South Africa

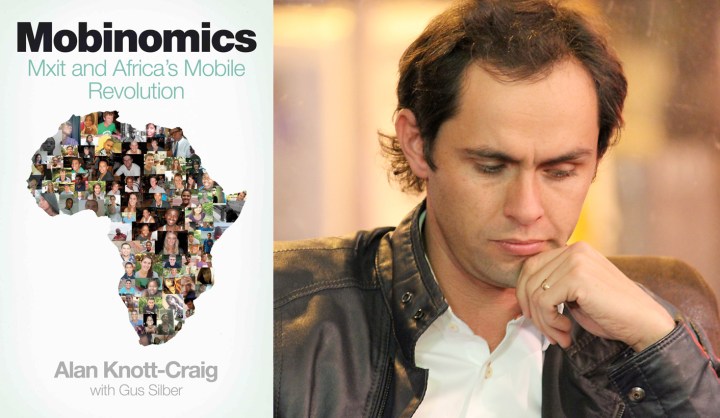

Mobinomics: A story about the social network

It’s the stuff of parental headaches and teenage dreams. We’re not talking about Facebook or Twitter – we’re talking about MXit, the cellphone-based social network with over 50 million users. If you think of your cellphone as nothing more than a wireless communication device, re-consider: Alan Knott-Craig and Gus Silber’s Mobinomics argues that it’s part of what might just be an Africa-wide revolution. By REBECCA DAVIS.

Cellphone ownership in South Africa is no longer the province of the rich: mobile penetration now exceeds 90%, according to the authors (with some sources claiming over 95% or even 101%, depending on the age group). That’s a massive market, and it’s not just cellular networks that want a piece of it. The most-hyped cellphone-based enterprise on the continent is MXit, which writer Gus Silber calls “one of the three great South African innovations, next to the heart transplant and the Kreepy Krauly”. Of course, it’s in his interest to claim that, since he’s just co-authored a book on the subject with MXit CEO Alan Knott-Craig. But the story of MXit’s extraordinary growth is indeed an inspiring one, and Mobinomics turns out to be a highly readable account of the company’s success in harnessing the potential of the cellphone-using market. [Disclosure: Alan Knott-Craig was Daily Maverick’s first investor. World of Avatar holds a stake in Daily Maverick.]

“I met Alan in 2010 to chat about the possibility of a book about “Mobinomics”, the economy of mobile in Africa. Which means everything from the use of mobiles in commerce and banking, to social media, to social upliftment,” Silber explains. “As part of this process, Alan showed me a presentation on his laptop about MXit, which he used as an example of the spread of mobile in South Africa, and it was quite eye-opening for me to see just how big the network’s reach is, and how there is a lot more to it than chatting.”

At that stage, MXit was owned by founder Herman Heunis, with Naspers having a one-third stake. Four years previously, in 2006, Knott-Craig (who was at the time running a wireless service provider called iBurst) had tried to buy a stake in the business from Heunis, but couldn’t afford the R35-million asking price. By that stage, the one year-old company had only 360,000 users, but its potential was clear. Looking back, Mobinomics records, “what [Heunis] was asking was a pittance”. Nonetheless, it was out of Knott-Craig’s reach, and he had to walk away.

Then, in 2011, Silber ran into Knott-Craig in Johannesburg’s Melrose Arch. “He said he had to dash because he was going to buy MXit,” Silber says. “I thought he was joking, but he was serious. He did the deal.”

Silber makes it sound easy, but Mobinomics reveals that there was a fair amount of blood, sweat and tears that went into that deal. Heunis was keen to sell, having fallen out with Naspers, and had indicated that he would accept a price of R669 million. “My gut said anything less than a billion was a steal,” Knott-Craig writes. But, for the second time, Knott-Craig couldn’t raise the cash.

He was crushed, thinking he’d lost the deal, but his attorney suggested that Heunis might be gatvol enough to accept a cash offer. It turned out this hunch was correct. Knott-Craig was able to raise enough to make a cash offer of R330 million. On 16th September 2011, Knott-Craig’s ‘World of Avatar’ company became the new owner of MXit.

Mobinomics has a dual focus: it tells both the story of MXit, and how that encapsulates the meaning of “mobinomics”, and the personal story of Knott-Craig. This latter aspect is refreshingly candid. We learn, for instance, about the young Knott-Craig’s high-school suspension for drinking; his almost-firing from Deloitte, while doing articles, for bunking and being on a porn distribution list; and the damage his success with iBurst did to his relationship with his wife and family. The openness in this respect is a canny move, because it leads one to root for MXit’s success in a way you might not think likely when appraising the massive growth of a tech company.

To write the book, Silber spent long hours in conversation with Knott-Craig and MXit users and developers. He notes that “Alan, by the way, is a very nice writer, and he wrote several pieces that found their way into the book in one form or another”. (Knott-Craig authored a previous book, 2008’s Don’t Panic, which grew out of a pep-up email he sent to his staff that went viral.) Mobinomics has an interesting story to tell, but it owes much of its readability to Silber’s easy style and the gentle, humorous touches familiar to his many Twitter followers: he notes that one of the first MXit programmes was “an early variant of the principle of social networking, or as it was then known, ‘meeting people’.”

