledged that Nile water needs to be shared more equitably, and that a conflict over water is the last thing anyone needs.

“Our concern is for it not to affect our water security, to harm the water coming to Egypt. How to do it effectively on the ground and how to implement it, this is something to be left to the technicians to discuss and agree on,” said Mohamed Edrees, Egypt’s ambassador to Ethiopia, speaking to Bloomberg. Sudan, meanwhile, has said publicly that “we don’t have any problems with what Ethiopia has done” – a white lie, sure, but one that reflects everyone’s wishes to keep tensions to a minimum.

Both countries have also realised, perhaps, that the hydroelectric function of the dam – probably the most important as far as Ethiopia is concerned – will only work as long as water keeps flowing through the river, meaning that Ethiopia too would suffer if it ever did decide to turn off the taps. “No flow through the turbines and down the river will mean no electricity for Ethiopia so it’s a win-win,” Mike Muller, former director-general of South Africa’s Department of Water Affairs, told the Daily Maverick. “There will be some reductions in flow while the reservoir fills, but this could be managed with minimal impact if there is cooperation between the countries.”

Ethiopia, for its part, has been doing its utmost to convince Egypt and Sudan that it has no intention of threatening their water supply. “We are not selfish, we are not only looking at our national interest,” said deputy prime minister Debretsion Gebremichael, who is also chairman of the state-owned Ethiopian Electric Power Corporation, speaking to Bloomberg. “This is an international river and we will try our best to accommodate their benefits and their interests.”

This is good, calm talk from all three countries, all of which have all now realised that although the situation must change, it can and must be managed so that no country suffers unduly. As Muller explained: “What is at issue is the validity of old colonial agreements which prioritised water for Egypt over just about any development in the upstream countries. The sooner that nettle is grasped, the better for all concerned. There is no future for Egypt in continued conflict and they know that they must use the water available more efficiently to allow upstream countries to develop their agriculture. If all parties act sensibly, the construction of the dam in Ethiopia could trigger a new era of cooperation.” DM

Read more:

- Ethiopia diverts the Nile, alarming countries downstream on the National

Photo: A computer rendering of the dam.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider