Maverick Life

Disgrace: JM Coetzee humiliates himself in Johannesburg. Or does he?

Was it merely the worst convocation speech ever given at the University of Witwatersrand? Or was JM Coetzee playing a postmodern literary parlour game, the rules of which only he understood? RICHARD POPLAK dissects the speech that could ruin a literary reputation.

There is only one way to begin this essay, in which I discuss the recent convocation address given to the University of Witwatersrand graduating class by the man who is inarguably the most celebrated and decorated living English-language author. And that’s by referencing Elizabeth Costello. Costello was the ostensible protagonist in Coetzee’s Life of Animals (1999), and a dowdy deus ex machina in the later novel Slow Man – which is to say nothing of her eponymous outing, published to baffled acclaim in 2003.

But we degrade Costello by calling her a character. She is not Anna Karenina or Harry Potter’s Hermione Granger, but literary postmodernism’s chief whip –policing the dividing line between fiction and meta-fiction with quick snaps of her intellectual rawhide. Just as Coetzee elevated the novel to the height of its postmodern possibilities, Costello started to dissemble it before our very eyes. She is alter ego and imp; philosopher and frump.

So, who was it standing before us on Monday, shortly after 10am, in the Wits Great Hall? Was it Elizabeth Costello, all robed up and prepared to accept an honourary Doctor of Literature degree from university bureaucrats and academics? Or John Maxwell Coetzee, Nobel laureate, Booker darling and lifelong academic himself? If it was the former, we were witness to another of the bolts of brilliance so often dispensed from Costello/Coetzee’s store. If it was the latter, we are in for one of those intellectual meltdowns that mark the end of too many literary careers. Giants decide that they have earned the right to tell it like it is, and end up writing To Jerusalem and Back, or proposing euthanasia booths for the aged. It’s not that they don’t have fair points, these hairy-eared, geriatric Olympians. It’s just that they’ve become too lazy or senile to argue them properly.

According to a the just published biography,J.M. Coetzee: A Life in Writing, by the late John Kannemeyer, Coetzee is not a reclusive, frosty crank, and nor is he the “prince of darkness” Rian Malan conjured for us in a legendary 1990 profile. He is a prankster of the old school, who once engineered dorky, elaborate set pieces that exhibited humour, if not of the Adam Sandler variety. But Coetzee’s mind is not a place that readers, serious or otherwise, are apt to linger. Not for him the 1,000-page one-armed push-ups of an Infinite Jest or the latest Chabon-fest – one line longer, and Disgrace would have caused a suicide epidemic. His mind is cold, and we need it that way. But he is also a contrarian of genuine intellectual rigour, and he likes to play games.

Was Coetzee playing a game at Wits? The essence of his speech was – and believe me, the following is as banal to write as it is to read – that more males need to become teachers at the primary school level. “It is out of your ranks,” read Coetzee, in his mid-Atlantic don’s drawl, “the ranks of graduates in the humanities, the social sciences, and the sciences, that most of the teachers of the future are going to be drawn, and I want to argue that it is not a good thing for education to fall too much in the hands of one sex.”

Mildly inflammatory statements of this sort from men in their 70s are always a bad sign. Coetzee has long been labeled a misogynist, but who hasn’t, really? He has certainly written some unlikable female characters, but he also created Elizabeth Costello, in a clear need to fulfill an exploration of his female id. No, I don’t buy the misogyny rap. In this case, I think of the gender baiting as something of a red herring.

First, a point on the assembled graduates. These were not your pimply undergrads wearing nerd glasses to hide their hangovers, but a cohort of heavy hitters come to collect their philosophy doctorates and their Masters of Management. Their theses ranged from “Distribution change in South African frogs” to “Influence of satellite DNA molecules on severity of cassava begomoviruses and the breakdown of resistance to cassava mosaic disease in Tanzania.” In other words, not the type who were rushing to sign up at the Department of Education, hoping to cash in on that annual R80,000 ($9,500) entry-level salary.

Second, it very quickly became clear that Coetzee was speaking about a public education system that, if it exists anywhere on earth, certainly doesn’t exist in South Africa. (Unless he was recruiting for Eton, in which case, I apologise.) Coetzee’s imagined institutions are full of young minds waiting to be nourished, a copy of Homer’s Iliad or Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain just waiting to be plucked off a shelf, and explained to a klatch of 11-year-olds by a mustache-twirling, safari-suit-wearing alpha male. No doubt, the schools Coetzee was so busy adumbrating have walls, chalk, blackboards and a textbook or two. That he made not one solitary reference to the education crisis currently destroying another generation of South African youth – a crisis President Jacob Zuma blithely blames on the architect of Apartheid, Hendrik Verwoerd – was, at best, pathologically out of touch. That the noisy activist group Section 27 have moved away from Aids and turned to school toilets – there are kids that can’t take a crap in South African schools without getting more of the same all over their shoes, should they own a pair – sums things up succinctly.

Next up was some blather on how men and women possess different qualities, and how being educated by both can lead to a fuller experience, all presented in gentle tones that implied a revelatory insight. He expressed regret at how the education field has come to be dominated by women, and assured the young men in the audience, of which there were none, that a life as an accountant or a graphic designer meant a lifetime of working with assholes. (I’m paraphrasing here.) Then: “Well, if you work with young children, I promise you will never have that feeling. Children can be exhausting, they can be irritating, but they are never anything but their full human selves. There is a nakedness to experience in the classroom that you will not encounter in the world of adult work. Now and again teachers find the nakedness of that experience so demanding that they erect screens between themselves and the children.”

Now, Coetzee once admonished Rian Malan, who was pestering him about his novel Foe, by saying, “I would not wish to deny you your reading.” So, I gingerly nudge your eye to the above paragraph, and ask you to acknowledge the repetition of “nakedness,” followed by the verb “erect”. Which, penned by an ingrate, would be worthy of a raised eyebrow, even if it were not followed by this: “It will be good for you to work with children and it will be good for society in general, particularly at this time in history when men who enjoy being with children are suddenly under so much suspicion. I put the case as strongly as I can: it is as much your right to undertake a career teaching young children, if you so choose, as it is your right, in a free country, to prepare for any other career – otherwise what is freedom worth? If a man decides that working with children, teaching children, being among children is more fulfilling than working with adults, then in my view he should be applauded and assisted on his way, rather than being treated as a potential abuser of the innocence of his charges.”

I know, right? This is some Humbert Humbert shit – a literary creation Coetzee kens so well that he could probably recite second-rate Latvian translations of his legendary monologue backwards.

A game? A jape? A joke? Perhaps. Whatever it was, it was not over yet. We then swiveled deftly into an area of major concern for the high-end academic – school bureaucracy. “At the bottom of the education pyramid are the teachers, modestly paid, overworked, doing their best for their young charges but groaning under the weight of soul-destroying paperwork. The middle of the pyramid is occupied by functionaries who fill their hours creating that paperwork, inventing endless tests and reports for humble teachers to implement. And at the top of the pyramid sit the directors-general and ministers whose appointed task it is to have grand visions of the future.”

Let me be clear: what Coetzee had just described was not the humdrum drone of the South African educational prosaic, but a Utopian ideal that every last citizen of this country would embrace, weeping with gratitude.Those “modestly paid, overworked” and “humble” teachers. There are thousands upon thousands of them. But there are also many – way, way too many – who arrive drunk, rape their students, and otherwise abuse their office. In return, they can expect the protection of a powerful teachers’ union that opposes changes to the system by reflex. Over-involved bureaucrats? We wish. Ministers with “grand visions of the future?” Is he kidding?

Well, maybe. At the end of the speech, I looked for a glint in his red-rimmed eyes, the curl of irony at the corner of his mouth. But one can spend a lifetime searching for glints and curls in the throwaway speeches of major literary figures. Indeed, many of the graduate students present had spent the past five years doing exactly that. As reward, they got an address either calibrated for Third World morons, or a postmodern joke with no discernible punch line.

Coetzee, though, has never done punch lines. They’re not his bag. In The Lives of Animals, when Elizabeth Costello makes a comparison between the Holocaust and the mass slaughter of animals for meat, an outraged Jewish professor boycotts a dinner in her honour. This is one of the great suites in postmodern literature: it presents and backs up a borderline indefensible position, and imagines and fictionalises an entirely plausible reaction. In other words, Elizabeth Costello’s words imagine their own critical reception – they are a game, albeit a serious one.

Was I the Jewish professor, playing a role assigned to me by postmodernism’s sharpest literary impresario? Or was I watching a dying intellect make the unforgiveable sin of talking down to a people easily bored by genteel musings on all things “edu-ma-cation,” as the other Homer calls it. Given all this, a Holocaust/meat speech would have seemed like light entertainment by comparison.

Unless, of course, we were played. In which case, we were easy marks. We came to hear a giant, flattering ourselves that we were worthy. Instead, I can’t help thinking that a nation that treats its children like rubbish got exactly what it deserved. DM

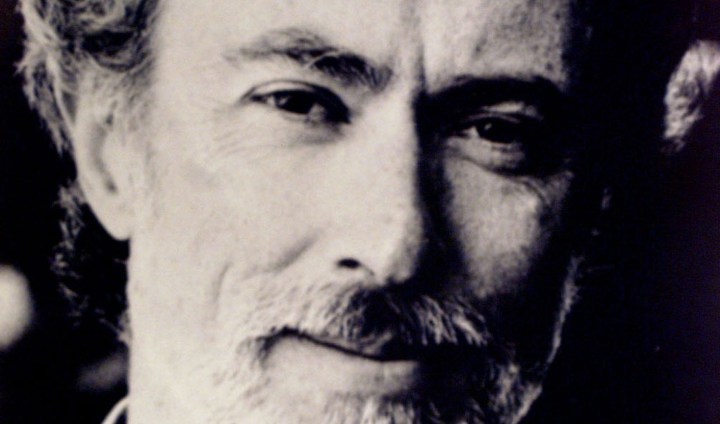

Photo: JM Coetzee (Reuters)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider