World

Venezuela: Chavez-lite Maduro’s disputed win

Following the death of President Hugo Chavez, the very public demonstrations of loss by his many supporters, and, then, after a short, bitter campaign for the remainder of his six-year term of office, Chavez’s political heir and loyal deputy, Nicolas Maduro of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela, eked out a narrow victory over his opponent, Henrique Capriles. Maduro’s margin of victory stood at 234,935 votes, with nearly all votes now counted. This means a 50.7% - 49.1% split, in an election where about 78% of eligible Venezuelans cast their ballots. Maduro’s task is to somehow continue Chavez’s policies in the face of a worsening economic climate in Venezuela. By J BROOKS SPECTOR.

Maduro is a former union leader and bus driver – and his political allegiance is firmly rooted in the more radical wing of Chavez’s party. Maduro has close ties to Cuba – and especially the Castro family. Chavez had named his 50-year-old vice-president and foreign minister, Nicolas Maduro, as his preferred successor when his cancer recurred and Maduro apparently was one of the few who had comprehensive knowledge of Chavez’s condition as it worsened.

Given that Chavez had beaten Capriles in Venezuela’s previous presidential election in 2012 by well over 10 percentage points, it seems the old Chavez charisma, electricity and magic was ultimately worth about 11 percentage points in an election. The results of this most recent election – sans Chavez – reveal a nation sharply divided over the import of Chavez’s legacy.

When the presidential campaign began, Maduro had been expected to cruise to victory, given all those widespread expressions of grief over Chavez’s death. In his campaign, Maduro repeatedly and enthusiastically promised to continue Chavez’s so-called “Bolivarian revolution”. But with the country’s now-chronic inflation, crumbling infrastructure, growing power outages, and consumer goods shortages, it seems Venezuela’s political realities may have virtually caught up with Maduro by the day voting took place. In the end, he barely squeaked out a 1.6% margin of victory over his opponent. Nevertheless, putting on his best, brave face, Maduro duly claimed his victory, saying his predecessor’s revolution “continues to be invincible”.

Maduro’s victory came after a confrontational, mudslinging campaign. While Maduro had promised to carry on Chavez’s legacy, the message of Capriles was starkly different: Chavez had put the nation – a country with some of the world’s largest oil reserves – squarely on the road to ruin. Capriles, an athletic 40-year-old state governor, had publicly mocked and belittled his opponent as a poor-quality, bland imitation of the charismatic, spellbinding deceased president. His primary campaign message had been a relentless focus on “the incompetence of the state”. At rallies, Capriles repeatedly read out lists of stalled road, bridge and rail projects and he then turned to audiences to ask them to remember all the staples now in scarce supply on store shelves. Capriles made his near-win despite Maduro’s party’s near monopoly on radio and television broadcasting and the party’s use of the state’s machinery to mobilise voters.

Throughout the short campaign, Capriles had given Maduro very little of the respect he had previously given Hugo Chavez in their earlier contests. In what seems to have been a desperate move, Maduro tried to tar his opponent as a kind of fascist, calling Capriles backers “the heirs of Hitler”, an odd, off-pitch accusation, given that the 40-year-old Capriles is the grandson of Polish Holocaust survivors.

Photo: Venezuela’s opposition leader Henrique Capriles gestures during a news conference in Caracas April 15, 2013. Capriles refused on Monday to accept ruling party candidate Nicolas Maduro’s narrow election victory and demanded a recount. REUTERS/Marco Bello

Given the razor-sharp margin by the end of Venezuela’s election day, Capriles was still in a defiant, no-surrender pose. He was calling for a recount of the entire vote, saying his own campaign had “a result that is different from the results announced today”. And then, addressing Maduro and his claim of victory, Capriles put on his own brave face, saying, “The big loser today is you – you and what you represent… The people don’t love you.”

For his part, Maduro said he was open to an audit of the voting. But the head of Venezuela’s electoral council said the outcome of the country’s vote already was a done deal. It was by “the irreversible results that the Venezuelan people have decided with this electoral process,” he announced. Venezuela’s electronic voting system is now completely digitalised, but generates a paper receipt for each vote as well. This actually makes a full vote-by-vote recount possible.

Following the narrow victory, many in Maduro’s own camp seem distinctly underwhelmed by his victory margin and stung by their candidate’s barely successful race for Venezuela’s presidency. “The results oblige us to make a profound self-criticism. It’s contradictory that the poor sectors of the population vote for their long-time exploiters,” tweeted Diosdado Cabello, national assembly president. Cabello is, not surprisingly, a rival for the Chavez legacy.

Maduro had earlier become Venezuela’s acting president when Hugo Chavez died on 5 March and he had apparently been holding onto a double-digit lead in the campaign, only a fortnight ago. But that lead melted away to his eventual narrow margin by the day of voting. Maduro, a long-time foreign minister and then vice president in Chavez’s administration, had initially ridden the wave of sympathy for the fallen president. He had then pinned his hopes on the immense loyalty for his superior that existed among the millions of poorer Venezuelans who had benefited from government largesse, as well as the machinery of the state that Chavez had put to work in the service of his political party and his presidency.

Once the results were public, Maduro (well, effectively Chavez) supporters set off fireworks and drove around the downtown streets of the capital, blowing their motor vehicle horns in celebration. But analysts were already labelling the paper-thin lead disastrous for Maduro’s chances of being about to continue the full range of Chavez’s policies.

Forestalling a possible military intervention (the bane of so much of Latin America’s history and politics), the joint chief of the Venezuelan armed forces, General Wilmer Barrientos, publicly called on the country’s military to accept the results. A Capriles campaign staffer had anonymously told media that Capriles had met with the military high command once the polls closed, although campaign official Armando Briquet later denied there had been such a meeting.

In his victory speech, Maduro claimed Capriles had called him before the results were announced to suggest a “pact” but that he had rebuffed the suggestion. While the Capriles camp wouldn’t comment on this claim, Capriles began his own not-quite-a-concession-speech declaring he doesn’t “make pacts with lies or corruption”.

As far as Chavez’s legacy is concerned, it is true millions of Venezuelans were moved beyond the country’s poverty line during Chavez’s time as president (although many observers note that there was a more general rise from poverty across many other Latin American states over the same period in conjunction with the long cycle commodity boom). However many observers also argue Chavez’s government squandered a serious amount of the $1 trillion in oil revenues accumulated during his 14-year rule. Chavez’s critics have also argued much of the petroleum wealth was effectively plundered rather than put to use efficiently on behalf of the entire nation.

Cynthia Arnson, director of the Woodrow Wilson Center’s Latin American programme, in writing about Chavez’s legacy, said, “During his 14 years as president, Chavez dominated virtually every aspect of political life. Through lavish social spending financed by the high price of oil (Venezuela has the largest proven oil reserves in the world), and through the sheer force of his charismatic personality, Chavez assembled a loyal base of supporters among those who received not only concrete material and political benefits but also something more ephemeral – dignity.”

“At the same time, and abetted by the fragmentation and, at times, abstentionism of the opposition, Chavez buttressed his dominance through the gutting of institutions such as the judiciary that provide checks and balances against unfettered executive power. He ensured the loyalty of the armed forces through successive purges and likewise stacked the state oil company, PdVSA, with loyalists following a failed strike in 2002.”

However, at this point, despite the nation’s continuing oil wealth, Venezuelans are increasingly at the mercy of chronic electric power outages, crumbling infrastructure, a growing array of unfinished public works projects, double-digit inflation, shortages in food and medicine, and a serious crime wave. In fact, Venezuela now endures one of the world’s highest homicide and kidnapping rates – and one element of Capriles’s campaign for the presidency was, in fact, the argument that these woeful numbers actually became worse once Chavez headed to Cuba last December for his final surgery. With the current stagnation in oil revenue growth, there is little likelihood of any real turnaround under the new Maduro administration.

Across the economy, Venezuela’s current $30 billion fiscal deficit is 10% of the country’s gross domestic product. Many factories are operating at levels of half capacity because the country’s tough currency controls are making it difficult to pay for needed imported parts and raw materials. Business leaders are increasingly complaining major companies are teetering on the edge of bankruptcy because they cannot extend their lines of credit with foreign suppliers. (Chavez had imposed currency controls some 10 years earlier in an effort to halt capital flight when his government began expropriating extensive land holdings and businesses.) In fact, at this point, a dollar sells for three times the official exchange rate with the country’s currency, the bolivar, on the black market. And Maduro has already devalued the official rate of Venezuela’s currency twice this year alone.

The Washington Office on Latin America think tank’s David Smilde commented Maduro has probably gained a pyrrhic victory, as “it will make people in his coalition think that perhaps he is not the one to lead the revolution forward.” And Amherst College political scientist Javier Corrales adds, “This is a result in which the ‘official winner’ appears as the biggest loser. The ‘official loser’ – the opposition – emerges even stronger than it did six months ago. These are very delicate situations in any political system, especially when there is so much mistrust of institutions.” Corrales adds, Maduro has “a penchant for blaming everything on his ‘adversaries’ – capitalism, imperialism, the bourgeoisie, the oligarchs – so it is hard to figure how exactly he would address any policy challenge other than taking a tough line against his adversaries.”

Still, Latin American history professor Miguel Tinker Salas at Pomona College, argues, “Despite the image of Chavez that is typically portrayed in the media, hundreds of thousands of people waited countless hours to see his body lying in state at the Military Academy in Caracas. Those mourners were real people, expressing real pain at the loss of a president they had supported. They were not people who flocked to pay respects because they received ‘free gifts’ as is often suggested by the opposition. Their presence at the memorial highlights the extent to which new social actors – especially women, Afro-Venezuelans, urban social movements, youth, and others – see themselves as active stakeholders in the political process and whatever future course it takes.”

Still, despite that presumably dour future for Nicolas Maduro’s incoming administration, Michael Shifter, president of Inter-American Dialogue, argued Chavez’s influence will not easily disappear. Shifter wrote recently, “Whatever the results of Sunday’s elections, Chavismo will not disappear any time soon. Though it lacks a solid, coherent structure, the movement created and inspired by Hugo Chavez tapped into a sensibility among many Venezuelans that is bound to continue in some form. Absent Chavez, chavismo may be diminished, and will manifest itself in different ways, under a variety of political figures.”

However, as far as Maduro’s usually strident criticism of the United States, there are signs of a shift in that heretofore-brittle, acrimonious relationship. This past weekend, even before his election, Maduro sent a message to Washington he was ready to change the direction of the relationship. Bill Richardson, the former New Mexico governor, who had been in Caracas for a meeting of the Organization of American States, told reporters Maduro had spoken with him after a meeting of election observers to say, “We want to improve the relationship with the US, regularise the relationship.”

Still, despite a possible shift to the less acrid in American-Venezuelan ties, the big question domestically for Venezuela is whether Chavez’s political heir can successfully hold that movement together without the charismatic former leader’s emotional motor and political ardour. Observers now believe Venezuela’s growing economic difficulties as well as Hugo Chavez’s death have left both a gaping hole at the heart of Venezuelan politics – and a huge challenge for Maduro’s political success. DM

Read more:

- In Venezuela, Will ‘Chavismo’ Last Without Hugo Chavez? at the Brookings Institution website

- Chavez’s heir to take over divided Venezuela at the AP

- Chavez heir Maduro wins Venezuela presidential election at the BBC website

- Profile: Nicolas Maduro at the BBC website

- Venezuela Gives Chávez Protégé Narrow Victory at the New York Times

- Nicolas Maduro narrowly wins presidential election in Venezuela at the Washington Post

- Nicolás Maduro declared Venezuela election winner by thin margin at the Guardian (UK)

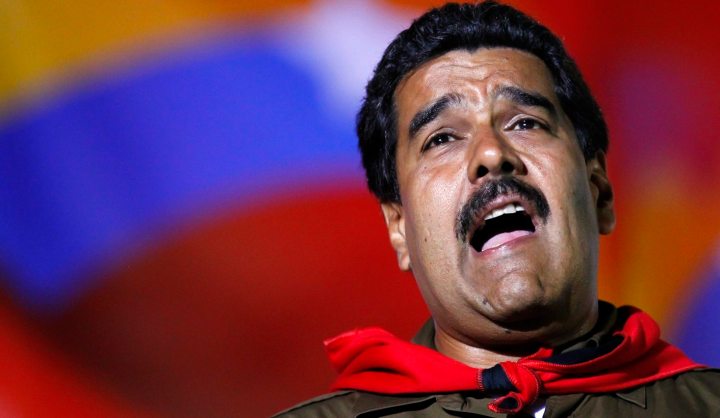

Photo: Venezuela’s acting President and presidential candidate Nicolas Maduro sings during a campaign rally in Caracas April 5, 2013. Maduro said on Friday that Venezuelan authorities have arrested several people suspected of plotting to sabotage one of his campaign rallies before an April 14 election by cutting the power. REUTERS/Carlos Garcia Rawlins

Become an Insider

Become an Insider