Maverick Life, Media, World

WikiLeaks turns WikiSpeaks: Assange the talk-show host

The first episode of international whistle-blower Julian Assange’s new talk show, The World Tomorrow, aired on Tuesday night on Russian TV. REBECCA DAVIS watched it and was underwhelmed.

Let’s get one thing straight: Julian Assange is no David Letterman. In fact, from a verbal perspective, he’s barely a David Beckham. What he does have on his side, however, is his reputation as an iconoclastic rebel, socking it to The Man. It is presumably this particular cachet that allowed Assange to land an absolute doozy of a first guest for his inaugural show: Hasan Nasrallah, Secretary General of Hezbollah, who hasn’t given an interview to the West since 2006.

It is probably also Assange’s reputation for rule-breaking that persuaded the Sri Lankan/British hip-hop artist M.I.A. to write music to open and close his show. M.I.A. (real name Mathangi Arulpragasam) is herself no stranger to controversy: her political statements about Sri Lanka and Palestine have been inflammatory enough to see her placed on a restricted access list when trying to enter the USA.

So it’s Rebels R Us over on Russia’s RT network, the English-language broadcaster set up by one Vladimir Putin in 2005 to help with Kremlin propaganda-pushing. This might seem like an odd broadcasting home for Julian Assange, but there are a couple of theories about why he agreed to host a show for them.

The first is that Assange is in serious need of some positive PR. Hezbollah and M.I.A might hold him in esteem, but the fact is that a lot of the rest of the world now sees him as a bit of a nutbag, a paranoid, narcissistic man who may also be a sex offender. If he can get through these shows without ranting about everyone who’s trying to destroy him, and without groping any women, it can only benefit him.

The second is that Assange needs the money and is okay with becoming the Kremlin’s stool pigeon in order to receive it. This is very much the theory of The Guardian, which termed Assange a “useful idiot” who joined the “long dishonourable tradition of western intellectuals who have been duped by Moscow”.

How was it possible, the paper asked, that the world’s most famous whistle-blower “should team up with an opaque regime where investigative journalists are shot dead (16 unsolved murders) and human rights activists kidnapped and executed”? The newspaper described his decision to do so as “strange and obscene”.

The third theory, though, is that the Kremlin’s anti-American sentiment actually dovetails very neatly with Assange’s own. He may be allowing this ideological symmetry to outweigh any other considerations, bent on revenge towards a government he sees as his enemy. Hezbollah and Washington are not the best of friends, to say the least. If his future guests go on to include a who’s who of what America considers global undesirables, this will be very telling.

Tuesday’s first episode of The World Tomorrow opened with a voice-over intoning “I’m Julian Assange”, suggesting that what was to follow was to be personality-driven journalism. As it turned out, the viewer would have been grateful for anything remotely approaching a personality. Assange’s accent is still Australian but bears the traces of his years in the UK. It’s brittle and clipped. This is not an Aussie you can imagine enthusiastically exhorting you to “chuck another shrimp on the barbie, Sheila!”

“We’ve exposed the world’s secrets,” the voice-over continued. “Been attacked by the powerful…” Cut to footage of Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama denouncing WikiLeaks “For five hundred days, I’ve been detained without charge. But that hasn’t stopped us.” Footage here becomes highly reminiscent of the viral Stop Kony video and generic scenes of protest. “Today we’re on a quest for revolutionary ideas that can change the world tomorrow.” Close-up of Julian looking pensive.

“This week, I’m joined by a guest from a secret location in Lebanon.” Julian is busy underlining things on a piece of paper, possibly the printed out Wikipedia entry for Lebanon. “He is one of the most extraordinary figures in the Middle East. He has fought many armed battles with Israel and is now caught up with the international struggle for Syria. I want to know, why is he called a freedom fighter by millions and, at the same time, a terrorist by millions of others. This is his first interview in the West since the 2006 Israel-Lebanon war. His party Hezbollah is a member of the Lebanese government. He is its leader, Hassan Nasrallah.”

It is hard to convey just how robotic Assange’s delivery is. His words sound like they have been grafted together in random chunks by voice simulation software. Nothing about what we see is telegenic: not Assange, with his weird, prematurely-whitened locks and crumpled shirt, nor the setting, which looks like a desk in a poky municipal boardroom.

It didn’t help that the interview with Nasrallah was conducted via Skype from Assange’s house-arrest cottage in Norwich to whatever cave in Lebanon the Hezbollah leader is currently stowed away in, or that every question had to go through an interpreter. Said interpreter had a posh English accent, which made him sound exactly like Richard Dawkins.

Nasrallah, throughout the interview, appeared far more natural and at ease than Assange. He was very cuddly looking for a militant leader, sporting a pinkie ring. It was difficult to imagine him rousing a stadium to arms with his words. He had every reason to feel comfortable: at no point during the half-hour interview did Assange even come close to putting him on the spot or questioning any of his answers. Assange did the classic amateur journalist thing of not asking any follow-up questions based on the answers given, instead sticking slavishly to a list of prepared questions.

Some of these questions were so soft that they amounted to a testicular fondle. “As a leader in war, how did you manage to keep your people together under [sic] the fact of enemy fire?” Nasrallah must have been trembling in his combat boots. “When you were a boy, you were the son of a greengrocer. What was your first memory?” Come on Julian, you’re interviewing the leader of one of the most controversial organisations in the world, not a contestant on Pop Idols.

Even questions that started off seeming tough soon dissolved into a whimper. Assange brought up the fact that WikiLeaks cables revealed Nasrallah’s unhappiness with growing corruption within Hezbollah, with members driving around in SUVs, wearing silk robes and buying takeaway food (there doesn’t seem to be an Arabic translation for “takeaway food”, incidentally, unless Nasrallah’s interpreter was just a bit rubbish). But then Assange concludes, with an under-arm lob: “Is this a natural consequence of Hezbollah moving into electoral politics within Lebanon?”

Interestingly, Nasrallah’s response to this was that the “rumours” contained in the WikiLeaks cables were not correct and “part of the media war against us”. In essence, he was casting aspersions on the source: WikiLeaks. If I were the founder of WikiLeaks, I might have an interest in taking him up on that point. But not our Jules.

The only moment of toughness Assange showed was in questioning on Hezbollah’s relationship to Syria. Hezbollah and the regime of Bashar al-Assad are thick as thieves – coincidentally, much like Moscow and Assad’s regime. But Assange brought up the death toll in Homs and dropped in the fact that he had dined with deceased journalist Marie Colvin before her death. Nonetheless, he was at pains to stress that he understood Hezbollah’s position, and their desire not to see Syria torn apart by civil war.

Nasrallah claimed that he personally had found Assad “very willing” to carry out “radical and important reforms”. This should be front-page news for the rest of the world, who must just not be looking hard enough for evidence of these promising reforms. Nasrallah also claimed that opposition groups in Syria had turned down Hezbollah’s requests for dialogue. Assange did not push him on either of these assertions.

The hands-down cringiest moment of the interview came when Assange decided to lighten the mood a little. “I read a rather amusing joke of yours about Israeli encryption and decryption,” he says, his voice as flat and expressionless as ever. “Do you remember this joke?” If he wasn’t utterly non-threatening, the effect would be a bit like a maths teacher asking a giggling student to please “share what’s so funny with the rest of us”.

It’s not entirely clear what the “joke” was, but Nasrallah explained that Hezbollah operatives are able to outwit Israeli security listening in on their walkie-talkie conversations by using slang from the villages about “the cooking pot, the donkey, the father of the chicken”, which is unintelligible to the Israelis. “That’s not going to do you any good in WikiLeaks, by the way,” Nasrallah added, and he and Assange broke into guffaws. All very cosy.

The USA got a few mentions, as you’d expect. Assange brought up the fact that the US blocks access to Hezbollah’s international media network, and then delivered another little interrogative gift. “Why do you think the US government is so scared of Hezbollah?” Nasrallah’s response was predictable, namely that the US government doesn’t want people to hear anything that would disrupt Washington’s presentation of Hezbollah as a terrorist organisation.

Assange’s final question was an interesting one, however, and perhaps a hint that the talk-show series might develop into something more promising. “You have fought against the hegemony of the United States. Isn’t Allah, or the notion of a God, the ultimate superpower, and shouldn’t you, as a freedom fighter, also seek to liberate people from the totalitarian concept of a monotheistic God?” However, the question seemed to tickle Nasrallah, who was adamant that there was no conflict in his position. Resisting US hegemony, he said, was “a moral issue, and an instinctive one, and a human one” – a cunning piece of rhetoric that, since it implicitly places the US as being immoral, unnatural and inhuman by contrast. The Kremlinites must have been rubbing their hands with glee.

And that was it. Assange thanked Nasrallah, gave an excruciating sort of half-embrace to his interpreters, and the credits rolled. Their gimmick: all the names were blacked out, like a redacted WikiLeaks cable. If only The World Tomorrow was half as edgy as it likes to think it is. DM

Read more:

- The Prisoner as Talk Show Host, in The New York Times.

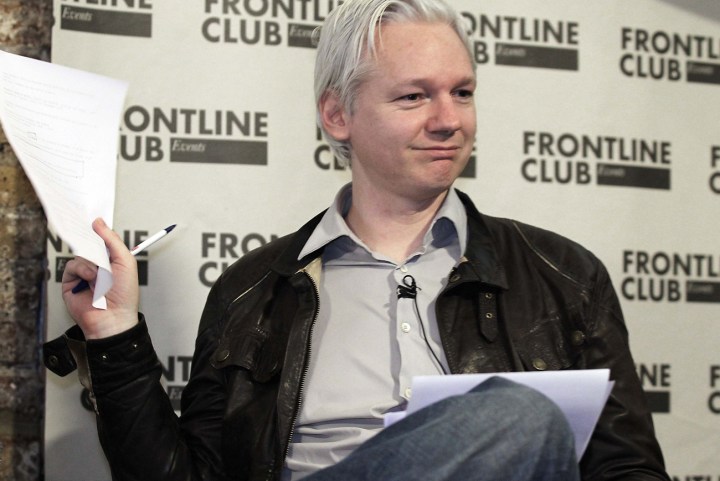

Photo: WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange holds a document containing leaked information at a news conference in London, on 27 February 2012. REUTERS/Finbarr O’Reilly.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider