Maverick Life

Street Life: The Vermaak brothers – between prison and a hard place

Louis and Coert Vermaak beg and hand out flyers on Johannesburg’s streets. The brothers have been together through prison, homelessness and alcoholism as everything they had, the family, the jobs, the life, has fallen apart. GREG NICOLSON tracks them down to hear their story.

Louis is a walker. From Park Station, where he buys his R2 coffee, to the Wits Bertha Street entrance; from Constitutional Hill to the Wits Jorissen Street entrance; down De Korte Street, up Juta, down Wolmarans, I trace his usual spots. His brother Coert is outside Pick n Pay in Braamfontein where he begs or hands out pamphlets for colleges named after various virtues or American cities offering a wealth of courses on business administration.

Coert sits on a bin with three secondhand books he hopes to pawn. The skin on his face sags in the spaces not covered by his beard and long hair. He doesn’t know where Louis is. I wait. A municipal worker on his lunch hour feeds pap to the pigeons while Wits students pass. Colour blocking, I notice, is still in vogue.

We eventually find Louis sitting against a wall with his head on his knees. A few years younger than Coert, who is 42, Louis’s hair and beard are cropped and his clothes almost belie the fact that he is homeless. His cream chinos are the correct size, but his V-neck jumper opens to reveal his weather-beaten chest.

Both brothers are polite and joke with each other and those who pass. Their conversation is frequently interrupted as one tries to finish the other’s sentences. “My brother, it was tough hey,” says Louis. “It was hard for us. I mean…”

“We grew up hard, it’s true,” interrupts Coert in a slurred drawl.

Louis continues despite the interruption. “Especially as kids and things like that. But we can thank God we are still alive.”

The brothers grew up in Claremont, Johannesburg. Their father died when they were young and their mother struggled to control the family of four boys and two girls.

Exasperated by trying to get the brothers in one place, I force them into the first restaurant I see. Louis is the more open of the two: “You know, ah, mostly I think, aaaah, we, we had a tough life, a hard life, especially growing up without a father, you know, all by the mother, but I’m proud of her,” he says, leaning in and looking me in the eye as he talks. “She raised us up very good. It’s just our ways and things that, ah, make us bad people. You know?”

Claremont came with its scraps. “Boxing, lots of boxing, but not with knives and guns like now,” says Louis. As a boy, he stopped going to school, caused trouble with older friends and would run away from home. At 14-years-old he broke into a neighbour’s house and stole a VCR and was sent to a juvenile correctional school.

“That was rough,” he says, wide-eyed as though he still sees it. “I was the youngest in the boarding school. There were guys that have got beards,” he says touching his own beard. “Hahahahaha! Big ones!”

“Hmmmm,” adds Coert.

Louis thanks the waitress and continues. “I mean, it’s like in jail, if you’re outside then you commit crime then you go into prison. You, if you come out, otherwise you can change or you can go on with that life, and if you go on with that life it’s worse. It’s much… I mean, you start raping, you start murdering, things like that, yeah, so…”

After years in the reformatory, Louis was released and took a welding job. But it wasn’t long before he went back to his old friends and was caught riding in a stolen car (Louis says he didn’t know it was stolen, nor did he steal it). This time he went to Klerksdorp prison.

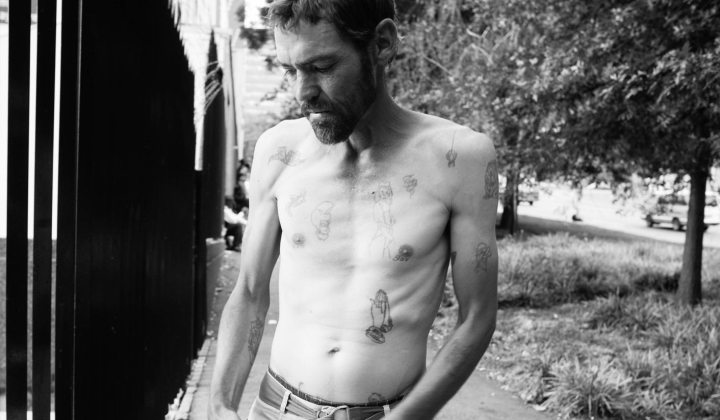

In the streets, he walks with the skulk of someone who knows the dangers of the city, but it is his tattoos that give away his time inside. Even when he’s wearing a long-sleeved shirt you can see the blotched ink of a prison tattoo between his thumb and index finger.

