Newsdeck

Tiananmen villain seeks to clear his name

Former Beijing mayor Chen Xitong has long been seen as instrumental in persuading China's then-paramount leader Deng Xiaoping to launch the 1989 assault on protesters that gained notoriety as the Tiananmen massacre. Aged 81 and facing death from cancer, he now claims he was a scapegoat and that, sooner or later, the truth of those June events will fully emerge. By Kent Ewing

The man long portrayed as one of the arch villains in the Chinese government’s bloody crackdown on pro-democracy demonstrators in Tiananmen Square (23 years ago yesterday) now claims to be its chief scapegoat.

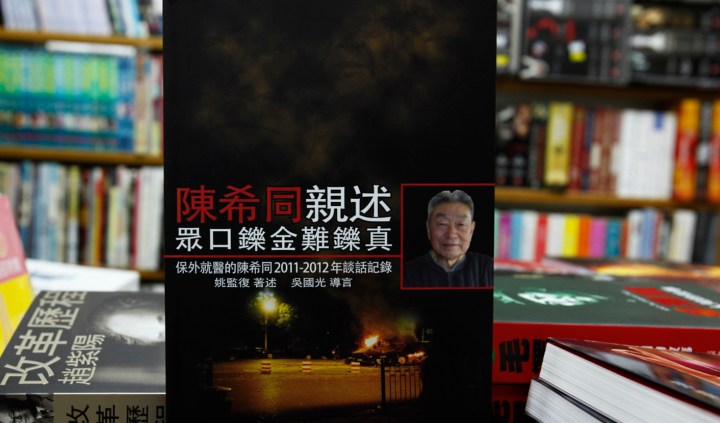

In a book released last week in Hong Kong, former Beijing mayor Chen Xitong – 81 this year and in the late stages of colon cancer – makes an effort to clear his name and put himself on the right side of Tiananmen history, along with famous reformers like Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang, who were both purged as Communist Party leaders for their liberal ideas. If true, the book, Conversations with Chen Xitong, compiled by scholar Yao Jianfu, dramatically changes perceptions of a key figure in this dark chapter in modern Chinese history.

It has long been believed that Chen was a hardliner who was instrumental in persuading then-paramount leader Deng Xiaoping to mount a military assault on student-led protestors who, demanding democratic reforms, had occupied the square for nearly two months in the spring of 1989.

By some accounts, Chen even exaggerated the security threat represented by the students in his efforts to convince Deng to launch the brutal operation, which started on the night of June 3 and spilled over into the next day, restoring order but leaving hundreds, if not thousands, dead. It also killed any further debate about political reform in China.

The Tiananmen protests were initially sparked by the death of Hu, a former general secretary of the party, who had become a rallying symbol for reformers. Zhao, Hu’s successor as general secretary, was removed for opposing the crackdown and placed under house arrest until his death, at age 85, in January of 2005.

Zhao’s memoirs, Journey of Reforms, secretly recorded while he was under house arrest in Beijing, were also published in Hong Kong, by New Century Press, on May 29, 2009, just days ahead of the 20th anniversary of the crackdown.

But Zhao’s memoirs – full of criticism for Beijing’s authoritarian rule and praise for Western-style democracy – are consistent with the accepted Tiananmen narrative that ties his fall to his support of the ideals promoted by the students during those fateful seven weeks of hope and despair in 1989.

Yao’s book of conversations with Chen, also published by New Century, defies that narrative, however. In a series of eight interviews conducted between January 2011 and April 2012, Chen depicts himself as a closet liberal who had nothing to do with the decision to unleash the PLA on the demonstrators, calling the violent suppression of the Tiananmen protests “a regrettable tragedy that could have been avoided”.

While he wanted to bring an end to “the turbulence” of the demonstrations, Chen tells Yao, he did not advocate bloodshed.

“Nobody should have died if it was handled properly,” Chen is quoted as saying. “Several hundred people died that day. As the mayor, I felt sorry. I hoped we would solve the case peacefully. Many things are still not clear, but I believe one day the truth will come out.”

But can Chen’s newly minted description of his role in the carnage that occurred that day be trusted?

After all, this is the same man who, on June 30, 1989, was chosen by the Chinese leadership to deliver the official report on the crackdown to the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress. At that time, Chen called the pro-democracy demonstrations “a counter-revolutionary riot” that justified the use of force – a stance that the Chinese government has maintained to this day.

As Chen relates the story to Yao, however, although he dutifully read the report, he had no hand in writing it and did not endorse its findings.

“I faithfully read the article they [Deng and other leaders] prepared for me, even down to every last piece of punctuation,” he said.

At least in part due to his loyalty during the Tiananmen debacle, Chen was promoted to Beijing party secretary and appointed to the ruling Politburo: a loyal bureaucratic soldier was receiving his just rewards. Clearly, Chen’s star was on the rise; if he had secret liberal leanings, he kept them well hidden.

Soon, however, Chen’s political career would come crashing down in circumstances that he now compares to the recent fall of Chongqing party boss Bo Xilai, who stands accused of “serious disciplinary violations” that are likely to turn into charges of corruption; meanwhile, Bo’s wife, Gu Kailai, has been arrested for the murder of British businessman Neil Heywood.

Like Bo earlier this year and former Shanghai party chief Chen Liangyu, who was deposed in 2006, the ambitious Chen got caught up in a power struggle with the ruling elite and was strung up on corruption charges.

As the leader of the so-called “Beijing clique”, Chen was seen as a rival to then President Jiang Zemin, head of the “Shanghai clique.” Rumours have long circulated that Jiang suspected Chen of undermining him in a damning letter written to Deng and that Bo Yibo – the late father of Bo Xilai and one of the party’s “eight immortals” – had informed Jiang about the contents of that letter.

Whatever the case, Chen was arrested for corruption in 1995. Three years later, he was convicted of accepting 550,000 yuan (US$86,000) in bribes and dipping into public coffers to build luxury homes for himself. He was sentenced to 16 years in Qingcheng Prison – ironically, the same damp, dark, secretive place where many of the Tiananmen student leaders were jailed.

He was released in 2006 on medical parole and appears to be a dying man worrying over his legacy. He tells his biographer that he never tried to bring down Jiang and suggests that the corruption charges against him were all a fabricated product of Jiang’s paranoia. “I have never treated Jiang as an enemy,” Chen says. “I resolutely supported Jiang and respected him.”

Chen calls his corruption conviction “the biggest injustice since the Cultural Revolution” and denies all charges made against him.

Indeed, it seems the dark cloud of corruption that hangs over his record troubles him more than what he characterizes as his passive but reluctant role in the decision to send tanks rolling into Tiananmen Square 23 years ago.

While he was in prison, Chen says, he refused the monthly allowance of 3,500 yuan (US$550) to which he was entitled as a way of demonstrating that he did not accept the court ruling against him, adding that his conversations with Yao were motivated by the repeated rebuffs he received when he appealed to authorities for a review of his case.

“I have no choice but to speak out,” he said. “This is to defend the truth, and it is in line with our party’s principle. If the People’s Supreme Court cannot reverse my case, their claim of judicial independence is a lie.”

Ultimately, history will be the judge in Chen’s case. In the meantime, another June 4th anniversary has come and gone. Once again, with Beijing under a security lockdown, tens of thousands of people attended the annual candlelight tribute to the Tiananmen victims in Hong Kong’s Victoria Park, and other poignant remembrances were held around the world calling on the Chinese government to reverse its verdict on the 1989 pro-democracy movement as a “counter-revolutionary rebellion”.

As of today, that verdict remains unchanged. DM

Credit: This edited article is used courtesy of Asia Times Online (http://www.atimes.com/), who retain copyright.

Photo: A copy of the book “Conversations With Chen Xitong”, published by Hong Kong’s New Century Media, is shown to the media inside a bookstore in Hong Kong May 31, 2012, one day before its official launch in the territory. Chen, a former Communist Party chief of Beijing who was at the heart of one of China’s biggest political scandals before this year’s upheaval over Bo Xilai has challenged charges that brought him prison and disgrace in a book likely to stir controversy. Chen was dismissed as Communist Party secretary of Beijing in 1995 and later jailed on corruption charges, which many observers at the time saw as resulting from a power struggle pitting him against then President Jiang Zemin. The subtitle of the book reads, “public clamour can melt metal, but it’s difficult to melt truth — conversations in 2011 and 2012 with Chen Xitong who is on medical parole.” REUTERS/Bobby Yip

Become an Insider

Become an Insider