If you don’t fall into MXit’s core demographic – 12- to 25-year-olds – you may be surprised to learn just how many areas of users’ lives the network now stakes a claim to. Its main business is gaming and chat – a 2011 Unicef study found that 30% of school-going respondents spent their time at home chatting on MXit, as opposed to the 16% who watched TV and the 13,5% who did homework – but there is now much more to it than that. Other applications range from the therapeutic – RLabs, a Cape Flats-grown counselling service, where you can receive a text-based counselling service for around 88c – to the academic: Dr Math, where university students give free Maths advice to 30,000 MXit users after school hours.

They are also working on further development of the MXit wallet, a “digital trade and payment system powered by your cellphone”, which is touted as a proposed solution to the fact that not everyone has access to a debit card. MXit employees are given a lunch allowance via MXit wallet of R43 a day as a way of testing the system. When they came to analyse the results, they found that most of the money was being spent at Kauai, which was interesting because the health-food chain was located substantially further than other restaurants close to the office. Then they hit on the reason for its popularity: because it was a little cheaper than the alternatives. “There is something about mobile technology that encourages you to think small, to rationalise and ration your spending,” they suggest. If true, it’s an intriguing notion.

As a working environment, MXit comes across as an office in the Google vein of things – employees can wear what they like, top-of-the-range coffee is available with a full-time barista, and there’s an emphasis on corporate trust: everyone in the office can sign cheques for up to R10,000 without endorsement. Knott-Craig made the decision to strip away a Human Resources department and a Business Intelligence unit as part of his belief that “scarcity of resources can often be the mother of invention. Great things can happen when people are given the freedom to figure things out for themselves.”

We also learn, however, that MXit employees receive no benefits – no medical aid and no pension. “People must take responsibility for their own lives, and the nuances of their own finances,” Knott-Craig believes. “You actually disempower people when you take that responsibility away.” That’s a fairly contentious notion, and also one at odds with his professed political beliefs – he is not a libertarian, we are told, and believes in the role of government.

The social network of MXit itself is built around the metaphor of a country: “We’ve got infrastructure, we’ve got systems, we’ve got networks, we’ve got markets, we’ve got an economy. We’ve even got a government. And the job of a government is to serve and protect the people of the country, and make it as easy as possible for them to make a living”. This trope of MXit-as-country recurs throughout the book – if MXit were a country, by the way, it would be the fifth most populous country in Africa.

Yet sometimes it seems that what Mobinomics suggests is that MXit is not merely a country, but a Utopia. Of MXit’s famously cheap messaging rates (2c per message) compared to standard cellphone SMS rates, they write that from the outset, “it became a political movement, rallying people to the cause with a principle of economic redistribution that came straight from the handbook of a legendary socialist hero, Robin Hood”. This seems hyperbolic, cheap as MXit is.

Some of the most interesting parts of Mobinomics are devoted to exploring the culture of the network itself, which can seem baffling to outsiders. MXit users – MXiteers – send more than 23 billion messages a month, mostly using a language Silber terms ‘Mxlish’ – “a mixture of SMS-speak, SA slang and spelling mistakes”. This code can be so impenetrable to read that MXit has an in-house software system called the MXit Understander, designed to help ‘Dr Math’ volunteers to interpret questions from pupils which often come in forms like: “i need help wit my mathz i can subtract fwm 180 dgrez 4 da anonymas anglz”. It’s enough to give English teachers a full-blown headache.

In recent years MXit has occasionally made headlines for reasons less palatable than those highlighted by the book, such as the 2011 story about the Hawks arresting a former policeman who headed a child porn ring allegedly spreading content via MXit. There is, however, a chapter presumably designed to pre-empt this particular concern, which details the extensive monitoring of the network to ban users disseminating inappropriate content.

One criticism levelled at the network which Mobinomics can’t really refute, however, is the astonishing amount of time school pupils spend using it: Silber encountered one high-school student who once spent nine hours straight chatting on the network. This aspect has been the subject of much concern from parents and educators, with MXit even being blamed (according to News24) for poor exam results in the Eastern Cape in 2006. Mobinomics is at pains to underscore the more positive sides of MXit use, however, such as the educational applications and, indeed, its potential for creating and solidifying relationships. (There’s even a MXit marriage story.)

MXit is not raking in huge bucks just yet – the book’s concluding chapter notes that the company burns through R4 million a month. But at its current rate of expansion, the future certainly looks bright. There’s a hint at the book’s ending that MXit is looking into evolving into a telco of its own, tired of seeing the airtime spend of its users go into the pockets of the cellular networks. That’s a big plan, but what Mobinomics makes clear is that this has never been a company, or a CEO, scared of dreaming big. DM

Disclaimer: Alan Knott-Craig Jr is a shareholder in The Daily Maverick, which Mobinomics kindly terms “a journal of news and commentary that is helping to shape the way we see our noisy, disruptive democracy”.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider