Maverick Life, Media, World

At last, Ziggy Stardust gets a seat next to Lord Byron

Initiated in 1866, London’s blue plaques still say as much about the city as Hollywood’s Walk of Fame says about Los Angeles. So how do we interpret the British capital now that a fictional transvestite alien has been commemorated alongside its greatest poets, philosophers and explorers? By KEVIN BLOOM.

Say what you want about the city in winter – those cold and lightless days when your shoulders are bunched up around your ears and your eyes are focused only on your shoes – but to walk through central London between late May and early September is to be fully immersed in its historical context. For instance, what did Mile End Road smell like in the 1770s, when Captain James Cook returned to his house on the street after yet another voyage to the dark corners of the earth? What were the people on Tavistock Square wearing in the 1850s, when Charles Dickens was writing Bleak House in his office a short walk from the park? In 1849 in Westminster, did Herman Melville stop to tell anyone on Craven Street about the trouble he was having turning a whale into a believable character in his new book?

During the summer months in London, you ask questions like these because it’s impossible – unless you’ve got the cultural sensibility of a housefly – not to notice the commemorative blue plaques. The idea for these markers, which today number over 800, was first proposed by a House of Commons MP in 1863, and was implemented by the Society of the Arts three years later. The first sites considered for commemoration were buildings that Benjamin Franklin and Lord Nelson had once occupied, but the inaugural honour went to 24 Holles Street in Cavendish Square, Lord Byron’s birthplace. From the outset, the idea was to establish the link between London’s buildings and the great names that had lived or worked in them. In 1901 the city’s local council took over the project, and 85 years later it was handed to English Heritage, who’ve recently noted on their website:

“English Heritage has continued the work of the GLC in broadening the coverage of the scheme, both geographically – there are now plaques in all but three of London’s boroughs – and in terms of the figures commemorated. English Heritage plaques honour individuals from a wide range of endeavour, such as the guitarist and songwriter Jimi Hendrix, Ian Fleming, the creator of James Bond, and the actress Vivien Leigh, as well as people such as the poet, Lord Tennyson, the pilot Guy Gibson, and the nurse Edith Cavell.”

This week, just off London’s Regent Street, Ziggy Stardust got a blue plaque too. Yup, that’s him, the left-handed guitar player who jammed with Weird and Gilly and the Spiders from Mars. He isn’t the first fictional character to receive the honour – there’s a plaque on Baker Street commemorating Sherlock Holmes – but that doesn’t make the break with tradition any less noticeable: far more people have mistaken the detective for a real historical figure than have ever believed Ziggy to be something other than David Bowie’s alter-ego. So while London’s conservatives have been asking themselves whether the staff at English Heritage have finally gone mad, the left-leaning writers at The Guardian have accepted the task of explaining why the commemoration is a just and noble act.

“Perhaps only someone who felt he was playing a role could have had the courage to make that step at that moment in time,” noted Dorian Lynskey on Tuesday, 27 March. “The gay rights movement was in its infancy, homosexuality had only been legalised a few years earlier, and even Liberace was still publicly denying the rumours. And unlike a thoroughly gay star, Bowie had plenty of room for manoeuvre: the freedom of a born actor who could assume and discard roles as he wished. But the significance of Ziggy’s sexual ambiguity transcended both Bowie’s media games and the glam rock scene that he (and the similarly androgynous Marc Bolan) spearheaded. Many of the schoolchildren whose minds were blown by that performance of Starman grew up to be key players in the genre-blurring pop of the early 80s. When gay stars such as Boy George, Marc Almond and Holly Johnson shared the top 10 with straight men in eyeliner, it wasn’t always clear which was which.”

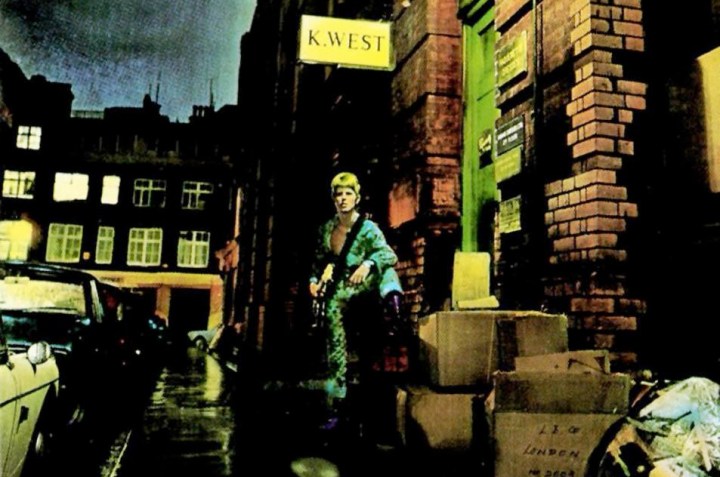

At the time that Ziggy appeared on the cover of the eponymous album, a shot taken of Soho’s Heddon Street with the transvestite alien hero perched on a bin, the real David Bowie was married (to a woman) and a father of one. What the plaque is commemorating, then, is the blurring of the lines of sexuality; the awakening in mainstream Western culture that beneath and between the categories of entirely straight and entirely gay is a more authentic continuum that connects the two. For introducing that truth, Ziggy certainly deserves his/her blue plaque.

Question is: where to next for the fine folk at English Heritage? So far, the suggestions have covered everyone from Paddington Bear to Ebenezer Goode. DM

Read more:

- Ziggy Stardust – it was all worthwhile, in The Guardian.

- History of the Blue Plaques Scheme.

Photo: David Bowie’s alter-ego – Ziggy Stardust – has been honoured with a blue plaque.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider