Maverick Life, Media, South Africa

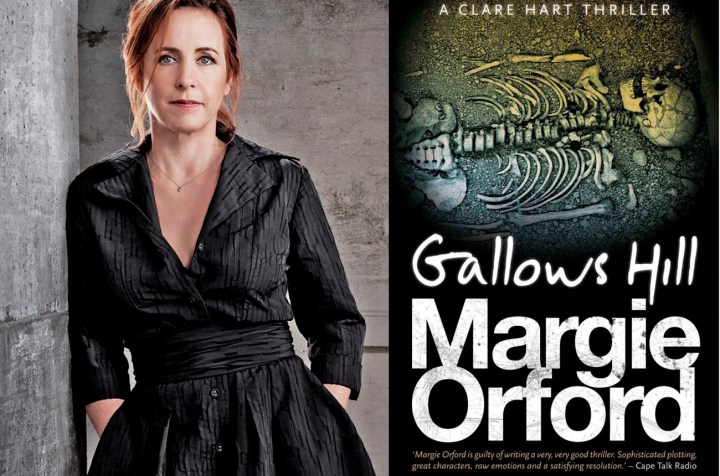

Murder she wrote: Margie Orford, SA’s crime fiction queen

Hard core critics might have a knife in for crime writing, which doesn’t have the literary appeal of a Franzen or a Vladislavic, but with heavyweight work coming from northern Europe and SA, it’s a little early to dismiss the genre just yet. MANDY DE WAAL looks at the realism of local thrillers and speaks to the first lady of crime lit, Margie Orford.

Sonntagzeitung crime reviewer Gunter Blank reckons that writing crime fiction is redundant in societies like the US, Germany and Sweden. In an email missive to Cape-based-journalist-cum-writer-cum-crime-novelist Mike Nicol, he lamented: “It has become pretty difficult finding a decent crime novel that’s not chewing up the same ol’, same ol’. I mean how many serial killers, people with troubled childhoods, old Nazi criminals, heists gone awry and adultery turned murder, can you invent to keep the genre fresh?”

Now Blank’s wrong about that place that’s colder than a witch’s tit. Not Blank’s home state of Germany, of course, which does get a trifle chilly. I’m talking about the upsurge in Scandinavian crime fiction which has shown the world that there’s a hell of a lot more to come out of the likes of Denmark, Sweden, Finland and Norway than Smilla’s Sense of Snow.

Nordic noir first appeared on our radars when the common-law wife and husband team of Maj Sjöwall and the late Per Wahlöö brought us the humourless Martin Beck. Hailed as one of the world’s first real detectives, Beck was also a literary device the writers employed, as Wahlöö said, to “use the crime novel as a scalpel cutting open the belly of the ideological pauperized and morally debatable so-called welfare state of the bourgeois type.” The world fell in love with Beck (didn’t mind the activist’s message that much) and the series sold some 10-million copies, mostly outside of Sweden.

More recently Henning Mankell answered the question “What the hell’s wrong with Swedish society?” by using a disillusioned detective called Kurt Wallander. The result was a series of crime novels that were translated into forty languages and which sold some 40-million copies, before Mankell retired the much loved, albeit grumpy, hero. Of course you can’t talk Nordic crime novelists without mentioning Stieg Larrson, the journalist and activist whose Millennium trilogy was published posthumously, and sold some 65-million copies worldwide.

Now, Klerksdorp’s a hell of a lot hotter and dryer than northern Europe, and computer hacker Lisbeth Salander is as far away from South African cop Benny Griessel as one could get, but like those Nordic countries South Africa is spawning its own front of crime writers. Cape-based wunder-krimi Deon Meyer is the publisher’s wet dream who’s leading the local charge.

Former Die Volksblad journalist and Griessel creator, Deon Meyer has made the world take notice of South Africa with crime novels that have been translated into 25 languages (including Danish, Norwegian and Swedish). What’s important about Meyer’s work is that it has elevated literary opinion of the local genre, and his writing has won coveted international prizes like the German Krimi Award (for Blood Safari); the Martin Beck Swedish Academy of Crime Writers Award (for The Golden Crowbar); as well as France’s Prix Mystère de la Critique (for Dead at Daybreak) and Littérature Policière (for Dead Before Dying).

“I love Deon Meyer. He’s like a mensch,” says Margie Orford, who’s billed by local media as the queen of South African crime thriller writers, and who already has four books published in nine languages. “There’s this warmth that comes from him personally that permeates through all his books. Deon captures this warmness about South Africans, even if they are not so cool, which makes them likeable. He has a straightforward directness. I also love the total confusion of his male characters in the face of the most simple, feminine wiles,” says Orford who says fuck a lot, speaks as fast as she does astutely, and doesn’t censor anything that comes out of her mouth. She’s all candour, which is fabulous, if you’re a journalist doing an interview with her.

Orford’s onto her fifth book, but says her fourth, Gallows Hill – which was launched late last year to critical acclaim – was almost the end of her. “Gallows Hill nearly fucken killed me. It was so hard. It was like blood from a stone. I was trying to write about slavery and apartheid, and that was very difficult conceptually, so I hit a total crisis of confidence, which I think worked. It’s always better to think that you are writing rubbish, because then you make it into something good,” she says.

The critics think Orford’s work is a lot more than “something good”. Columnist William Saunderson-Meyer says: “Orford is one of a select club of South African crime writers who have built an international reading audience. One can see why: she delights in perfectly rendered local colour and lingo, her characters are convincing, the setting – a police force in messy and sometimes dysfunctional transformation – is conveyed with unflinching honesty, and she writes with verve and a crackling energy.”

Offshore, the Daily Telegraph chose one of her books for its top five crime novels of 2011, while Jake Kerridge gushed of Daddy’s Girl: “Orford plots so brilliantly that to stop reading is as harrowing as to carry on.”

Like Meyer and many other brilliant crime novelists before her, Orford cut her teeth on journalism while she was still at the University of Cape Town, before working as a documentary filmmaker and investigative reporter. “When I came back to South Africa in 2001 I had been in New York on a Fulbright Scholarship. It just struck me how unbelievably violent South Africa was and I couldn’t work out why it was so violent. I started doing a lot of investigative stuff work then. I mean journalists are morons because essentially you just ask one question over and over again, which is why, why, why… why?” says the queen of crime.

“It seemed to me that the whole civil war of the 1980’s just sublimated into the body, into the family, and into intimate spaces. You know the rape epidemic, the extent of violence when there was a robbery or a murder, it was so excessive,” says Orford. To make sense of the violence Orford wrote for magazines and newspapers, but in many ways it felt like continually scratching the surface instead of mining deeper veins of meaning. “What I found with journalism is that there is a whole series of facts, but what you can’t really get at is the kind of truth that you have in South Africa which is ambiguous, complex and three dimensional. There is no right and wrong here, there is just a whole lot of complicated stuff.”

In fiction Orford believed she’d be able to move beyond the shallow two dimensionality of news reporting into a more multi-dimensional narrative arena. “I did a lot of sexual stuff like prostitution, trafficking, the drug trade, and how it was all kind of linked,” she says. Orford remembers interviewing a young prostitute on Cape Town’s Main Road near Kenilworth one day. I talked to this girl on the street in Kenilworth and asked her: “When are you at your busiest?” And she said to me: “Ag, half past seven.” So I said in the evening, but she replied no, that it was in the morning.”

Critics and crime enthusiasts love Orford’s realism, and perhaps it is because she sweats the details. “What is important for me is to create as closely as possible the milieu and the detail of what people do and how they interact. The challenge to me is not to create what my version of what a cop or criminal would be, but to actually write how I see them acting and behaving in relation to each other. I think you have to be very clever to make things up. I am just not clever enough. I have to go out into the world and see what’s there, and record that.”

Orford’s clever enough to be self-effacing. No one likes an arrogant ass, particularly in a literary genre that has very little snob appeal. The intellectuals ingest Vladislavi?-esque so that they can postmodern this, pre-modern that and wax eloquently about “anachronistic dilemmas” or exquisite symmetry. Orford’s form is tight and compact, and although she consciously never set out to write in the “krimi” genre it answered her perpetual why’s about rape, gang violence, aggravated assault and the battery of other depravities that make up everyday living in South Africa.

“There are writers that follow a formula of crime writing to offer their readers a repeat of that formulation. I didn’t think: ‘Oh my God I am going to write a crime novel.’ I was looking at South Africa and trying to make sense of it. I wanted to find out why things had gone so right in terms of politics, but so wrong in terms of our social interactions with people, and with this massive amount of crime,” says Orford. That’s when the crime writer realised that a 2,000 word article would never be able to begin to answer the question “why”. Orford needed a 100,000 word book, or series of novels to begin to answer the questions she had about this country.

But back to the young prostitute in Main Street, Kenilworth, Cape Town. The call girl told Orford that after the fathers had dropped off their kids at a private school in that plush suburb, they would see her before heading off to work. “I thought this is where the visible world of privilege with that moral impunity that people think they have, intersects with this other world from Belhar. Those two worlds intersect in that very intimate sexual act, and it was like a little writer’s window had opened for me,” says Orford.

Orford writes about that intimate space – where men and women meet in love or violence or hatred – pretty often. Her book Like Clockwork focuses on porn, prostitution and rape; while Daddy’s Girl deals with the abduction of little girls. Then there’s Gallows Hill which has a dead female body at the centre of the drama: “The woman lay curled up inside the small box. She had been jammed into it. Her head must have pressed up against the top, her feet against the bottom. Her belly would have pressed painfully against her lungs, her thighs. If she had been alive to feel it.”

“There is something majorly fucked up about how men and women relate to each other,” says Orford. “What’s interesting about sexual crime is that you have an intimate and personal expression about one person’s need for dominance and power over another person’s. I think that what has happened in South Africa is that masculine licence you had under apartheid – that very dominating alpha male thing that was lauded – is still being perpetuated. That aggression, that army-township conflict that we had in the eighties, to me it has just sublimated and went into the body. I think we had a civil war that was negotiated to a conclusion, but the anger and rage was still there in people.”

Orford never set out to wave a flag for sex power crimes, but says rather that the lesion of gender damage is just so prevalent and far-reaching in our society, that it’s impossible to escape. “If a mother has been beaten up, assaulted, or raped, her ability to relate to her sons and her daughters is severely compromised. It creates this social toxin. It is an interesting way of writing about power and the distortion of power. And then I have this annoying heroine, it bothers her so she is always investigating it.”

What’s common to all Orford novels is the “annoying” investigative profiler, Dr Clare Hart. She who’s in love with Captain Riedwaan Faizal of the South African Police Service’s elite gang unit; she who has a haunted familial past and who keeps a choked stranglehold on her emotions so that they’re hidden well away from view. There’s complexity in the relationship between Hart and Faizal, just as there’s a growing intricacy to Orford’s plotlines which in Gallows Hill deals with corruption, destructive jealousy, political antagonisms and factional interests that want the truth hidden at all costs.

Hart is Orford’s vehicle for journeying violence, for trying to understand South Africa’s innate viciousness, or more simply put, why we’ve been trying to murder each other and doing that very successfully at times, for the past 300 years. “It’s sociology for idiots, but this country has extreme patriarchal structures. We have had such a long and enduring attack on the family and intimate relationships between people,” says Orford.

This sustained and repetitious historical onslaught has come in the form of the Group Areas Act, the massive destruction of black family life, the creation of homelands or “Bantustans”; forced removals and more petty apartheid. “South Africa experienced the wilful political destruction of that family space and created what I have called a hyper masculinity. White people had children going into the army, and the guilt that comes from being a soldier fighting an immoral war. Those things we know, those things we can see. What I wanted to find out, and understand, is how this works in the day to day living of people’s lives.”

A pivotal moment in Orford’s life, which informed her thinking and writing, was the year-long creative writing workshop she ran for a group of maximum security prisoners at Drakenstein Correctional Centre, which at the time was called Victor Verster prison. “There were several of them who had no chance of parole; most of them were numbers gangsters – the kind of nightmare you pray is not waiting for you when you come home at night. But in many ways it was a soul altering experience for me,” says Orford, who adds: “If you want to smell despair, go to a male prison.”

Orford worked with the 15 prisoners whom she says carried their pain close to their skin. “It was like all this pain was so on the surface of them, and so unarticulated and unresolved. It was quite hard to work with them even though they wanted to do their stuff and concentrate. Who they were, what they had done and their life experiences were not at all integrated,” she says.

According to Orford, writing is a punishingly exacting verb. To learn to write creatively requires empathy and an ability to imagine yourself outside of your present situation.

“At the end of the year I had piles of handwritten stories and poetry on my desk,” Orford writes of her maximum-security creative class. In a self-penned article she headlined: “Working with these men helped me understand why South Africa is so violent”.

“The paper carries with it the unique smell of the prison: a dusty grey hopelessness of lives turned to ash. It turns the stomach, but working with these men has helped me understand why South Africa is so violent. It also taught me to find a connection between those we discard through fear, through revulsion at what they have done, the families they have shattered, the violence they perpetrate. The only path open to many township boys is so hard, so brutal that it annihilates the young and vulnerable self, the “bud” self, if I can call it that, that desires community, family and love.”

Orford ends the article with a poem that the oldest man in the class, Rashied Wewers, wrote her as a farewell note:

“I am

A book with a damaged cover, but what is

Written between the lines could save a country

From a disaster.”

“I used to go there and I would get a radical migraine as I finished. It felt like a sledgehammer had hit me. It would stay until just before I had to start getting ready for the next class, and I tried to work out why these migraines were so bad and so specific. I eventually worked out that I couldn’t hold the humanity of them in my head. How we were much the same,” she says then stating the obvious. The dissonance is of course what those men had done. “My brain, my heart – I don’t think we have a way of holding these two things together,” she says of the vast distance between the person and the deed. “What’s interesting is that you get people who behave extremely violently, and yet there’s a humanity about them. It just split my brain down the middle.”

Orford says that under “normal” circumstances there’d be no way she’d be having “conversations” with men “like that” unless they were hijacking her car or breaking into her house. “It was interesting, having this years’ worth (of conversations) and realising how much sameness there is, and also the utter stupidity of people who say apartheid was 20 years ago, stop blaming it. There is something about childhood and powerful socio-economic experience that creates how your synapses work, I think.”

Orford has now written four books back-to-back, to get what she says is “some sort of comprehension about South Africa – how it all fits together. The first book I wrote was horrible guys attacking nice, innocent girls. In Blood Rose I thought it was the army that fucked up everything.” The crime queen moves deeper into systemic violence with Daddy’s Girl where she looks at what a good man will do when he’s put under extreme pressure in a country that values bad, duplicitous men. With Gallows Hill she’s gone one step further by looking at South Africa’s “forgotten violence” – the slavery roots that set the bedrock for all our social interactions. “Socially we’ve forgotten that slavery was one of our original sins that haven’t been dealt with yet,” she says.

Despite her emerging success, SA’s first lady of local murderous lit is somewhat incredulous about the fame. “Writing’s good for mad people. It is quite a schizophrenic life because you are so in your head, and then you are so out in public. And then you are so in your head and so out in public. I used to have this nightmare when I was small that I would go to school without my ‘broekies’ on, or with my yellow, frilly, spotty pyjama ‘broeks’ which I managed to do once. It is like that feeling, like you’ll get caught out. But once I am over that hump I am fine.”

Frigging smart woman – and a hell of a lot more than just fine, I’d say. DM

Read more:

- Crime Beat: The year ahead for local crime fiction at BooksLive.

- Beyond That Lady Detective: African Crime Fiction in Publisher’s Weekly.

- Gallows Hill book review by Sue Grant-Marshall in Business Day.

- Find Margie Orford online.

- A life in writing: Henning Mankell in the Guardian.

Photo: Margie Orford and her novel Gallow Hills.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider