Maverick Life

The house that slavery built gets a new home in Smithsonian

The newest of the Smithsonian Institution’s great museums in America, the National Museum of African American History and Culture, is planned for completion in 2015. A centrepiece of this building will be an authentic slave cabin from South Carolina. J BROOKS SPECTOR looks at the larger significance of the acquisition.

Three decades ago, while living in the East Java city of Surabaya, we read a particularly astonishing letter in the Indonesian news weekly magazine, Tempo (closely patterned after Time magazine). The letter was from a Malay South African who owned a generations-old copy of the Koran and an elaborately engraved kris – an Indonesian ceremonial dagger, the kind with a wavy blade made from the repeated hammering and shaping of meteoric-origin iron treated with arsenic and then highly polished.

The two precious heirlooms had been handed down to him through hundreds of years, back from a time when an East Indian prince who was his long-ago ancestor from the Island of Tidore (one of the clove growing Spice Islands fought over by the Dutch and Portuguese) had been captured by the Dutch East Indies Company, the VOC, and then exiled into a life of slavery, back in Cape Town’s early days. Many such people were forcibly taken to the Cape from what is now Indonesia. There they helped create the trademark architecture and design sensibility of the Cape – a tantalising mixture of European, Chinese, Southeast Asian and even Arabic styles.

The Cape Town letter writer had hopes of somehow, some way, reuniting these heirloom objects with any surviving distant relations of his family. He was reaching out to connect with people who might also be descendants of the man who had been carried shipboard from the East Indies to Cape Town and exile and slavery more than 300 years earlier.

This need to reach across the centuries and connect seems a persistent urge among us all – and it becomes something even more compelling when slavery is added to the mix. During the holiday of Pesach, Jews everywhere recall the slavery of ancestors in Egypt. The Sidi can still draw upon bits of oral history about being brought to the Indian subcontinent – most often as slaves – across from Northeast Africa half a millennium ago. And, of course, people of African descent living from North to South America immediately understand their historic ties to the Atlantic slave trade and Africa at each look in a mirror.

But for decades, centuries even, save for half-remembered family stories, most African Americans could only trace their origin stories back to the saga of slavery in the Deep South. Sometimes there were rumours of partly Native American origins or about light-skinned relatives who had as passed as whites, or still other presumed connections to well connected white family trees. But, for most African Americans, certain knowledge usually began with the movement away from hardscrabble lives in the South, and then northwards in “The Great Migration” that began in the second decade of the 20th century to the great cities of the Midwest and Northeast.

But it took the 1977 American television mini-series, Roots, based on writer Alex Haley’s book by the same name, in which Haley had, astonishingly, traced part of his ancestry back to an 18th century Mandinka boy, Kunta Kinte, who had been sold into slavery from a village in what is now Gambia to make the connection whole. Many millions of Americans – black and white – watched, transfixed, episode-by-episode, with the dramatic unravelling of what was generally thought to be the unknowable, lost-to-time-history of African Americans, right back to Africa itself.

In many ways, Haley’s ultimately successful odyssey, brought into every home by television, triggered a great wave of interest in African American genealogy. This joined together with the continuing growth in Black/African American Studies in US universities. And now, more recently, this interest has even drawn strength from discoveries in paleoarchaeology and the exploration of the “African Eve” origins story – advances in genetics married with studies of the fossil record.

Along the way, the pressure has been growing to provide much more evidence of the authentic, central African American role in American history more generally. Historic colonial Williamsburg, the capital of Virginia during the Revolutionary War and a tourist destination that has drawn upwards of a million people a year to experience its living history exhibitions, has added the reality of slavery as part of its historical re-enactors’ work and increasingly woven the documentation of slavery – and slaves – into its depiction of American colonial life. Historic plantations in the South – including Mount Vernon, home of first president George Washington – have made similar course corrections away from an anodyne, Gone With The Wind-style depiction of slavery and towards something approaching an effort to encompass the enormity of the crime.

