Maverick Life

Tretchikoff, stranger in his home town

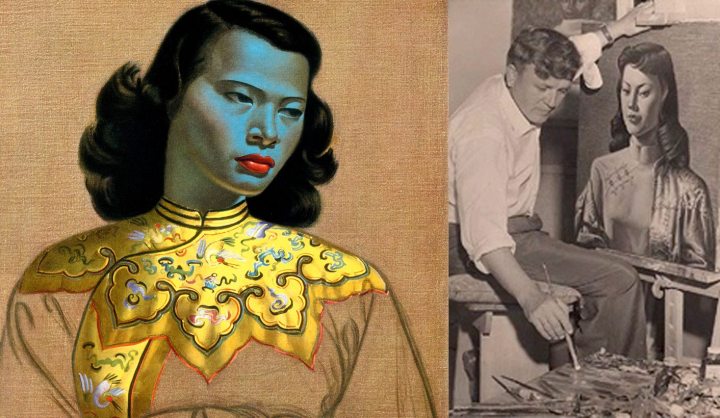

Vladimir Tretchikoff, whose painting Chinese Girl fetched close to £1 million at auction in London on Wednesday, is known the world over. But not in his native country. By BORIS GORELIK.

In a way, Tretchikoff’s career resembles the story of Rodriguez of Searching for Sugarman fame. At the peak of his success, nobody had heard of him in his native country. But while the American singer and his works have eventually been rediscovered by his compatriots, Vladimir Tretchikoff remains virtually unknown in the former Soviet Union.

The creator (some would say “perpetrator”) of the Chinese Girl and dozens of other pictures whose reproductions sold by the hundreds of thousands in the UK, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand and continental Europe, was born in present-day Kazakhstan, then part of the Russian Empire. His native town Petropavlovsk was a major centre of cattle trade. In 1919, during the Civil War, the Tretchikoff family fled to the remotest Far Eastern province of Russia. When Vladimir was about five years old, they crossed the border into China. He never returned to the country of his birth, even after the demise of the communist regime.

I visited Petropavlovsk in 2010 only to discover that even the director of the local arts museum had never seen his works. In this friendly Eurasian town, historians learnt about Tretchikoff only from his obituaries.

Perhaps the only Soviet journalist who met Tretchikoff during the Cold War was Vitaly Korotich. (Korotich is best remembered as editor-in-chief of Ogonyok, the most daring magazine of the Gorbachev era.) In 1965, he travelled to Toronto and saw an advertisement for the exhibition of a Russian artist at Eaton’s department store. He went inside. To Korotich’s dismay, the artist was not so much showing the works as selling them. He described Tretchikoff as “short, blond with a pencil in his right hand standing at the counter, one of the hundreds of counters at the enormous Eaton’s.”

In the 1950-60s, Tretchikoff pictures were mainstays of the British top 10 best-selling prints, but they weren’t available in the USSR. They could not possibly be endorsed by Soviet authorities. Apart from the fact that he was an émigré, which to them was equal to being a renegade, the manner in which he painted, his treatment of his subjects, ran counter to the main principles of “social realism”.

Christine Lindey, the author of a pioneering comparative study of official and unofficial art on both sides of the Iron Curtain, notes that while Tretchikoff showed “the noble savage in the timeless bush”, his Soviet counterparts depicted Africans as using modern facilities or fighting for freedom. Tretchikoff’s Chinese Girl was mystical, whereas Asian women depicted in official art from the USSR were active and resolute. Even when the subject and the realistic style of the work by Tretchikoff and Soviet artists were similar, the content and the message could not have been more different.

Soviet officials in charge of cultural affairs could make exception for émigré artists of the stature of Marc Chagall, who exhibited in Moscow. But Tretchikoff, the bane of art critics, wasn’t one of them.

Despite that, the Chinese Girl made it through the Iron Curtain. John Miller, a former Moscow correspondent for the Daily Telegraph, says that the Ministry of Works in London supplied reproductions of what art critics disparagingly called the “Green Lady” to British diplomats working in the USSR in the 1960s. In his memoirs, he tells how they used the pictures to cover listening devices planted by the Soviets in their homes. Removing the bugs was pointless: nobody would know where they would be hidden next. So the diplomats tolerated the nuisance – with the help of a Tretchikoff or two.

On the other side of the planet, in America, Tretchikoff wasn’t particularly popular either. After his triumphant tour of the US in 1953-54, when he wrote off the Chinese Girl during his show at Marshall Field’s, he was largely forgotten. His prints could be found in the picture sections of department stores but they never sold in the huge numbers they did in South Africa, Britain or even neighbouring Canada.

So it’s hardly surprising that the lady who bought Chinese Girl in the Chicago-based department store was hardly aware of its fame. “Some years after I purchased the original,” says Mrs Buehler, “I heard that Tretchikoff had a reputation outside of America as a ‘King of Kitsch’. Perhaps I saw an article at some point. But I never pursued it. And I had nothing to do with all these reproductions. That was his doing.”

In the 1970s, Buehler gave the Chinese Girl to her daughter who took it along as she changed flats and houses. “I held on to her because she was gorgeous. She was in the family for a very long time, and my mother and grandmother loved her,” says Mrs Buehler’s daughter. “So she stayed with me even though she was putting off some of my roommates. That’s why she hung either in my bedroom or my office.”

When she lived in Arizona, she was burgled twice but the thieves never took the painting.

“I knew the Chinese Girl had some history but I didn’t know much about it’, she continues. I kept her because it was something that I treasured. When I was in college in the late 70s, I saw it in a daytime TV drama. And I said: ‘Oh, my gosh! That’s my painting!’”

Only in 2011, when she was approached by the organisers of the first Tretchikoff retrospective, at the South African National Gallery, did she realise how important her picture really was.

During the retrospective, the general public got the chance to see the original “Green Lady” for the first time in almost 60 years. And this February, the Chinese Girl briefly returned to South Africa – for a special preview in Johannesburg before the London sale.

Perhaps the finale of the Rodriguez story won’t be repeated in Tretchikoff’s case. I doubt that even the high-profile Bonhams sale would prompt Russians or Americans to rediscover this artist. In the Commonwealth, the “Green Lady” was an integral part of the visual culture of the 1950-60s. Tretchikoff’s pictures have been very closely associated with that period and the nostalgia around it in countries like Britain and South Africa. But not elsewhere.

Then again, you never know. The ebbs and flows of interest in Tretchikoff’s work have been so unpredictable that anything might happen. DM

Boris Gorelik is a writer from Moscow, Russia. His book Incredible Tretchikoff, the first complete biography of the artist, is being published by Tafelberg. It will be available in South African bookshops from 27 May.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider