South Africa

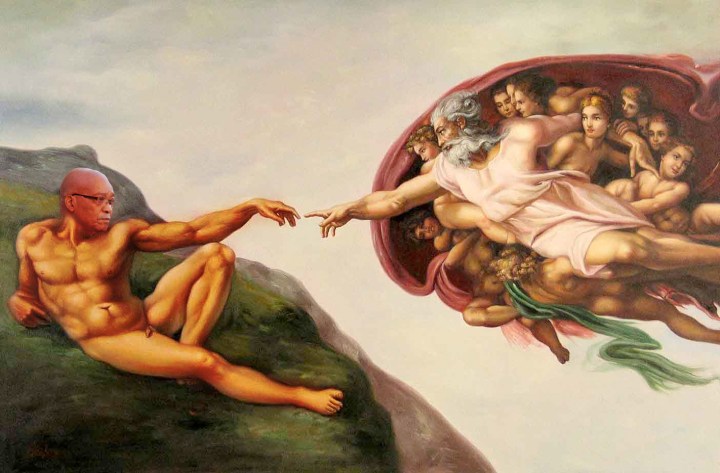

Analysis: We’re not in Eden anymore, South Africa

The deaths at Marikana have been called the end of innocence for post-Apartheid South Africa. Perhaps the spate of unexpected downgrades of the country’s sovereign debt and state-owned enterprises and the reverberations from the startling Economist cover story is South Africa’s expulsion from the delights of its geopolitical and economic Eden. By J. BROOKS SPECTOR.

Immediately after a pair of scathing articles on the state of South Africa were published in The Economist two warring tribes staked out the turf for their views of the South African experiment – and the world’s judgment of it.

Prophets of doom inside South Africa and beyond have taken a kind of smug satisfaction, a palpable “I told you so” schadenfreude, over the signs of South Africa’s imminent collapse, as adumbrated by The Economist. On the other side, the country’s ever-shrinking roster of cheerleaders – including some, but not even all, of the governing party’s political class – took umbrage over this international public insult unfairly sullying a nation that had inherited a savagely distorted economy, social structure and political system and that has since moved vigorously and aggressively to right these many wrongs.

In fact, both of these extremes have not quite hit the nail on the head. The Economist critique of South Africa’s circumstances was offered in sorrow and distress – the magazine clearly took little joy in this review of current circumstances. Its commentary was not an “Ah ha! Gotcha! You’ve been found out, the emperor has no clothes” exposé of a nation where everything has gone wrong and the precipice is close at hand. In fact, The Economist’s writers went to great pains to place the country’s current problems in their historical context and to identify the challenges from South Africa’s history that have produced its current circumstances.

At the same time, it noted the real advancement that has happened in housing, growing electrification, the expansion of basic education – and a general rise in income (much of it attributable to the extension of a social welfare systems that provides support grants to around a third of the country). And this real progress is acknowledged and applauded for what it is.

However, this country’s circumstances are now being measured against a continent whose larger circumstances and likely future is very different than was true a decade or so earlier. Back in 2000, The Economist had despaired of Africa as the hopeless continent.

At that time, in sharp contrast, South Africa was the one great shining beacon on the continent. It was energized by a new democratic tradition, abundant income from its extraordinary endowment of natural resources whose production and revenue had just entered the long cycle commodity boom. This almost guaranteed growing wealth to do ever more good.

But, in contrast, within the past year, The Economist has reversed the order – the rest of the continent, except perhaps for actual war zones like Mali, Somalia or the eastern Congo, is a region of “go-go” possibilities. Even Nigeria, sometimes seemingly perched on the lip of a social and political volcano, is now viewed as a likely candidate to surpass South Africa’s GDP in a few years. South Africa is the place where the future has gone sour.

Government and other cheerleaders have been quick to reply with anger or in pain that The Economist has got it all wrong. South Africa has problems, yes, but there is a will to deal with them, resources to address them and the international respect (its BRICS membership, the UN Security Council role, a South African as head of the AU Commission) to bolster just such efforts. The country’s economy is basically sound, there is an appetite for new infrastructure and plans to put it in place, and its sovereign debt has just been included into a world bond index as a mark of respect for what has been achieved here. And besides, this South Afro-pessimism is really – at its heart – envy for what has already been achieved by an African nation.

But some things can’t be ignored or wished away. And that is the crux of things. The country continues to bleed away manufacturing, mining and agricultural jobs as its economy shifts increasingly into a service economy, but its education system has not kept up in quality or quantity to respond to the new challenges. Absent such an effort, and the foundation for real economic growth is forever weakened. And in fact, the critics now say, South Africa is slipping behind, despite a major contribution from the national budget to education. It is slipping in comparison to other African nations, let alone to putative competitors in South Asia, Southeast Asia or Latin America.

As South Africa enters into its year-end examination period, some cruel facts bear noting. Out of a student cohort of a little over 1-million who entered the 10th grade, fewer than 400,000 will have passed the school-leaving exam two years later, with just a 30-40% aggregate level pass. Moreover, fewer than 150,000 will have received a minimum university acceptance-level passing grade. And of that now-shrunken subtotal, around only 50,000 or so will have achieved a 50% passing level in mathematics, and less than 10,000 will have achieved an 80% level in that subject. But this is the very subject that is the core of capability in so many of the fields that make up the new economy. This level of achievement and accomplishment is not the mark of a society prepared for the challenges of a 21st century economy.

Even putting aside garden-variety issues like service delivery protests, increasingly obvious systemic corruption and glaring inefficiencies in government, the rentier gatekeeping economically, a growing opting out of the contemporary political landscape by disaffected citizens, rising and increasingly violent labour unrest and a lack of sustained investment in infrastructure during the past decade that leaves a huge catch-up gap, the problem is not just a lack of social, educational and economic preparedness for the future for many of South Africa’s least well-equipped population.

The looming problem now is that the rest of world is in a fierce, unrelenting competition for whatever investment capital is available. While places like China, India or Brazil continue to suck in such investment capital, South Africa has now begun to stagnate on this front – or worse.

More than a decade ago, in his book The Lexus and the Olive Tree, New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman observed the new global liquidity of investment capital in combination with growing electronic capabilities to move money around almost instantaneously and coined the phrase “the electronic herd”. This electronic herd acts like springbok or a school of herring – the slightest threatening movement, shadow or noise is enough to send the herd – whether animal, fish or investment banker – slewing off in an entirely different direction at a moment’s notice. Sometimes the trigger for the flight is a false alarm, but sometimes not. But the intense mobility of capital mimics the behaviour of all those frightened fish that don’t wish to get eaten by other fish.

As if to prove this point, this week’s news contains the startling information that FDI – foreign direct investment – in South Africa has dropped an astonishing 43% year on year, and much of the drop seems to be connected to signals South Africa is unfriendly towards FDI. This unfriendliness is a combination of the tussle between different government departments over who actually owns national investment policy; a sense that the country has truly restrictive labour mobility; a fight over the conditions by which big box retailer Wal-Mart could enter this country’s retail and wholesale markets; as well as the downward impact on potential investors from continuing turmoil and worse in the mining sector.

Now that the long cycle commodity boom seems to be over, even the mining sector will have to fight much harder with increasingly less success to gain any traction with that increasingly skittish electronic herd of potential investors. This puts a real crimp on future growth in production or revenues.

And so, having been expelled from a blissful paradise of the world’s admiration and love, perhaps South Africa is now entering a time when observers will look carefully at virtually any handwriting that may appear on the wall in an effort to help foretell the future. The problem is, it seems less and less likely the words will spell out, “This way to the promised land” and more likely to say, “Mene, mene, tekel, upsharim,” those mysterious words Daniel was summoned to interpret for Babylonian king Belshazzar.

If readers can recall their Scripture, after he entered the king’s chamber, Daniel had told Belshazzar the words meant he had been weighed, measured and found wanting; that his kingdom would be divided and given over to the Medes and Persians. For South Africa, the question for the current crop of political leaders who stay up late contemplating the fate of the country’s undereducated, unemployed, disaffected and unemployable almost certainly will be: Exactly who are their Medes and Persians, riding down from the distant hills – and what will they want when they finally arrive. DM

Read more:

- “Sad South Africa – Cry, the beloved country,” on The Economist

- “Over the rainbow,” on The Economist

- “Africa rising,” on The Economist

- “Africa at work: Job creation and inclusive growth,” a McKinsey job creation strategy for Africa

- “The Economist gets it wrong – again,” blog post by economic journalist Reg Rumney

- “Hopeless Africa,” on The Economist

Become an Insider

Become an Insider