Perhaps the culmination of this movement now comes with the establishment of what will almost certainly be the final Smithsonian Institution museum on the Mall in downtown Washington, DC. As many people began to say some years ago, well, there is a museum dedicated to modern art, to the Native American, to African art, to Asian art, to technology and aerospace – 16 separate facilities in and around Washington and two in New York City – but where was the history of the African American?

And so, after years of discussion, the new National Museum of African American History and Culture is planned for completion in 2015 as a complement to all the other museums between the Washington Monument and the US Capitol. While the Smithsonian as a whole has thousands of items relevant to the African American experience in its vast collections, until this museum was proposed, planned, funded and then construction began, such materials had had no one central home base.

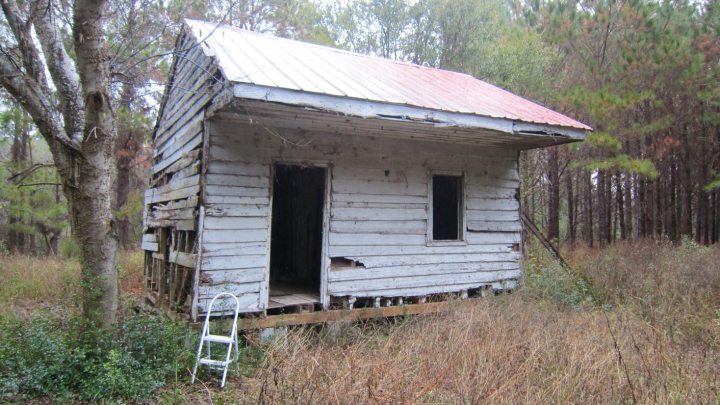

One obvious theme – perhaps the most obvious of all in depicting the earlier history of African American life in the country – was, of course, slavery, “that peculiar institution” as it was so euphemistically called. While any display on slavery would never be able to duplicate the actual personal humiliations and degradations inflicted upon millions over 250 years, curators and display designers clearly determined that at least one object was an iconic item around which they had to build all the others – an actual slave cabin from an actual plantation. Not a replica, not an imitation, the real deal. And so the curators came to Point of Pines Plantation, on Edisto Island, South Carolina, to find a verified antebellum slave cabin that – once it was moved to downtown Washington – would as graphically as possible depict the real life circumstances of slaves.

While the ravages of time, mildew and hungry termites had treated the building very badly, nevertheless, it was still one of the country’s oldest extant slave cabins and it clearly dated back to the 1850s. Amazingly, black families had lived in this building and others like it – two-roomed shacks without electricity or heating – until the 1980s.

Once it has been dismantled, moved to Washington and then restored and reassembled, it will become one of the new museum’s most important artefacts, joining such items as the shawl from 1850s Underground Railroad organiser Harriet Tubman, slave rebellion leader Nat Turner’s personal Bible, an actual fighter aircraft from the World War II all-black bomber escort formation, the Tuskegee Airmen, and Emmett Till’s coffin. Till became a martyr to racial injustice when he was tried, convicted and then killed over trumped up charges of flirting with a white girl.

In making the announcement of the acquisition of the cabin, Lonnie Bunch, the new museum’s director, called the cabin “a true jewel in the crown of our collection. Slavery is the last great unmentionable in public discourse. But this cabin gives an opportunity to come face to face with the reality of slavery. It humanises slavery.”

This cabin had already been on the National Register of Historic Places since 1986 and local historians had tried to save it from destruction. Three years ago, the plantation’s current owners had donated the actual cabin to the Edisto Historical Preservation Society, but not the land it stood on, however.

In describing the cabin, the Washington Post notes, “Slave cabins are not rare — many are still on sites that were formerly plantations in Southern states. But the location of this cabin tells an unusual story of slavery and freedom. The cabin was on a cotton plantation that was abandoned during the Civil War, and many of the slaves liberated themselves after the Union Army occupied the island. Bunch says the cabin’s history is one reason museum officials selected it as a signature piece in the collection.”

The local preservation society had raised nearly R400,000 to remove choking vegetation and install stabilising bars to steady the collapsing building, but it never had sufficient funds to move the building to a new and more secure location. By the time the Smithsonian called on them, Gretchen Smith, the local preservation society’s director, said, “Honestly, we were about to give up.”

The Smithsonian exhibition curator, Nancy Bercaw, says this cabin is the perfect item for the Smithsonian. The cabin needed a new home and because people had lived in it for years long after the end of slavery, the museum can position it in an exhibition that transcends slavery itself and carries on into the post-Civil War period. Bercaw adds, “The Sea Island [those isolated, sandy coastal places where the West African languages-influenced Gullah dialect often held sway] history is so rich and multigenerational. This history has been tucked away. It hasn’t always been safe to pull out these stories.”

Last week, a crew from a historical preservation company began taking the cabin apart and carefully labelling the locations of each part. The more modern bits like the current tin roof and metal nails holding it together will be replaced with authentic period materials instead. In the process of taking the cabin apart, the team found decades-old newspapers stuffed into the walls for a bit of insulation and even discovered remnants of blue paint on the door and window frames. Historians now believe slaves imported from Caribbean islands may have painted them that way to ward off demons.

While the precise age of this cabin is not known, an 1851 map of the plantation showed the cabin already at its present site and an 1854 plantation inventory of its property listed some 75 people resident there as slaves. While 80-year-old Junior Meggett didn’t live in that particular cabin, he did grow up in an identical one located nearby and he told reporters that in winter, the nights were so cold everyone huddled around the stone fireplace so they could sleep. Meanwhile, summers were so infested by mosquitoes inhabitants had to keep a fire going, despite the heat, to keep the insects away with the smoke from the fire. He added that this plantation was “a tough place to live. But we didn’t have any choice. It was just where you lived.”

The totality of the African American historical experience, like South Africa’s own history of slavery (although it had ended here some three decades before emancipation came in the US), still remains a fraught topic for many people to discuss openly. For many, it continues to be tied up with arguments about the circumstances of contemporary race relations and discussions of current urban social pathologies.

But, as Bunch explains, “The cabin allows us to humanise slavery, to personalise the life of the enslaved, and frame this story as one that has shaped us all. [Slavery] is not just an African American story. Slavery was the dominant institution in America — it coloured religion, it coloured politics and it coloured expansion. It was an economic engine for both northern and southern prosperity. By not talking about it, we neglect a great understanding of who we are.”

The Smithsonian is clearly banking on the idea that as the millions of school children, domestic tourists and foreign visitors descend on this newest addition to the Smithsonian’s collection of museums, this cabin and the other exhibitions clustered around will go a long way towards making the tangible reality of slavery – and so much else – that much more accessible to its visitors. And with that access will come comprehension – and then greater understanding. DM

Read more:

- Haunting Relic of History, Slave Cabin Gets a Museum Home in Washington at the New York Times

- Antebellum slave cabin in S.C. to be restored for African American History Museum at the Washington Post

- SC slave cabin dismantled to be transported, rebuilt for display at coming DC museum at the Washington Post

- About Us – The National Museum of African American History and Culture at the Smithsonian Institution’s website

- Slavery in America at History.com

- The Roots of Slavery at the BBC website

- Did Black People Own Slaves? – an article by Prof. Henry Louis Gates at The Root.com (a comprehensive website on African American topics)

- Slave Quarters at the Mount Vernon website (Mount Vernon is George Washington’s home)

- Societies after slavery: a select annotated bibliography of printed sources on Cuba, Brazil, British colonial Africa, South Africa, and the British West Indies at the University of Pittsburgh Press Digital Editions website

Photo courtesy of The National Museum of African American History and Culture

Become an Insider

Become an Insider