Media, South Africa

Mda’s ‘tell-all’ approach a bit much

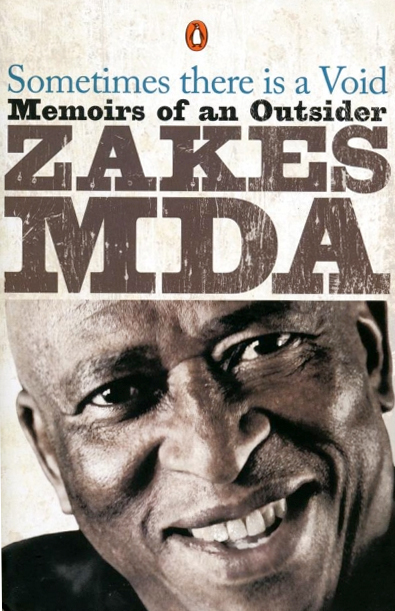

Sometimes there is a Void: Memoirs of an Outsider by Zakes Mda, Johannesburg: Penguin, 2011. Review by CHRIS DUNTON.

On the acknowledgments page of his autobiography, Mda quotes a senior South African editor’s query: “Are you not a little young to write a memoir?” This is an understandable query.

Nonetheless, there has been no shortage of dramatic incident in Mda’s life to date, much of it bearing significant political and cultural relevance. Also, if the virtue of distancing is a concern, at the outset of the book Mda establishes an ingenious and affecting narrative device that enables this. On the other hand, given the length of the book we wish he had followed the principle of judicious selectivity on a “need to know” basis.

The narrative opens with a tender, vivid account of a “pink mountain” in Eastern Cape, near the Lesotho border, where Mda has established a bee-keeping project. Mda guides his current wife through the ruins of his grandfather’s estate.

Like Achebe and Soyinka before him, he moors pointers to the adult future in the flow of childhood memories as he writes. He also tells the history of his clan of origin, where a highlight is the terrorising of a British colonial magistrate by paramount chief Mhlonte, which involves a theatrical performance – another link forward to Mda’s adult career.

There is the occasional jarring note. Mda acknowledges to his uncle that he now works as a professor of creative writing in the US: “Yes, I work there now. Just like the migrant workers who go to the mines in Joburg.” One baulks at that “just like”. Mercifully, as this very long book proceeds, there are few splinters of this kind; Mda’s overwhelming sensitivity is generally in command.

The focus in the back-narrative shifts to the late 1940s, to the role of Mda’s father, A P, as one of the founders of the PAC. It includes accounts of Mandela’s visit to the family house when he acted in a libel case for A P, accused of being a communist. A lovely story about the rescue of A P’s briefcase prior to a police raid is well paced and amusing, but in this packed narrative what comes next erases all smiles: Mda’s repeated rape by his nanny, which led to years of sexual dysfunction, and about which he was to keep silent for decades.

There is an extended portrait of the father, “guiding spirit of the PAC: his socialism and his anti-totalitarianism”. A P is up against his son’s school principal, Moleko, who proclaims: “There are those who think they can win against the white man. That is very stupid… What do you think a black person can do to make South Africa a better country?” With A P’s arrest and subsequent exile in Lesotho comes Mda’s loss of the world that these early chapters, with their ghosts and yearnings, commemorate.

During the Lesotho years there are increasing complications in Mda’s personal life. The account of secondary schooling gets bogged down in detail, but is enlivened by the story of Chris Hani helping a floundering Mda with his Latin, and by Mda’s incisive tracing of the Byzantine interrelationships between political parties in Lesotho, both national and South African ones in exile. Still, over-expansiveness is a problem with this book, especially in the section where Mda recounts his years of slumming it in Maseru. Reading this is like staying on at a bad party that’s gone on too long. Endearingly, he often addresses the reader directly: “you will recall that”, “a character you met some time ago” and “this is none of your business”. The reader may feel, however, that Mda might usefully have employed the logic of this last phrase more often.

The book perks up notably when it reaches the Lesotho crisis of the 1970s: Mda offers convincing portraits of the thuggish “Young Pioneers” (trained in Banda’s Malawi and later in North Korea) and of Fred Roach, the repugnant and aptly named British head of the murderous mobile police.

