Media

The myth of the impartial reader blows up in SA as loud as anywhere else

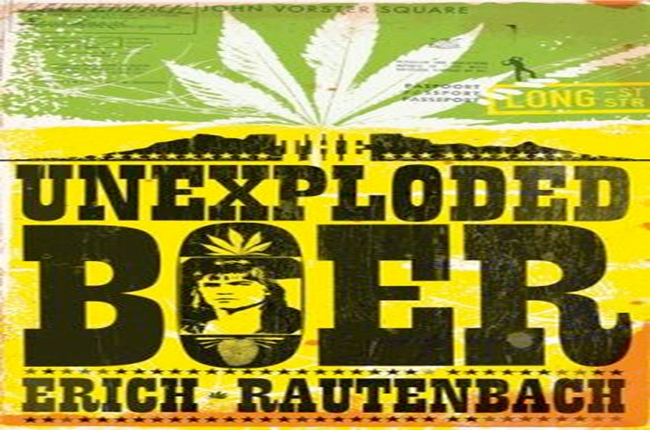

RUSTUM KOZAIN takes the measure of Erich Rautenbach’s dagga-infused novel – The Unexploded Boer – and finds in it an instance of the white guy trying to have his political cake, and eating it.

Attractive, young and a carefree rocker in 1970s Cape Town, Erich Rautenbach has one aim: to get out of South Africa before conscription to the SADF catches up with him. Driven by the root impulse that killing people is wrong, he has already ignored several call-up notices. But he is not from a family of means. To pay for his emigration he decides to deal in marijuana. He finds his way to Durban, the source of ‘Durban Poison’, intending to sell the marijuana in Cape Town. On a detour via Johannesburg, he is eager to sell some of the stuff, but ends up being set up by a friend’s brother and is arrested by undercover cops.

Opening with the arrest, this autobiographical tale covers about a year in the narrator’s life, from his arrest and detention at John Vorster Square, awaiting trail, to his eventual departure from South Africa. Somehow he manages to get himself transferred from John Vorster Square to Sterkfontein Sanatorium, from which he escapes, eventually making his way back to Cape Town where his mother helps him with a passage on board the Edinburgh Castle.

Interspersed throughout this main narrative is a range of digressions: his childhood in Cape Town, his life as a young man and drummer, his minor celebrity status and generally about his life as a rebel of sorts with little regard for petty apartheid. He plays with children from District Six and, later, when he has a job, disregards the segregation of toilets. There are also passages about politics and history and, late in the book, a touching section on boys who grow into men in the absence of fathers.

Suffused with a nostalgia for South Africa (following his departure in 1975, the author eventually made it to Canada, where he now resides), issues of belonging naturally pop up or hover in the background. Quite early on, the narrator presents himself as an outsider:

“Perhaps dislocation and not belonging has always been my fixed state or possibly it is the result of not being ‘branded’ into some society – circumcised, baptised, ritualised, confirmed, bar mitzvah’d, tattooed or otherwise inducted. Perhaps being the ‘outsider’ is just a twisted yearning to belong, a failed ‘member’ reconfiguring the thwarted hard-wired need to belong to a more complex social group.” (p. 29)

This provides heft to the rebellious persona who shows no regard for petty apartheid and who will evade the draft based on some felt sense of right. But it seems also a discursive tic by which the narrator hedges his ethical bets.

A common trope in post-apartheid autobiography is the need to position the narrator-writer in relation to apartheid. Most commonly, and most agreeably of course, is a positioning against apartheid. The narrator in The Unexploded Boer is at pains to show the extent to which he has drifted from the purview of white society.

Already mentioned is his disregard of separate amenities at his workplace and his childhood friends of District Six. But he also narrates other stories which show him in easy, familiar communion with ‘coloured’ characters in Bo-Kaap. However, as if wary of the trap of the post-apartheid trope, of being seen to be too eager to present his post-apartheid credentials, the narrator gives us the homespun wisdom on outsider-hood: the narrator is, if not born one, then an outsider, a rebel, by virtue of the absence of ‘proper’ early socialisation. He is, in other words, not positioning himself as an anti-apartheid rebel, because he has just always been a rebel.

There is a tension between how things are, on the one hand and how things may seem on the other. But the author has other ways of firming up his credentials, without seeming to firm them up. Out on a walk in the city one day, his young female companion is enthused by his popularity. She says to him: “It’s like you belong to them.” His response is to laugh, “out loud at the romanticism of the idea but [he] secretly hoped that she was right” (p39). He’ll give us this encomium of himself, but also disclaim it. Yet, he secretly yearns for it. And he can have it, although cleverly veiled by the disclaimer (“the romanticism of the idea”).

This two-step eventually adds a false note to the telling of the story, not because I doubt the facts, but because it marks an ambiguity in the story. The writer must or wants to present a certain profile, but appears all-too aware that presenting that profile might come across as too eager.

The use of slang is a mark of such eagerness. One can imagine the power that a country’s slang will have, in the writing of a story, on a writer who has lived somewhere else for so long. Language that is idiosyncratic to a time and place has remarkable force of evocation, so in the act of writing about a past time, a distant place, slang can transport the writer and be an aid to writing and to the representation of that distant time and place. And then, together with it being an aid to the writing, slang and other linguistic idiosyncrasies help to constitute the audience, and readers can then identify more readily with the story.

South African slang in The Unexploded Boer also constructs the narrator’s belonging, allowing identification with the country and South African readers. But here the use of slang does not prevent the narrator and the writer from keeping secret a certain eagerness, more so because of errors in usage or in transcription in the glossary, errors which then, alas, amplify the false note. “Zol”, for instance, is not exclusively marijuana, but refers to any hand-rolled cigarette. In the phrase “jou ma se fok se moer”, “fok” should be an adjective: “jou ma se fokken moer”. “Entjie” refers to a cigarette in general and not only to the butt. “Goffel” is a derogatory term for someone, most commonly girls and women, whose hair isn’t straight and not simply for “black guys”. And so on. Then there is also “Kullid”, which the writer claims, in the glossary, is his own version of the “insulting word “coloured”. I’m not sure of the etymology of “kullid”, which obviously mimics the pronunciation of “coloured” in certain dialects. There’s a website with the domain “Kullid.co.za”, so the word has provenance beyond Rautenbach’s invention. All this undermines the profile of the young man as someone who once belonged and who had easy congress across the colour line.

Early in the book, the narrator is well aware of the play of history on language. Describing his “dark thoughts”, he ends: “Today you might say I suffered from anxiety or depression, but we did not possess those socially approved words back then”. The narrator and the author is self-aware and easily switches between the present storyteller and the past persona. One could say the rebel in the narrator is reclaiming words such as “hotnot” and “Kullid”, but as continuing contestation over words like “nigger” and “kaffir” suggests, as well as “coloured”, that would be too easy an argument. At the very least, one would hope that just as the narrator (and author) steps outside of his past persona when it comes to his dark thoughts, he would do it with words like “hotnot” and “Kullid” as well, words which, used in such easy familiarity sticks in the craw of this reader. Here the writer and author’s self-awareness falters.

The upshot is that these signposts of belonging end up undercutting the writer’s intention by introducing a false note to any such post-apartheid positioning.

But perhaps this is all part of a larger problem of writing. The narration occurs at a steady clip. Swathes of history and politics are not only breezed through, but commented on using homespun wisdom and an easy, but eventually formulaic, humour. Naturally there will be rehearsals of common places of South African history in autobiography, and one does not expect dour political economy from this genre. But consider a passage, late in the book, on the names of airports in Cape Town and Johannesburg when the narrator lands back home. We’re given brief histories of DF Malan (architect of apartheid) and Jan Smuts (traitorous English-lover), and then: “But still, old General Smuts got the big airport named after him, the one in Johannesburg, while Doctor Malan ended up with the stinky little airport in Cape Town. Poor old Malan” (p197). And then it segues into a discussion of one of the author’s names, Daniel, and his family’s distant connection to the Malans.

Perhaps the name of DF Malan airport sets the mind adrift. Given the jocular tone and the pace of the passage, however, the reader does not get the sense of a mind drifting. It comes across, rather, as one more opportunity for the narrator to position himself vis-à-vis apartheid by way of an easy irony. This kind of humour suffuses The Unexploded Boer; it is sometimes mildly witty, but mostly maddening because it’s somewhat predictable. That is, you can see it coming, but you laugh along, because the teller of the tale is so affable. It is sometimes self-deprecating, but then also always in that double move where the narrator makes his joke – and laughs it off. The narrator has some gift of the gab and the narration moves at pace. So the reader is seldom bored; but nor is the reader compelled to linger over a turn of phrase or a fresh insight about life in apartheid South Africa. DM

The Unexploded Boer by Erich Rautenbach, Zebra Press, 2011.

© Stellenbosch Literary Project (SLiP), Department of English, Stellenbosch University. For other literary reviews, reports, blogs, translation and events, see www.slipnet.co.za.

ALSO on SLIPNET:

- A new Gus Ferguson cartoon on the matter of melancholy.

- A ‘youngster’ has an argument with his liberal father about Athol Fugard’s 1970s play, Statements, after they watch a production of this theatrical relic in Cape Town in 2012.

- Dominique Botha’s poem, Roudig, continues to pull in waves of comment on SLiPnet.

Photo: Original cover – The Unexploded Boer.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider