Eugene Terreblanche's killer hit and hacked the AWB leader's body 28 times. His skull was crushed, his face destroyed, his ribs broken and his liver ruptured.

But the farm worker who admitted beating Terre'blanche to death has decided not to reveal what drove him to pick up an iron pipe and to hit his boss of eight months again and again. And again.

Chris Mahlangu's testimony would have been the stuff of a tabloid writer's dreams.

The slightly built father of one claimed through his lawyer that he had been a repeated victim of Terre'blanche's secret homosexuality: sodomised at least four times by the man whose cattle he’d tended. The last sodomy incident had happened, his lawyer told the Ventersdorp High Court, on the day of Terre'blanche's murder.

While Terre'blanche's family vehemently denied any suggestion that he would ever have had sex with a black man, the state could not outrightly disprove Mahlangu's claims. For reasons that have yet to be explained, a semen-like substance clearly visible on Terre'blanche's genitals in crime scene photographs was absent when his autopsy was conducted.

The mysterious substance – and it's equally mysterious disappearance – was manna from heaven for the defence. It was proof, they argued, that police were so intent on framing Terre'blanche's murder as a "farm killing" that they ignored or deliberately removed any evidence that could show the murder had a far darker motive.

The prosecution tried to undermine this argument by calling mortuary manager Gladys Lesenyego to testify about the removal of Terre'blanche's body from the crime scene. But, five minutes into her cross-examination, Lesenyego conceded that someone must have removed the semen from Terre'blanche's body during the two hours she was ordered to stay outside his bedroom.

Terre'blanche's brother, Andries, says he is unhappy about the way in which the police handled the murder investigation.

"I believe there were mistakes, there were things that went wrong... the evidence from the police was very ambiguous. A person can't pinpoint who exactly is responsible but I believe it wasn't handled properly from the beginning."

Andries Terre'blanche attended every day of Mahlangu's murder trial, shaking his head and muttering every time Mahlangu's advocate, Kgomotso Tlouane, revisited his client's sodomy claims. He believes Mahlangu's evidence may have revealed the political motive that he is convinced drove his brother's killing.

"I'm very disappointed that Mahlangu couldn't say what happened because I'm convinced that Mahlangu would have come out with a lot of things that are now hidden, that we won't know."

Mahlangu's silence now ensures that his claims of sexual and physical abuse remain untested and therefore can't be relied upon by the court in reaching its verdict. But it also has deeper implications for his teenage co-accused: it almost ensures he will be acquitted.

Investigating officer Tsietsi Mano conceded during his cross-examination that there was no forensic evidence linking the 17-year-old to the murder. No fingerprints placed him on the scene of the crime and not a single drop of Terreblanche's blood was found on his clothing or his white rubber boots.

Andries Terre'blanche says he cannot accept the now almost certain prospect of the teenager's acquittal.

"I can give you the assurance that if the little one is acquitted, we will definitely go on appeal. The little one was there... He went with Mahlangu and boasted about killing Terre'blanche and said we are now the bosses of this farm.

“I feel unhappy, really. I don't think that this can be right... He was part of the murder."

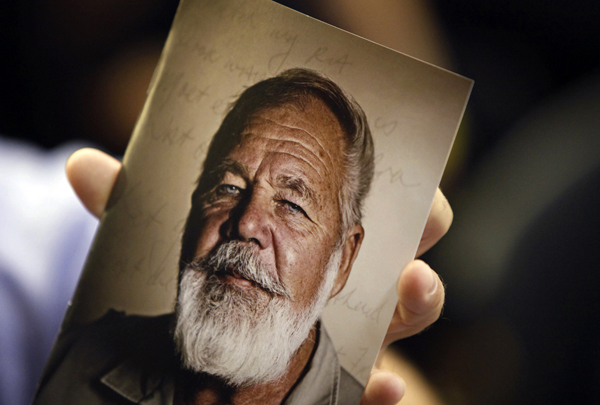

Photo: A supporter of Eugene Terre'Blanche holds his picture during his funeral in Ventersdorp in South Africa's North West Province April 9, 2010. REUTERS/Siphiwe Sibeko.

While robbing the South African media of at least two days' worth of salacious headlines, the defence team's decision to keep Mahlangu and the teenager out of the witness box is legally astute and, according to the lawyers themselves, rooted in a genuine desire to protect their clients.

"It's not a pity, it's not a pity at all," the teenager's lawyer Zola Majavu tells me.

"If either of them were to go into the box, we were going to unleash them, illiterate and uneducated, innumerate as they are, to a flood of questions and the sophistication of a highly experienced prosecutor.

"We felt it would just be a continuation of the injustice that we feel has been perpetrated against our client. They are mindful of the risks, but we do believe that it was the correct decision and the correct tactical move that we made. After all, they are under no duty to tell the court or the world what really happened... If anything, the Constitution preserves their right to remain silent."

I ask him if it's a foregone conclusion that the teenager will walk free after Judge John Horn gives his ruling on 22 May, exactly a month after the youngster, who was 16 when the murder was committed, turns 18.

"It'll be irresponsible to say that. But I will sleep better tonight," he says.

While it now seems unlikely that the true motive behind Terre'blanche's murder will ever be explained, Mahlangu's latest – and arguably most absurd – explanation is telling. He initially told police that he and the teenager had been plied with 30 bottles of Savannah by Terre'blanche, who had promised to pay their R650 monthly salary on the day of his murder. He claimed in a statement that Terre'blanche had reneged on that promise after finding three of his cows were missing, blaming Mahlangu and the teenager for the loss.

After drinking his Savannahs with the teenager at a neighboring farm, and inflamed by Terreblanche's refusal to give him the money that would allow him to go home, Mahlangu told police he decided to kill his boss. He and the teenager broke into Terre'blanche's farm house, found him sleeping in his bed and beat him to death with an iron pipe. He wanted to castrate Terre'blanche, he said, but thought better of it.

Tlouane sought to undermine this damning series of statements when he presented Mahlangu’s final version of events to the Ventersdorp High Court. He claimed that Mahlangu had not forced his way into Terre'blanche’s house with the intention of cold-bloodedly hacking his sleeping and elderly boss to death in bed.

Instead, Mahlangu’s lawyer framed him in the language of an abused woman who has, finally, had enough.

Mahlangu, he said, had gone to the Terre'blanche home to search for his suitcase. Like a battered wife making her escape, he wanted to make a run for it. And then, as he told the court through his lawyer, he was confronted by the angry Terre'blanche.

“He tried to escape through the dining room and he could not… and so he ran back to the bedroom,” Tlouane said, explaining that Mahlangu reached for an iron pipe – which was lying on the floor of Terreblanche’s bedroom – when it became apparent that he could not get away.

Mahlangu had not meant to kill Terre'blanche, said Tlouane, but he had no choice.

The story is far-fetched and totally unsupported by the blood-spatter evidence in Terre'blanche’s bedroom, where he died almost instantly from the powerful blows rained down on his head.

But it says something far more interesting about the man who looks certain to be convicted of his murder. It is the story of someone who wants to be seen as a victim, and who actually may have been one.

Mahlangu has made his escape from the man he says abused him. He no longer hides his face from the cameras that track his every exit and entrance from the court where he is being tried. Farm workers stand outside court bearing placards with the words “rot in hell Terre'blanche” and applaud the police truck that carries him to jail. He’s dressed in new clothes and has converted to Islam.

Mahlangu eats wine gums as he walks out of court after closing his case, picking out the red ones as he lumbers towards the court doors.

I ask him how he feels and he smiles.

“I’m okay,” he says.

They are the only two words I have ever heard him utter. And, after two years of covering the Terre'blanche murder, I still have no idea what lies beneath them.

It’s unlikely we ever will. DM

Photo: Chris Mahlangu, one of two suspects in the murder of white supremacist and Afrikaner Resistance Movement (AWB) leader Eugene Terre'blanche, looks on during his appearance at a South African court in Ventersdorp, in the North West Province, on 10 October 2011. REUTERS/Siphiwe Sibeko.