After a series of short-lived jobs and business ventures, he is employed at the National University of Lesotho, where he initiates his important work in theatre as a tool for development communication. However, his account of the university misses the opportunity to explore the triumphs and turbulence of a historically important, if perennially fraught institution.

As Mda travels back and forth between Lesotho and South Africa there are some memorable anecdotes, such as the apartheid police spraying protestors in Cape Town with purple dye, “giving birth to the slogan The Purple Shall Govern”. Years later, back in Lesotho and researching ritual theatre, he at one point disguises himself as an old woman to gain admission to an all-female birthing ritual – complete with ragged pantyhose. A sight one would have loved to have seen.

A poignant episode is a brief rift between Mda and his father, following an assertion on the son’s plays in an essay that badly misinterprets A P’s politics. Mda defends his father by refuting the suggestion that A P’s Pan-Africanism was narrowly race-based: “It suffices to say my father’s Pan-Africanism was inclusive rather than narrow.”

There is the occasional clunker, such as the observation “I would rather be an artist than an academic. I would rather create than destroy others as academics are wont to do”. (Maybe Mda hasn’t tuned into some of the more virulent squabbles between American hip-hop singers or British novelists). Yet at the same time, he can be sharp and sensitive. There is an impressive section on gay rights. Mda abhors homophobia and is scathingly dismissive of the canard that same-sex sexuality in Africa is a western importation: “Ask American gays in the military and in states where they can’t exercise their human right to marry and be miserable like the rest of us.”

Mda’s commitment to the ideals of a free South Africa is affirmed throughout. Of the fresh waves of exiles into Lesotho in 1976, he records that “their performance poetry gave us goosebumps and assured us that we were marching towards victory in South Africa”. But he also comments in detail on why he now lives in the US, not at home. In South Africa, he argues, he can’t practice the skills in which he’s trained because of “the vast patronage system and crony capitalism that has emerged in my beloved country”. Being “too outspoken”, he has become marginalised at home. When his children apply for jobs, he warns them that it is better not to claim kinship with him. Mda’s concerns are later set out in detail as he reprints a letter he sent to Mandela in the late 1990s on corruption, nepotism, and what he sees as the danger of the new South Africa freezing into the kind of perma-corruption that bedevils Nigeria.

During an initial stint at his base in Athens, Ohio, he records the brutal 1982 raid on Maseru and the volte-face this brought about in Lesotho politics (he is good at limning the complexities of this). At the same time Mda gets involved in the campaign in the US to disinvest from South Africa. He recounts a quarrel with Athol Fugard over the validity of the cultural boycott and again the pragmatic issues and the ethics of this affair are thoughtfully dissected.

Time and again one is arrested by a plangent, lucid comment on guiding principles or on ideological formations. On vegetarianism, for example: “We can survive quite healthily on the non-sentient bounty of the earth, without visiting acts of violence on each other and on those creatures we deem to be of a lower order.” Or on Africa’s portrayal in the West: “that jelled narrative… [which] must not do anything that dishabituates established notions, but must reinforce the narrative that has congealed in the audience’s mind.”

The last fifth or so of the book is firmly anchored back in the personal, with an exhaustive account of Mda’s protracted and painful divorce and custody battles with his second wife. While this is an eye-opener for anyone who hasn’t been condemned to such an ordeal, we were left wondering if this were not perhaps more than we needed to know. However, despite these reservations about Mda’s “tell-all” approach to his life story, Sometimes there is a Void comes close to being a must-read. DM

© Stellenbosch Literary Project (SLiP), Department of English, Stellenbosch University. For other literary reviews, reports, blogs, translation and events, see www.slipnet.co.za.

ALSO on SLIPNET:

- Sonja Loots’s novel, Sirkusboere, gives the circus version of the Anglo-Boer War.

- Read a preview of a new English translation of Etienne Leroux’s famous ‘Sestiger’ novel, Sewe Dae by die Silbersteins.

- Poet Finuala Dowling challenges you to write a poem about mortality in her SLiPnet Poetry Project for March.

Photo: Sometimes there is a Void: Memoirs of an Outsider by Zakes Mda. PENGUIN.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider