Maverick Life, Media, World

Colonel Doolittle’s Raid – 70 years later, still brave, still mad

The response to the attack on Pearl Harbor was something new. It was the first aircraft carrier-based, strategic air raid, designed to attack a distant nation’s homeland from the sea. In effect, it was the birth moment of strategic air power and doctrine. J BROOKS SPECTOR explores its meaning for its own time and for today.

When I first went to live in Japan, a Japanese journalist, first an acquaintance and then, later, a friend, gave me a small present. It was a book entitled In Peace Japan Breeds War.

The author of this small volume was Gustav Eckstein, a journalist who became a student of Japan in the 1920s, 30s and 40s. Eckstein wrote this book in the 1920s, considerably revising and reissuing it up to the midst of World War II. Eckstein had come to know those Japanese opposed to as well as those caught up in the imperial dream of conquest, which had increasingly infiltrated that nation through the 1930s.

Over time, I came to see the message implied by this gift was to give a fuller sense of the streams of thinking in a country that is usually better known for its lock-step unanimity of thinking and acting – all those stereotypes of robot-like businessmen and engineers conquering the world with Walkmen and Trinitron TVs. This was the country that more popularly lived by the folk saying “The nail that sticks up is hammered down.”

This unassuming gift became an essential part of my library on Japan, beside varied histories of the country, guides to its religious practices and artistic traditions, narratives of the World War II experiences of the peoples and armies of both nations, and a biography of Admiral Isoroko Yamamoto.

A career naval officer, he had been posted to the Japanese Embassy in the US as an Assistant Naval Attaché early in his career. Rising fast, he became the senior officer entrusted with the task of planning the combined naval/aerial attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, the main American naval base in the Pacific.

The core idea in Yamamoto’s plan was to deliver a shattering blow to American forces through a sudden, unexpected strike. This would paralyse resistance to a crushing wave of Japanese conquests through Southeast Asia, threaten Australia, and allow the Japanese navy to advance across the Pacific from forward bases in the Marianas, islands Japan had gained after World War I from a defeated Germany.

Once these elements had been achieved, the Japanese would be able to attack, surround and defeat the remaining US and British forces in a decisive sea battle that both sides’ planning staffs had been anticipating for over three decades. Yamamoto designed his plan perfectly, and in part he drew on lessons from the successful British raid against the Italian navy based at Otranto, earlier in the war.

Given their assumptions about the limited capabilities of the Japanese, American military commanders had no expectation of an air attack on the ships and planes based in Hawaii. As a result, all were positioned close together, either on the airfields, wingtip to wingtip, or adjacent to one another in Pearl Harbor’s sheltering quays, the better to defend against the expected saboteurs or even attacks by submarines entering the harbour. No American commander expected a combined naval air assault that would arrive undetected after crossing thousands of kilometres of open ocean.

Nevertheless, when the hammer blow struck, the US fleet was crippled, except for the two carriers that were out at sea on training drills. There never were any saboteurs, but a couple of Japanese midget subs appear to have carried out scouting and monitoring missions that totally eluded the submarine nets of Pearl Harbor’s defences.

Ironically, Yamamoto was found in near despair in the wake of his greatest tactical military triumph. He had promised his seniors a two-year window of time in which they could achieve strategic superiority in the Pacific against the Americans. But, upon hearing that the attack he had planned so meticulously had gone so well, instead of celebrating, he wrote in his diary and told close friends that he believed the victory had simply awakened a sleeping giant that would, in the end, hammer down the Japanese.

In America, Pearl Harbor had a harrowing result. Panicked citizens prepared for the seemingly inevitable invasion by an implacable, undefeatable Japanese military, a thoroughly frightened American government rounded up many thousands of American citizens of Japanese origin, together with Japanese nationals who were long-time residents and forcibly removed them all to camps located deep in the sparsely settled rural expanses of several Rocky Mountain and Great Plains states.

The US military then concentrated on contingency plans that would pull back US forces to the California coast, and then prepare for worse. US forces, along with British, Australian and Dutch forces, were driven from Malaya, Singapore, the Dutch East Indies and the Philippines. Together with continuing German victories in Europe and North Africa, even congenital optimists could easily be appalled about what the future would bring.

In the midst of this doom and gloom, a thoroughly stunned military was called upon to devise a strategic counterstroke that could somehow boost American morale and carry the war – at least in some small way – all the way back to the Japanese home islands.

The resulting plan, devised by Army Air Force Lt Colonel James Doolittle, was to put a squadron of B-25 bombers on the US aircraft carrier Hornet (called Shangri La to confuse Japanese intelligence that might be listening into US military traffic). The carrier would sail to within a thousand kilometres of the targets and then launch the planes from the flight deck to attack land targets in Japan’s major industrial cities like Tokyo, Osaka, Kobe, Nagoya and Yokohama.

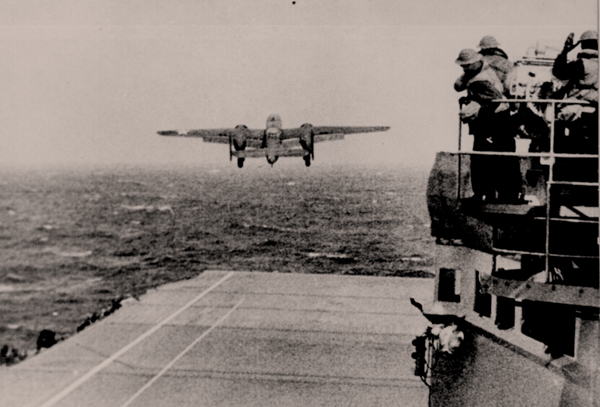

Photo: A B-25 taking off from Hornet for the raid. U.S. Navy photo.

These bombers were actually land-based planes with more payload capability and range than any then-available carrier planes – there were as yet no strategic bombers – and the crews were specially trained to take off from the deck of the carrier, a distance much shorter than their usual land runways. The planes were modified to carry enough fuel to reach their targets and then fly on to landing sites in Chinese territory not yet conquered by the Japanese military.

Describing this raid, the New York Times explained that “Never before had planes the size of B-25s taken off from an aircraft carrier and, to make that feat possible, the Doolittle raider planes were stripped of armament; they were also equipped with additional, rubber-fuel tanks to make the long flight to Japan. The pilots, all volunteers, had to learn to take off at 60 miles an hour rather than 90 and in one-third of the B-25’s usual takeoff distance.”

“The planes were supposed to take off from the Hornet 400 miles from Japan, but when a Japanese fishing vessel sighted the carrier, the schedule had to be accelerated, and the take-offs from the storm-tossed deck occurred 620 miles from Japan. The Hornet then sped away to evade retaliation. The planes crossed the Japanese coast barely 30 feet above the ground…”

The raid actually caused relatively little military-related damage to its targets. All 16 planes were lost to further service, some crews were captured, a few crew members died and one plane actually had to land in the Soviet Union, where its crew was interned for several years.

(The Soviets were neutral in the Pacific war until mid-August 1945. Years later, it was discovered that the B-25 held by the Russians could have made a significant contribution to Soviet efforts to develop their own strategic bomber, the Tupolev or TU-4.)

But the impact on Japanese military leaders and the government was electric.

Doolittle’s obituary in The New York Times recalled that “Sixteen B-25s, normally land-based but this time launched from the pitching deck of the aircraft carrier Hornet 620 miles off Japan, dumped tons of incendiary bombs on military and industrial targets in Tokyo, Yokohama, Kobe, Nagoya and Osaka.

“The assault, which made its leader perhaps the first genuine American hero of World War II, did much more than lift the nation’s spirits. It also demonstrated that the enemy was vulnerable to attack, and, more important, it left open a threat that a raid could recur, a threat that forced Japan to take defensive measures that proved exceedingly costly.

“The Japanese had been complacent in their belief that the United States, with much of its fleet rusting at the bottom of Pearl Harbor, possessed no striking power. The war was far away and going well for Japan.”

A Japanese carrier task force that had been roaming virtually unopposed in the Indian Ocean was quickly recalled to protect the homeland in the event of further, future raids. Squadrons of top-line fighter craft were similarly transferred away from the battles in the Southwest Pacific. In the end, these reassignments had a baleful effect on Japanese force strength for the conquest of Guadalcanal, and then, more decisively, the Battle of Midway.

Doolittle received the country’s highest military decoration, the Congressional Medal of Honor. His citation read: “With the apparent certainty of being forced to land in enemy territory or to perish at sea, Colonel Doolittle personally led a squadron of Army bombers, manned by volunteer crews, in a highly destructive raid on the Japanese mainland.”

Years later, in 1983, at a ceremony at West Point where he received another award from the military academy, Doolittle recalled the raid “was important to morale both here and in Japan, because the raid brought it up here and destroyed it there.”

In the long run, this raid, together with the lessons absorbed by the world’s militaries from the effects of the attack on Pearl Harbor, became the death knell for the battleship as the measure of naval strength. It also marked the beginning of increasingly large-scale strategic bombing to cripple war production far from battlefields.

And, most ominously, it also gave military planners a way forward in thinking of long-range air attacks as a strategic quantum leap in force projection. In the nuclear future that would soon come, this became the forerunner of the deterrence triad of nuclear ICBMs, submarine-based missiles and long-range bombers equipped with cruise missiles.

Seventy years later, only five veterans of this raid are still alive – they continue to hold periodic reunions, but the number of tables needed for the dinner has now, finally, dwindled down to just one small card table. Doolittle himself died nearly 20 years ago, at the age of 96, honoured and remembered.

As for the raid itself, it has been immortalised on film twice, first in Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo with Van Johnson and Spencer Tracy, and then more recently in Pearl Harbor with Ben Afleck and Josh Hartnett.

The 1944 film featured actual war footage that, even in this age of computer-enhanced film graphics, remains gripping and astonishing. In fact, in some ways it seems even more dramatic than the extraordinary CGI effects in the newer film.

The first film became a great morale booster for the US population during the war, helping drive the idea of the need to “finish the job” to defeat the Axis armies, just as Casablanca, two years earlier, had helped crystallise American determination for – finally – joining the fight against Japan, Germany and Italy.

But there is one astonishing footnote to all this. A few years ago, I heard from Japanese acquaintances that, when Pearl Harbor was shown in Japanese cinemas, the audiences cheered loudly: for the American stars, their planes and their aerial heroics. DM

For more, read:

- James Doolittle, 96, Pioneer Aviator Who Led First Raid on Japan Dies in The New York Times.

- Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo,’ a Faithful Mirror of Capt. Ted Lawson’s Book, With Van Johnson, Tracy, at Capitol, at The New York Times (the original 1944 review).

- How America ‘Struck Back’: Doolittle Raid Turns 70 at National Public Radio’s website.

Photo: Orders in hand, Navy Capt. Marc A. Mitscher, skipper of the USS Hornet (CV-8) chats with Lt. Col. James Doolittle, leader of the Army Air Forces attack group. U.S.Navy photo.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider