Media, South Africa

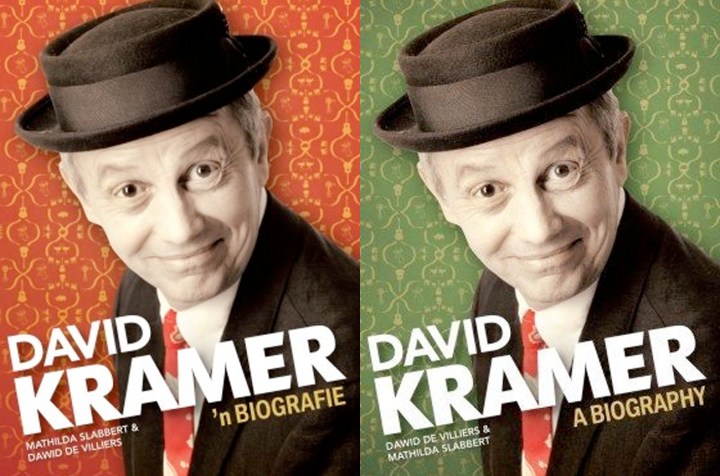

Kramer biography fixed in literary amber

Wits musicologist MARIE JORRITSMA takes a sharp look at Dawid de Villers and Mathilda Slabbert’s biography of David Kramer, probing the limits of its “authorised” status and its strongly literary, rather than musically interpretive, approach.

“Who is the man behind the guitar and the red vellies?” This is the question posed on the back cover of David Kramer: A Biography. However, after reading this book, I’m not convinced the reader is any the wiser. As the authors themselves state in the preface, the book has aspects which may “strike the reader as idiosyncratic”. These “idiosyncrasies” manifest in the fact that the work “is generally silent on the subject’s domestic and family life, and also tends to deal quite sketchily with the business and production side of his career”. While the authors obviously respect the subject’s desire for privacy, these decisions lead to tangible omissions in the biography.

The structure of the book betrays this approach, where the chronology of Kramer’s life and works is detailed systematically, but additional interpretive and critical information on more controversial issues are conspicuously absent. After a brief preface in which the authors outline their approaches to the work, the prologue provides the genealogy of the Kramer family. Thereafter, the book is structured in five sections which correspond generally to a chronological account of Kramer’s life, but focus particularly on the works generated by each period.

Section I deals with his early life and artistic influences, Section II begins with his compulsory military service and then discusses his period of study in Leeds, Section III focuses on his singer-songwriter career during the 1970s and 1980s, Section IV’s topic is Kramer’s collaboration with Taliep Petersen and Section V resumes the discussion on the artist’s solo career and focuses in particular on the Karoo Kitaar Blues productions. Each section affords the authors the opportunity for discussion of the various poems, writings, music albums, live performances and musicals that constitute the output of this well-known South African icon.

The information presented is generally well written and researched, although there is little direct speech which would have resulted in a livelier text. The main sources are the Kramers themselves (Renaye, David and his brother John, the family archivist) who provided the authors with important primary documents regarding Kramer’s life and career as well as various audio interviews. Additional sources include the many media articles on Kramer’s artistic endeavours, the reader soon obtains a helpful sense of the newspaper and magazine discourse surrounding Kramer’s work.

While the authors thank various people in the preface who discussed their interactions with Kramer, these interviews are unfortunately rather sparsely integrated into the text. This results in a prominent reliance on the Kramer family perspective in this book. When a biographer is fortunate to have a live subject who is willing to supply input as well as archival material, this certainly provides a rich foundation on which to compile the text. Unfortunately, the Kramer presence in this case does not allow the authors to move beyond a certain point in their critical approach to their subject and this results in an account which often precludes a deeper interpretive commentary.

One example of this is the discussion of albums within the text. These generally begin with a detailed description of the album cover, what it symbolises, the details about when the music was first written or subsequently revised, and then some excerpts of lyrics with brief explanations of their meanings. These tend to paint Kramer as a lyricist supreme who is an expert on providing a sudden twist in the tale towards the ends of songs.

Although the authors mention their preference for the literary studies aspect of this biographical subject in the preface, the absence of musical detail remains a problem with these discussions. Besides faithfully mentioning each musician (and his/her instrument), who played on the album, and some fleeting comments on the accompaniment provided to these lyrics, there is very little discussion of the music behind the songs. Even if the authors did not feel qualified to examine musical issues in depth, the discussion of albums would have benefitted immensely from interviews with the musicians themselves. They would have offered information about how Kramer worked in a studio situation, how the music was conceived, what levels of collaboration were used in the recording and production process, among other interesting questions. Unfortunately, the authors’ decision to keep the information on the business and production side “sketchy” has affected the text in quite a profound manner.

The matter of Kramer’s “invaluable contribution to the field of South African ethnomusicology” should also be discussed further. I am aware of the Karoo Kitaar Blues CD and documentary of the same name and regard them as extremely useful resources. However, I would classify these as a contribution of a complex musical case study which encompasses the themes of race, class, gender, politics, domination, resistance and agency. Nowhere does Kramer explore these themes in written form as part of a scholarly contribution. Rather, the musicians’ original compositions are showcased in a concert format with Kramer as presenter/collaborator.

Kramer prefers to liken this project to one undertaken in the 1930s by the folklorist, Alan Lomax. The emphasis of Lomax’s work is clearly on collection and preservation, which Kramer echoes in his statements about this “almost forgotten” music. In contrast, contemporary ethnomusicology emphasises interpretation, within specific cultural contexts, of particular music styles and/or genres. Thus, Kramer’s contribution with these releases adds to our knowledge and awareness of a certain genre of music, but does not provide critical written interpretation or the reflexive approach which is the mark of ethnomusicology today.

In addition, the way in which concerns about exploitation of the Karoo Kitaar Blues musicians is dismissed in the text would not be regarded as a valid ethnomusicological approach; instead a transparent explanation of the processes involved would be more fitting. Unfortunately, the text shuts down any possibility for critical discussion in this regard by insinuating that anyone who raises these issues is implying that people of different races and classes should not be allowed to collaborate. This statement completely misses the point that there are almost always issues of power inherent in these kinds of collaborations and instead of closing the debate entirely, these should rather be openly discussed as part of the production and dissemination processes. The fact that the Karoo Kitaar Blues CD is copyrighted to David Kramer remains an important topic for debate.

Despite these shortcomings, I am reminded that this is the first work of its kind on David Kramer and for this it deserves recognition and acknowledgement. This biography will open the way for other parties to conduct research on specific aspects of Kramer’s output and it provides useful background information for anyone interested in Kramer. Also, the book does make the point that there is a difference between Kramer’s “almal se pêl” persona and Kramer, the individual. The authors make this clear throughout the book and obviously remain faithful to Kramer’s own desire to make this clear to his fans. Although this book emphasises that there is a private individual behind the guitar and red vellies, unfortunately, to me, this person ultimately remained elusive. DM

© Stellenbosch Literary Project (SLiP), Department of English, Stellenbosch University. For other literary reviews, reports, blogs, translation and events, see www.slipnet.co.za.

ALSO on SLIPNET:

- Karin Schimke launches Bare & Breaking, a sensuous debut volume of poems, claiming the right to pleasure while ‘finishing one’s shit’.

- What’s Antjie Krog up to in Stellenbosch with “indigenous” musicians and poets?

- Listen to a riveting performance of Mongane Wally Serote’s famous love-hate poem, ‘City Johannesburg’, in a dual-language translation-original duo in English and Afrikaans.

Photo: David Kramer – A Biography. The first of its kind.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider