Maverick Life

John Kani: Still challenging our conspiracies of silence

Forty years after John Kani, Winston Ntshona and Athol Fugard first collaborated to shape a preliminary sketch that eventually blossomed into an internationally acclaimed drama, The Island remains as relevant as ever it was during Apartheid. That’s because it still speaks truth to power, Market Theatre institution John Kani and the director of the latest incarnation of the play, tells J BROOKS SPECTOR over lunch.

John Kani, the internationally acclaimed actor, joins us for a near-Spartan lunch – a bowl of vegetable soup and some freshly baked bread – at the Market Theatre’s Gramadoelas Restaurant. He’s in a relaxed mood now that The Island is finally truly launched into its run at the theatre. It’s not that he was worried about the play itself; after all, he’s been involved with it for 40 years. But any new production of any play always has unique revelations, mysteries and challenges. At nearly 70 years old, very little can still be expected to surprise him; but still, one never really knows about a play until the thing is fully on the boards and going on every night.

Back when the Serpent Players was still a young, experimental theatre group operating in and around Port Elizabeth on the fringes of legality; working in close collaboration with Winston Ntshona and Athol Fugard, the three men workshopped, rehearsed, shaped, cut, trimmed and added to a preliminary sketch that eventually blossomed into the internationally acclaimed drama, The Island. The play was a dangerous, even subversive thing, back in 1973. It remains a fascinating, hard-edged story about the telling of truth to power – drawing its impetus both from the specifics of the South African experience, as well as the universal message in Sophocles’ narrative of Antigone – the Greek drama that is the irreducible, hard kernel that is inside The Island.

The play had originally evolved out of exercises among a group of actors who wanted to explore what they called the “conspiracy of silence”. Everybody knew about Robben Island, but no one was willing to speak about it directly. Seeing the island from the roads around Table Mountain in Cape Town, made the actors think about this fact – how to tackle it, what stories to tell – all without speaking directly about the specifics of Robben Island itself.

John explains that one of the stories comes from an experience of his uncle in prison. This story goes that his uncle has been moving a wheelbarrow filled with rocks and, overloaded, it tips over. The warder sneers at him, “Ja Kani, you want to run a country, but you can’t even run a bloody wheelbarrow.” Another story comes out of the experiences of another Serpent Players actor, Shark, who never knew his lines in Antigone. Throughout those performances, John Kani explains, he has been forced to be Shark’s prompt through the entire play. And then comes word that Shark is, improbably, doing a one-man version of that very play. These two stories become the seed that eventually blossoms into The Island.

As to why doing this play again is important now, Kani says he realises it is the time, again, to address power, corruption and the other ills that have twisted the dreams of the people who pushed so hard for their liberation. And so, as he contemplates the power of Creon in Antigone and what it meant for Antigone herself, and he thinks about current political behaviour, he said to himself, “This is the time to do The Island.”

Yet another inspiration is the realisation that it is important to impart some knowledge to younger people about the cost that was exacted in reaching the time, now, when it has become easier to speak this kind of truth to power. As an aside, John explains his one addition to the text when he has the character John, in his portrayal of Creon, speak of his “fabulous palaces – and compounds”. Given its reference to Jacob Zuma’s extravagant building project at Nkandla, this slight tweak gets a titter, a laugh, and then finally a deeper guffaw, every time. John is emphatic this play is not about Robben Island, per se. Rather, it is broader, larger and more universal. It is about “the indestructibility of the human spirit, man’s inhumanity to his fellow human beings – and the hell of hope and the hell of despair,” he says.

From today’s vantage point, however, it is easy to forget just how difficult and fraught with danger such an effort was, back in the early 1970s. The full weight of Apartheid-era laws was in force. Even finding a place to rehearse, let alone to perform, was a chore for a theatre company in which blacks and whites participated together. Figuring out what to perform, where to perform, who to perform to all were more than the usual quotidian theatrical and artistic chores. These became something of a life choice for the actors – about how, and how much, to confront the regime, and on what turf to do that.

What became known internationally as South Africa’s “struggle theatre” genre – with such iconic works as The Island and Sizwe Banzi is Dead – was barely a fully thought-through concept back then. The Wits University-connected Workshop 71 and the Space Theatre in Cape Town were in their early days, and the Market wasn’t even in existence yet. Yes, there was also a tradition of black theatre in South Africa in works by playwrights like Gibson Kente, and the impact of the racially mixed group that created King Kong remained a vivid memory for those who had actually seen it; but a body of live theatre work that took direct, unflinching aim at the regime was still something new and dangerous. No one was certain of the effects on performers and audience members (let alone on the government or the world at large).

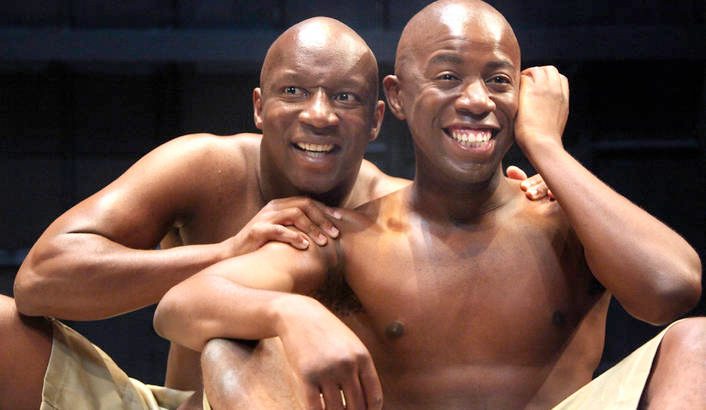

In reaching back to this contemporary classic, John Kani has eagerly embraced some unusual challenges for most directors. He now has four very different relationships to keep in a balance in dealing with the work now on stage. On the one hand, and most obviously, he was a co-creator of the original play. Then, for dozens of years and in productions around the world – including a season that brought a Tony Award for his and Winston Ntshona’s Broadway run, alternating with Sizwe Banzi is Dead – he was the progenitor of the role of “John”. Then there is the obvious fact he has directed this production, rather than appear in it. The play demands a young man and it was time to pass the role along to someone younger. But in doing this, this time around, he has directed his own son, Atandwa, a young actor of real power and gravitas on stage, in the role that the elder Kani had made his own for close to a half century.

As we talk, Kani explains some of the history behind the work. There have actually been two different versions of what is a classic of the South African theatre. This is not totally unknown with dramas, of course. There have been various alternative texts for some Shakespearean plays with modest differences in wording; there are multiple scores and libretti for some classic operas – as well as revised versions with other works. There are even multiple – equally valid – originals of Edward Munch’s The Scream, the uber-painting of 20th-century angst.

However, this information about The Island helps explain a comment Malcolm Purkey, the Market Theatre’s artistic director, made when he saw rehearsals of this production. Purkey said he was startled to realise he felt he was watching a different play from the one he thought he already knew so well, having taught it for decades in the University of the Witwatersrand’s drama programme.

As John explains over our modest lunch, once the three co-authors had finally tuned the basic script for performance, while it was on tour, Kani says Athol Fugard had taken their rough working script, then bent it into a smoother, more polished English – but with spaces where the two actors improved certain bits. Fugard then arranged for it to be published by the Oxford University Press in the UK as the authorised text, together with an edited version of Sizwe Banzi as well as Fugard’s solo work, Statements After an Arrest Under the Immorality Act, all in one volume, itself entitled Statements. And this is the one two generations of South Africans had worked from when acting in it or studying it.

Sometime later, John arranged for his and Winston’s working script – now advanced beyond the already published version – to be issued in America by Viking Press as a more fully-developed, complete, yet still-hard-edged version of the text, drawing it out of a transcription of their Broadway performances. For this current production, Kani is using this “second” version – although it is what he prefers to describe as the genuine version.

And so he is asked how is it to direct one’s own child in a role that the older actor had seemingly defined for all time, and that, to a considerable degree had also defined him? After all, the iconic photographs of the early productions of” show a lithe, muscular, shaven-headed John Kani with anger, frustration and hope glowing in the eyes. And the very names of the two characters in the drama are, after all, John and Winston. John explains that this was a quick, impromptu fall-back decision. Up until just before its initial performances, the co-authors hadn’t actually bothered to name the characters. By the time they began to perform, it seemed too late to pick other names.

In dealing with his son, John insists that on stage, in the rehearsal room, afterwards while going through director’s notes, he is Mr Kani, Mr Director to both Atandwa and co-star, Nat Ramabulana, another fine younger actor, who plays Winston. At home, over dinner, at breakfast, to Atandwa, he’s dad, but said deferentially. But both Kanis are actors, after all; they both know how to take on the mantles for roles that are not, precisely, them in “real” life. But in this production, while he kept the names John and Winston as the two characters’ names, Kani told Nat Ramabulana to use the name of his actual wife, Odwa, when he talks on the pretend telephone so he could discover the pain of his character’s separation more viscerally.

As an aside, considering the many ways The Island has now been done around the world, John recounts seeing a production of The Island in the US in which there is a moment of subtle homosexual overtones (not so rare in prison, after all), when the one prisoner says to the other (who is wearing Antigone’s costume), “It’s your turn tonight”. After a couple of beats, that prisoner then says, “It’s your turn… to call” and the tension is relieved – in John’s mind – about where this particular production of the play is headed. And then there was the Japanese version in which the prisoners must disrobe completely in the presence of the warder and the warder menaces the prisoner with his long bamboo kendo pole. That gets John into talking about the many times when Antigone has been used by theatre groups in very difficult eras throughout history to point at how real “justice has been hidden within the law”. This is something that continues to give The Island its staying power.

Back at the beginning, in the first sustained collaborative effort with Athol Fugard and Winston Ntshona in the Serpent Players that had produced Sizwe Banzi is Dead, Kani had drawn deeply from his own real-life experiences on the shop floor of a Ford assembly plant. This led to the trademark monologue that is funny, angry, world-weary and worldly – and that opens the play. Sizwe Banzi explores the bizarre lengths someone would go to under Apartheid to gain permission to live and work in a city, rather than starve in an impoverished rural homeland. By contrast, rather than simply being workshopped out of funny, poignant situations, The Island drew inspiration from an actual story about the incarceration of two men in a prison they simply called the island.

Throughout his long career, much of Kani’s theatrical work has been controversial. He was once arrested, presumably because of his theatrical attacks on Apartheid. But it was his performances in Strindberg’s Miss Julie and Shakespeare’s Othello in the mid 1980s – in which he kissed white actresses on stage – that became turning points in South African theatre. In the former role, given the lusty verisimilitude of his acting, he even received death threats over his acting. But despite his extensive work in film and with television, as well as on stages around the world, Kani’s reputation remains inextricably tied to his history with the Market Theatre, a national institution he has been involved with, variously on stage, as a director, on the board or as its managing trustee, almost since it opened in 1976.

His first fully solo work, Nothing But the Truth (NBTT), has become a South African phenomenon, at least as much as his highly regarded roles in other Fugard plays – and in some of the classics. NBTT posed the question of who ultimately mattered more in South Africa’s struggle towards non-racial democratic values – a man who had been a political activist and then an exile or his brother who got up every day and went to work, supporting both his own family and that of his brother. NBTT has now had extended runs throughout South Africa and around the world and eventually was turned into a feature film. Kani is now completing work on a new play, this one dealing with the life of a committed exile activist who must confront some fundamental choices when he learns that the political prisoners are actually coming out of their cells – and the end of the Apartheid regime is truly at hand.

John Kani’s impact on South African theatre and culture is extraordinary, but his legacy will only be enhanced as he transfers his sense of the contemporary classics he has acted to the next generation of actors. As we finish lunch and our conversation, Kani says he is contemplating staging Aristophanes’ Lysistrata, but placing it in a war-torn African area. Or, how would it be if he finally tackles King Lear? He says he thinks he’s finally the right age for that role – and it could be an important moment of reflection on the 20th anniversary of South African democracy. Are there any would-be theatre impresarios and underwriters out there? Operators are standing by to take your call. DM

Photo: John Kani’s The Island.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider