World

Rodney King is dead: a face of American inequality is gone

One of the strangest chapters in American history is now closed. Rodney King, the petty criminal whose vicious beating sparked the 1992 Los Angeles riots, is dead at 47. By RICHARD POPLAK.

The damndest thing about Rodney King, the ne’er-do-well Los Angelino who drove a Hyundai into history, is that he was born the year of the Watts riots. A sweltering August day in 1965: a young black man named Marquette Frye is pulled over by the police, who believe that he is driving under the influence. Half an hour later, the inner city ‘hood has crowded around the impounded car, yelling at the hated L.A.P.D. officers. A week later, 34 people were dead, over 3,400 arrested and inner city Los Angeles resembled a Viet Cong village after a bombing sortie.

Those riots would come to be a prelude of sorts for those that followed almost three decades later. The 1992 Rodney King riots, so named for the man who ostensibly kicked them off, proved that little in America had changed since the Civil Rights era. It was still business as usual to treat blacks as second-class citizens, and to visit brutality upon them should the occasion arise.

The occasion did indeed arise on March 3, 1991, when a Hyundai bearing an inebriated 25-year-old black man sped past police at about 160km/h. Rodney King was on parole for a robbery conviction. He’d struggled with drugs and alcohol his whole life and had watched his father, Ronald, do the same. Had that night unfolded like so many other nights in King’s short, unhappy life, he would have been busted, thrown back in jail, and the cycle would have continued. Much the same as it had for his father, who died unredeemed at the age of 42.

But that night was destined to be different, and King was about to join Malcolm X, Rosa Parks and other names etched on the edifice of the American Civil Rights pantheon. When the cops finally pulled him over, King made a run for it. He was taken down, smashed with batons, Tasered – thoroughly beaten by four police officers, while several others looked on like it was another day at the office. (Which, according to most black people in L.A., it was.) The beating was videotaped by a man named George Holliday—America’s second most memorable instance of citizen journalism, following the Zaprunder film of 1963 JFK assassination – and the tape went viral in the old school sense of the term: every TV news station in the world picked it up.

The images were ghastly. Holliday’s tape landed, like Zapruder, as an instance of American brutality unfiltered and un-stage managed. As King rose to defend himself, Taser wires hanging off him, there was nothing in the Hollywood lexico – nothing in the hundreds of thousands of images of violence filmed over the course of the 20th century – that spoke so eloquently of America’s essential indignities. All of McLuhan’s glib one-liners fell away: the message was clear. America had an under-class, represented by a lone black man preyed upon by a ring of armed whites.

And so a petty criminal with a line of drug and alcohol abuse was flung into the maelstrom of American history. Broken ankle, broken facial bones, bruised up and battered, King sued, the Los Angeles police force tried to make the allegations go away. By the time the four officers were acquitted by a jury with no black members one year later, Los Angeles was a powder keg. And it blew sky high.

“Can’t we all just get along?” begged King on television as he watched L.A. burn. Fifty-three lives, 3,000 businesses, one billion dollars – all went up in smoke. King tried to escape the insanity by driving away in disguise, but he couldn’t do it. “It got so scary,” King remembered. “It felt almost like we were headed to Armageddon. Everybody had their own reasons. It wasn’t just police brutality. It was the way people were being treated over the years. People were [telling me to] say nothing, or go out there and say, ‘Burn it up,’ but I was, like, no, that’s not how I was raised. It was a bad time, a combination of everything – race relations, police brutality, poverty.”

L.A. was eventually quieted; King was paid out over three million dollars in damages (he bought his mother a house; he bought himself a house; he started a hip-hop label that failed). His life fell back into its inevitable pattern: drink, drugs, arrests for domestic assault. Because he was a catalyst for American renewal, he lived a quintessentially American life: stints on Celebrity Rehab and Sober House; self-improvement projects; a memoir released in April of this year, called The Riot Within. He was not Rosa Parks, but it’s impossible to imagine a black American president without King’s beating and the subsequent brouhaha.

Despite his peccadilloes, King never seemed like a bad guy. He was just baffled. “I can’t move on if I’m feeling all hard and hateful inside,” he once said. “It just takes up so much energy. It’s hard to walk around all bitter all the time. I don’t see how you can grow as a world without being able to get along with people. So many people is hating out there and it’s not making a difference.”

On Sunday, Rodney King was found by his fiancé at the bottom of a pool in his home in Rialto. No foul play is expected. In all things, King was a man of destiny. He was destined to change the course of American history; he was destined to live the desultory life of the second-generation addict. In both of those widely divergent paths, he was nothing less than your average guy, beholden to his own needs, but also painfully aware of the wider world around him, in all of its manifest insanity. DM

Read more:

Rodney King seen as neither hero nor villain but as catalyst for change in policing across US in Washington Post;

Rodney King dies at 47; victim of brutal beating became reluctant symbol of race relations in LA Times.

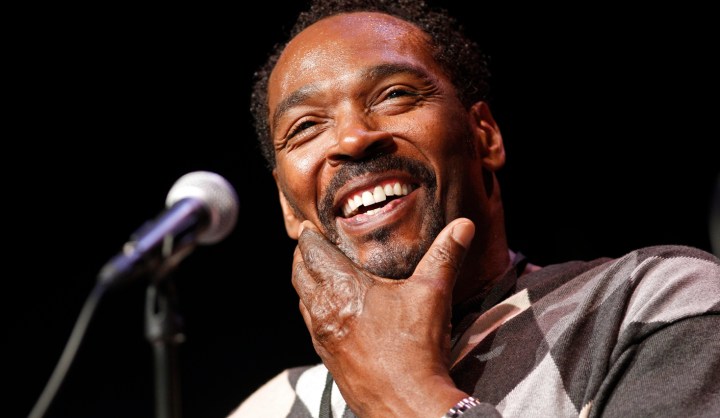

Photo: Rodney King smiles during a discussion for his memoir entitled “The Riot Within: My Journey from Rebellion to Redemption” at the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books on the campus of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles April 21, 2012. April 29 marks the 20th anniversary of the L.A. riots, which started when LAPD officers were acquitted after being accused of beating Rodney King during his March 3, 1991 arrest. REUTERS/Danny Moloshok

Become an Insider

Become an Insider