“I ended up there and it just went downhill. Everything went downhill,” says Louis.

“If you’ve got money inside, you’re alright,” says Coert.

“You’re alright,” echoes Louis.

“If you don’t got money…”

“Yho!”

“It’s a tough life.”

“It’s a tough life,” Louis repeats and they both agree.

Louis didn’t have money, but he was a member of a numbers gang. He joined the 26s because he didn’t have to rob people using violence but could outsmart them, he says tapping his head. The role of the 26s is to accumulate wealth and control contraband. Louis says he worked mainly in the holding cells of courts and on prison transport. He would talk to those who had come from the station cells and point out the inmates who looked dangerous, convincing the newcomer to hand over what he had for safekeeping. Other times, he would talk to new inmates, offering the gang’s protection to anyone who had families who he thought would visit often to bring tobacco and other supplies.

As Louis describes the work of the 26s and how he found his niche, Coert interrupts. “Like me also – me I’m a fransman [not affiliated to the prison gangs].”

“He’s nothing, nothing, nothing, nothing,” explains Louis.

“Me, I do my own thing,” says Coert, the older brother asserting his independence. After Louis’s first stint in prison he was released only to get arrested with Coert for taking copper wiring from an abandoned building. Coert refused to join a gang (but he does have a sole Air Force tattoo, the mark of those who try to organise escapes). But he was protected because his brother was a number. They each saw inmates killed with razor blades and knives, but the only people they personally fought with was each other, coming to such heated arguments that other prisoners begged them to shut up.

When asked if the 26s raped other inmates, the preserve of the 28s, Louis said they did. “No, it’s not okay. In the first place, it’s not his job. Twenty-six has his own job. Twenty-eight has his own job. So why a 26? That’s why I don’t believe in a number anymore, because I saw with eyes my own eyes (that 26s were raping prisoners).”

All photos: Louis Vermaak stands on the street where he and his brother Coert slept and shows the tattoos he got as part of the 26s gang in prison. (Greg Nicolson/Daily Maverick)

When they left prison together after two years the Vermaak brothers started to live normal lives. They stayed with their mother who had moved to Bloemhof, in the North West, and Louis got a job welding for a mining company while Coert worked at a garage. Coert got married and his wife gave birth to a girl.

The next steps they describe like a work of the devil, a disastrous act of fate that led them to the streets of Johannesburg. They bought a bottle of brandy and finished it.

“After that it was back to square one,” laments Louis, fidgeting with his hands and touching his beard. The brothers both lost their job because they simply didn’t turn up. Coert got another but was fired twice more. Their mother, at her wit’s end, called the police every time they got drunk, started swearing and fought. Eventually, Coert lost his wife and the house he was living in. Their friends vanished.

When they finally stopped drinking, they caught a train to Johannesburg in 2007 to find work. Their luggage was stolen as soon as they arrived. Louis and Coert slept on a footpath in Braamfontein, opposite a Methodist church that offers bread to the homeless. Surrounded by shit and danger is how they describe their six-month stay on the sloped road. To survive, they collected cardboard boxes for recycling but the game got old when others caught on and they had to travel further and further for less reward.

They now live in a boarding house where they get a bed and a meal for R8 a night, which they cover by begging and handing out pamphlets. Their mother is in an old age home. One of Louis and Coert’s older brothers is disabled after being assaulted one night with bricks and is dependent on others. The other brother suffered a stroke and is also dependent. The husbands of their two sisters won’t let the brothers visit. Louis and Coert intervened when one husband was abusive, while the other thinks they’re a bad influence.

“Our family has fallen apart. In the beginning it was alright, but now… It has fallen apart… We all failed in life. All of our brothers. We could have been far in life. We could have been millionaires,” Louis says honestly. “But it’s the alcohol, you know, mainly it’s the alcohol. Alcohol, it was the big problem.”

They miss their dad, or a dad. They want a small chance so both can start working again with their hands, on construction sites, using welding gear. “I think our main problem now, we never had someone to show us the way, you understand? Like a father, you know? To show us, ‘Look here. Do this,’” says Louis.

They take me to where they slept on the streets. It’s a footpath like any other in Braamfontein, except here dozens of homeless men quietly wait for the church to open and offer them some bread. No one acknowledges them and it is clear the brothers only have each other, from Claremont to prison to Bloemhof and here, to where they argue and joke on the streets of Johannesburg.

“That’s our story. It’s a boring story. Interesting but boring,” laughs Louis, who leaves with Coert to walk into Jozi. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider