Maverick Life

Vertigo: The dizzying roller-coaster ride of an adult comic

On 3 December, Karen Berger announced her resignation as editor of Vertigo Comics, DC Comics’ ‘mature readers’ imprint from March 2013. Berger has spent 33 years at DC and has run Vertigo since its inception in 1993. PAUL BERKOWITZ looks back on the end of an era and forward to the likely future of Vertigo.

The early- to mid-90s was an interesting time for American comics. In the mainstream, monthly superhero world Superman was killed and Batman had his back broken. These events (some might say gimmicks) helped to blow up the market in a small orgy of speculative buying and trading as punters and patzers alike tried to pick and choose what might be “collectible”.

This graphic art bubble eventually did pop, and the bottom more or less fell out of the market. While the top titles (the Superman, Batman and X-men stables) could have shifted over a million copies a month during the height of the boom, by the turn of the century they would be lucky to sell a few hundred thousand.

Over the last five years few books have breached the 200,000 mark, and few have managed to sustain sales above 100,000 copies. The long-term trend is downward, for a number of reasons.

At the same time that the boys and girls in primary-coloured underpants were dominating the business headlines, a small independent company-within-a-company was being created that would redefine the American comics landscape for years. The bigwigs in DC’s New York offices thought that the time was ripe to publish comics for adults. They were right, and it had been a long time coming.

The Comics Code Authority (CCA) had cast a very long shadow of censorship over the comics industry in the 1950s and 1960s, all in the name of protecting the children. By the 1970s its influence was on the wane and by the 1980s it was a spent force.

It was during the 1980s that the first green shoots of resistance to the CCA could be seen by the major publishers. Marvel created the Epic Comics imprint in 1982 which went on to print a number of sci-fi and horror stories over its 14-year run – stories that the CCA in its joyless prime would never have sanctioned.

DC was slower to formalise its “comics for mature readers” division but it was doing plenty of its own rule-bending at the time, much of it edited by Berger. The 1982 relaunch of an old DC property, Swamp Thing, was meandering along in superhero form until Berger took over as editor. In February 1984 she handed the writing duties to a young English writer, one Alan Moore, and that was the beginning of the end for regular super-hero comics.

Before the year was up, Moore had covered incest, demonic possession and necrophilia in Swamp Thing and the CCA had rejected the book as a result. Swamp Thing (and DC by extension) in turn decided to reject the CCA. In future, the book carried the tag “Suggested for mature readers” and the CCA logo was conspicuous in its absence.

Swamp Thing was the first of a few DC titles that broke the rules and broke rank with the CCA. It was followed by Sandman; Hellblazer (a Swamp Thing spin-off); Shade, the Changing Man; Doom Patrol, and others. Some of these began as superhero stories, tethered to the DC universe and its pantheon, later to spin off into their own worlds. Others began life as thoroughbred adult horror stories. Almost all of these were edited by Berger.

Most of them were written by British writers (Neil Gaiman, Grant Morrison, Peter Milligan) who crossed the pond in the wake of Alan Moore; some had worked with Moore on the 2000AD comic in England. They were among the finest comic writers of their generation – some would say among the finest writers full stop.

By the early 1990s the number of DC books being recommended “for mature readers” had reached critical mass and DC decided to sort itself out, literally. Vertigo Comics was born in 1993, with Berger its midwife and den mother. The troublesome titles were removed from the DC mainstream and became Vertigo’s flagship titles.

For the rest of the decade the imprint would go from strength to strength, churning out a steady stream of highly readable ongoing titles and miniseries. The last of the rusty CCA foundations were swept away as Vertigo characters increasingly swore, had sex, did drugs and occasionally murdered other characters.

This isn’t to say that the “adult books” were just about the worst excesses of uncensored writing, or a backlash against the puritanical CCA. They were mainly about beautiful, complex writing which made American audiences realise what European readers had known for a while: comics were a viable medium for reaching adults. Maybe they could even be literature.

The finest example of this was the Sandman comic, another old DC property completely reinvented by a young, unknown writer. Neil Gaiman took a crime-fighter in a World War I gas-mask and turned him into one-seventh of a grand pantheon known as the Endless. The Sandman, aka Morpheus, aka Dream is the third-eldest sibling of a family of meta-gods (Destiny, Death, Destruction, Desire, Despair and Delirium are his brothers and sisters) who predate all the other gods and will be there to turn off the lights at the end of the universe.

Gaiman has the Sandman take over Hell when Lucifer abdicates his throne and befriend a man who can’t die (they renew their friendship every hundred years at the same pub in London), but it’s his chance encounter with a young William Shakespeare, and the subsequent deal struck, that caused all the controversy.

Issue 19 of Sandman, “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”, has Shakespeare and his company performing for Morpheus (and his guests, Titania and Auberon) as part of a deal between the two first mentioned in an earlier issue. “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” subsequently won the World Fantasy Award in the “Best Short Fiction” category under highly controversial circumstances.

Gaiman objected to being the sole recipient of the award, insisting that it be shared with Charles Vess, the artist. Many of the “real” writers (the ones with few, if any, pictures in their books) objected to the prize being awarded to a comic book. The rules for the awards were subsequently changed to exclude comics.

The horse had bolted by then. Adults were reading the books. Book writers were delving into comics. Collected editions of Vertigo stories were featuring on list of best-sellers, and some of the writers were now writing critically-acclaimed conventional books (Gaiman collaborated with Terry Pratchett on Good Omens, and enjoyed critical and commercial success with American Gods and Anansi Boys).

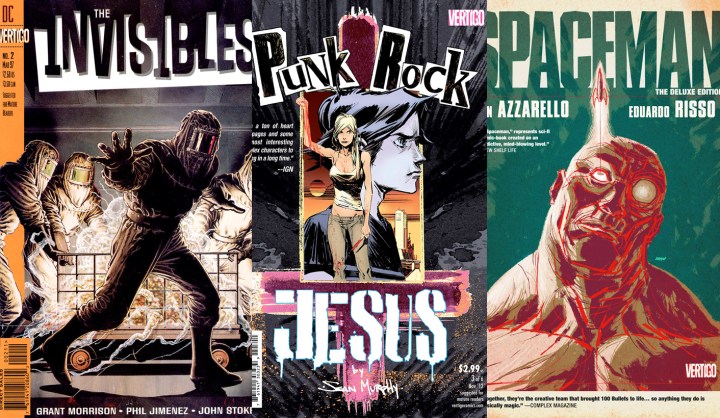

The critical acclaim continued after the initial titles had run their course, but the commercial success lagged a bit. The second and third generations of Vertigo’s ongoing titles contained many hits (Preacher, Transmetropolitan, Y: The Last Man) but more than their share of misses too. Sales numbers fell, and even the successful titles sold fewer copies than their predecessors.

In many ways Vertigo was just following the trend of the mainstream comics; maybe its initial commercial success was just the cresting of the wave created by mainstream comics’ big splash. There were periodic mutterings from industry analysts that Vertigo was different; its commercial pressures were lower and it could afford to sell fewer copies than its spandex sister titles; it had a larger market for its collected editions and the monthly singles could even be seen as loss-leaders; and so on.

The evidence does not paint a rosy picture. Vertigo currently has a couple of fairly solid properties (Fables and American Vampire) that sell above 10,000 copies a month, and even these sales are subject to slow sales declines. Many of the ongoing titles that were launched in the last two years have subsequently been cancelled, even as the sales threshold for cancellation has fallen.

In September 2011 DC embarked on a wholesale relaunch of its superhero titles. It included Swamp Thing in its relaunch – for the first time in 30 years the title would be set in the DC universe, not some Vertigo parallel. Animal Man, another title that was a Vertigo-via-DC book, was also returned to DC during the relaunch.

Around the time that Berger announced her resignation, it was confirmed that Vertigo would publish the final, 300th, issue of Hellblazer, its last remaining flagship book. The title is set to be relaunched by DC in the near future.

The wheel has turned full circle. Berger spearheaded the transformation of parts of the DC universe into the weird and wonderful world of Vertigo, and the current suits at DC have reversed the transformation, returning those parts to the original whole. Presumably DC reckons these properties have a better chance of commercial success in the mainstream, whether it’s merchandising, TV or movie spinoffs.

Vertigo is not dead, not yet at any rate. There is a line-up of new stories for at least 2013 that the company will release, and regular sales of its back catalogue should keep it in the black. The dream and the ethos of the 1990s Vertigo, of pushing boundaries and creator-owned properties, looks like it’s being rolled back before our eyes. The current crop of DC executives doesn’t appear to be supportive of Berger’s vision and direction.

We should keep an open mind and be supportive of Berger’s successor(s) but it feels like the end of an era. Let’s hope that bean-counting and the corporate hive-mind doesn’t do what censorship couldn’t – kill off the spirit that made comics cool for big kids. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider