In September last year, a few months before he died, Christopher Hitchens laid out in characteristically compelling detail his arguments against the death penalty. Entitled “Staking a Life,” the piece, published in Lapham’s Quarterly (the journal of former Harper’s Magazine editor Lewis Lapham), opened with the reasons that Britain and France had abolished capital punishment.

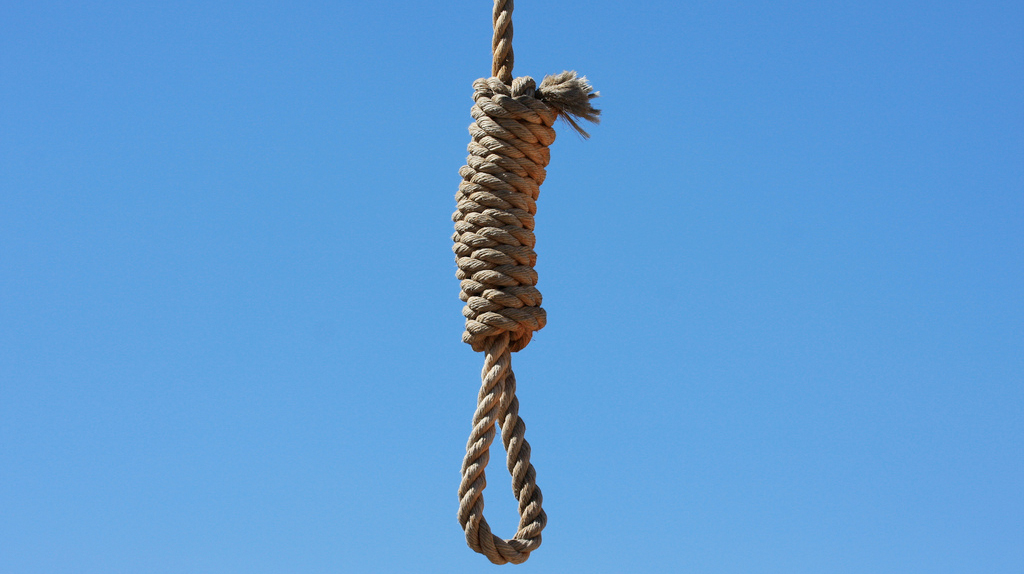

In the former, Hitchens observed, where the final hanging occurred in 1964, the ultimate sentence was done away with due to a growing discomfort about the possible execution of innocents. In the latter, he continued, the early 1980s saw the official abolishment of the peine de mort, mainly because Francois Mitterand’s administration wanted to get rid of the totalitarian symbolism associated with the scaffold (the last time a Frenchman was sent to the guillotine was in 1977).

Hitchens then pointed out that no country has since been allowed to join the European Union without first abolishing the death penalty, that the United Nations condemns it, and that the Vatican has come very close to forbidding it outright. The next point the writer made, of course, was that this left only the United States, alone among the group of nations commonly referred to as the West, which has not only kept the form of punishment but actually expanded its use.

“To be in the company of Iran and China and Sudan as a leader among states conducting execution,” he wrote, “– and to have pioneered the medicalised or euthanised form of it that is now added to the panoply of gassing, hanging, shooting, and electrocution and known as ‘lethal injection’ – is to have invited the question why. Why is the United States so wedded to the infliction of the death penalty?”

But before venturing into Hitchens’ answers to himself, and his concomitant reasoning for standing firmly against all forms of state-sanctioned execution, it seems we now have to ask ourselves this: what would the deceased and sorely missed author have made of the fact that the Columbia Human Rights Law Review is dedicating its entire spring edition to the execution, in 1989, of a man who was innocent of the crime?

We can be fairly certain that Hitchens would have been all over this new development, mainly because the circumstances of the case closely mirror his own hypothetical scenarios in the Quarterly article, but also because the story is so central to America’s moral conception of itself that the Columbia Review has doubled its normal size to 436 pages.

The august review has also put together a website enabling access for less legal-minded readers. Amongst the evidence available for the general public to explore are crime scene photos, law enforcement and court records, newspaper and TV coverage, police audiotape of the manhunt ending in the executed man’s arrest, and an interactive map.

Based, according to the website, on one of the most thorough investigations of a criminal case in United States history, the book-length monograph, written by Columbia Law School Professor James Liebman and a team of students, appears to establish beyond doubt that Carlos DeLuna was wrongfully put to death. It seems the real killer of Wanda Lopez – she had been stabbed in the left breast with a lock-blade knife – was an almost identical lookalike of DeLuna’s, a violent criminal by the name of Carlos Hernandez.

Videos on the website explain that from the moment of DeLuna’s arrest to the moment of his execution six years later, he not only maintained his innocence but said repeatedly that he knew who the real killer was. Further, although the prosecutor said at the time of the case that Hernandez was a “phantom,” evidence uncovered years later shows not only that he existed, but that he was well known to police.

A report that ran in Salon.com on Tuesday, 15 May, adds: “As DeLuna languished on death row, Hernandez managed to get arrested nine times, once for killing a woman and another time for stabbing a Hispanic woman nearly to death. Again, the police and District Attorney failed to inform DeLuna’s lawyers and the judges overseeing his appeals. Meanwhile, the prosecution continued to argue that Carlos Hernandez did not exist outside of DeLuna’s mind.”

The Guardian newspaper goes on to note that four years after DeLuna’s death by lethal injection, Liebman, who was conducting an extensive study into the problems associated with capital punishment, hired a private investigator to spend a single day tracking down Hernandez. By the end of that day the investigator had found him, and had come across details that unlocked his criminal past.

Liebman and his team of students then established that Hernandez, who was arrested a total of 39 times but almost never put in prison, was a police informant – a fact that may have explained why the Corpus Christi cops were loath to acknowledge DeLuna’s version. Not only that, they also discovered that Hernandez had actually boasted about being responsible for the murder of Wanda Lopez.

“Hernandez himself frequently told people that he was a knife murderer,” the Guardian reported earlier this week. “He made numerous confessions to having killed Wanda Lopez, the crime for which DeLuna was executed, joking with friends and relatives that his ‘tocayo’ had taken the fall. His admissions were so widely broadcast that even Corpus Christi police detectives came to hear about them… Yet this was the same Carlos Hernandez who prosecutors told the jury did not exist. This was the figment of Carlos DeLuna's imagination.”

Following this, the rest of the evidence collected by the Columbia team almost pales by comparison. There was the fact that DeLuna was put on death row largely due to the eyewitness testimony of one man, who 20 years later admitted he couldn’t have been entirely sure because he always had trouble “telling one Hispanic person apart from another”. There was also the fact that forensic procedures at the crime scene were practically non-existent – no blood samples were collected, no usable fingerprints were taken, and “there was no scraping of the victim's fingernails for traces of the attacker's skin”.

Still, coming at a time when pressure for abolition of the death penalty in the United States is gaining steam, the exhaustiveness of the full 436-page report could turn out to be a decisive factor. In April, Connecticut became the fifth state in as many years to do away with capital punishment, and it is Liebman’s hope that the remaining states will be swayed by the “ordinariness” of this miscarriage of justice.

Which brings us back to Hitchens and the central question he asked in that article last September: why is the United States alone among Western nations in keeping the death penalty as an option? Initially, the answers that appeared to make the most sense to the writer were twofold. First, he observed an old link between executions and racism, particularly as regards the history of slavery in the south. Second, he noted the relatively short lapse of time between the contemporary United States and the wild days of frontier justice.

As for the racism answer, the DeLuna case appears to speak for itself, especially since the single eyewitness admitted decades later that he had trouble telling Hispanic people apart. Yet on reflection, for Hitchens this wouldn’t have explained why “the penalty has lately been restored in New York and California, and why a Federal execution ‘facility’ has been built in Terre Haute, Indiana, birthplace of Eugene Debs (and used as a launching pad from which to kick the ultra-white Timothy McVeigh off the planet)”.

Likewise, the temporal proximity to the untamed rough justice of the frontier also began to present problems for The Hitch, mainly because “Europe in the last few decades saw a very great deal more violence and chaos on its own soil than any American has ever had to witness on home turf…”

So what, then, was his answer?

Unsurprisingly for someone who wrote a book called God is Not Great, and who refused to acknowledge the possibility of a deity even while he was dying painfully of throat cancer, his final answer was this: “The point of the penalty was that it was death. It expressed righteous revulsion and symbolized rectitude and retribution. Voila tout! The reason why the United States is alone among comparable countries in its commitment to doing this is that it is the most religious of those countries. (Take away only China, which is run by a very nervous oligarchy, and the remaining death-penalty states in the world will generally be noticeable as theocratic ones.)”

It is an undeniably persuasive assessment, one that would appear to cast real doubt on Liebman’s ability to force the abolition of the death penalty based on the circumstances of the DeLuna case. Unlike much of Europe and even South Africa, where the death penalty was abolished in 1995 – due to the enshrinement of the “right to life”, the eleven judges at the Constitutional Court voted unanimously – the United States remains a mostly “godfearing” country.

Which is arguably the chief reason that all its talk of liberty and freedom and human rights is essentially empty. As Hitchens prophetically observed with respect to Carlos DeLuna of Texas: “Once you institute the penalty, the bureaucratic machinery of death develops its own logic, and the system can be relied on to spare the beast-man, say, on a technicality of insanity, while executing the hapless Texan indigent who wasn’t able to find a conscientious attorney.” DM

Read more:

- Staking a Life, in Lapham’s Quarterly.

- Los Tocayos Carlos, in CHRLR website.

- Another innocent executed? in Salon.

- The wrong Carlos: how Texas sent an innocent man to his death, in the Guardian.