The image from the video of US Marines urinating on the remains of Taliban fighters in Afghanistan comes into focus as I watch Anthony Akerman’s anguished play, Somewhere on the Border at Johannesburg’s Market Theatre. It was first performed in 1986, at the height of South Africa’s war in Angola and what was then South West Africa, against SWAPO, the ANC and Cuban army and air force units, while Akerman was in exile.

After its first performances, the apartheid government promptly banned it. Some things do change. Now it has become a set work in university theatre programmes, a new printed edition is about to be released, the play was revived at the Grahamstown Arts Festival in 2011, and it is now on stage in Johannesburg – with all its dehumanising, racially offensive, sexually brutal language intact.

Seeing this drama, we follow a group of young men called up for their national service training in the 1980s, and then on to their rendezvous with disaster “somewhere on the border”. But their training, like the Marines in Afghanistan, the Army reserve unit that ran Abu Ghraib Prison, indeed, like my own military training decades ago, besides the drills in how to dispatch opponents, surely also included at least some indoctrination into what not to do as a soldier. (My military experience came after the atrocities of My Lai had washed across the psyche of the US Army in Viet Nam and forced just such training.)

The late 20th century was supposed to be much more than just a span of years beyond the horrors of the siege of Magdeburg in the Thirty Year’s War, the chemical warfare experiments of Japan’s 731 Special Unit on Chinese POWs, the sacking of Jerusalem by crusader armies in 1099, the Katyn Massacre of Polish officers, and the Death March of Bataan - and so much more. And this list doesn’t even count events like the bombing of Dresden, the Armenian genocide during World War I, the Holocaust, or Hiroshima.

Compare the account of the conquest of Jerusalem wherein one knight says: “One of our knights, Letholdus by name, climbed on to the wall of the city. When he reached the top, all the defenders of the city quickly fled along the walls and through the city. Our men followed and pursued them, killing and hacking, as far as the temple of Solomon, and there, there was such a slaughter that our men were up to their ankles in the enemy's blood…”; with a soldier who testified about My Lai: “I walked up and saw these guys doing strange things…Setting fire to the hootches and huts and waiting for people to come out and then shooting them… going into the hootches and shooting them up…gathering people in groups and shooting them.” Looking through the lens of the Marines’ action in Afghanistan, even though it was only a handful of men who carried it out, maybe it is less than clear-cut how far we have actually come.

The sharp point of any inductee’s initial training is to break down civilian inhibitions, including that fundamental moral position - “thou shalt not kill” – and to turn violence into a quotidian task. Together with others, one learns to kill the enemy. And, along the way, the enemy becomes depersonalised and dehumanised to justify this new behaviour.

And one learns to do this automatically. Orders come from higher ranking, more senior people who reconcile the moral conundrums in asking one to kill, giving new life to George Patton’s injunction that “the object of war is not to die for your country, but to make the other bastard die for his”. Probably every military has pushed virile young men to draw upon their impulses towards sexual expression, channelling them towards physical belligerence –exemplified in the universal chant of trainee soldiers, “This is my rifle, this is my gun; one is for pleasure, the other for fun”. The trainees in Somewhere on the Border chant this sexually charged refrain on stage exactly as my unit did nearly a half a century earlier on another continent.

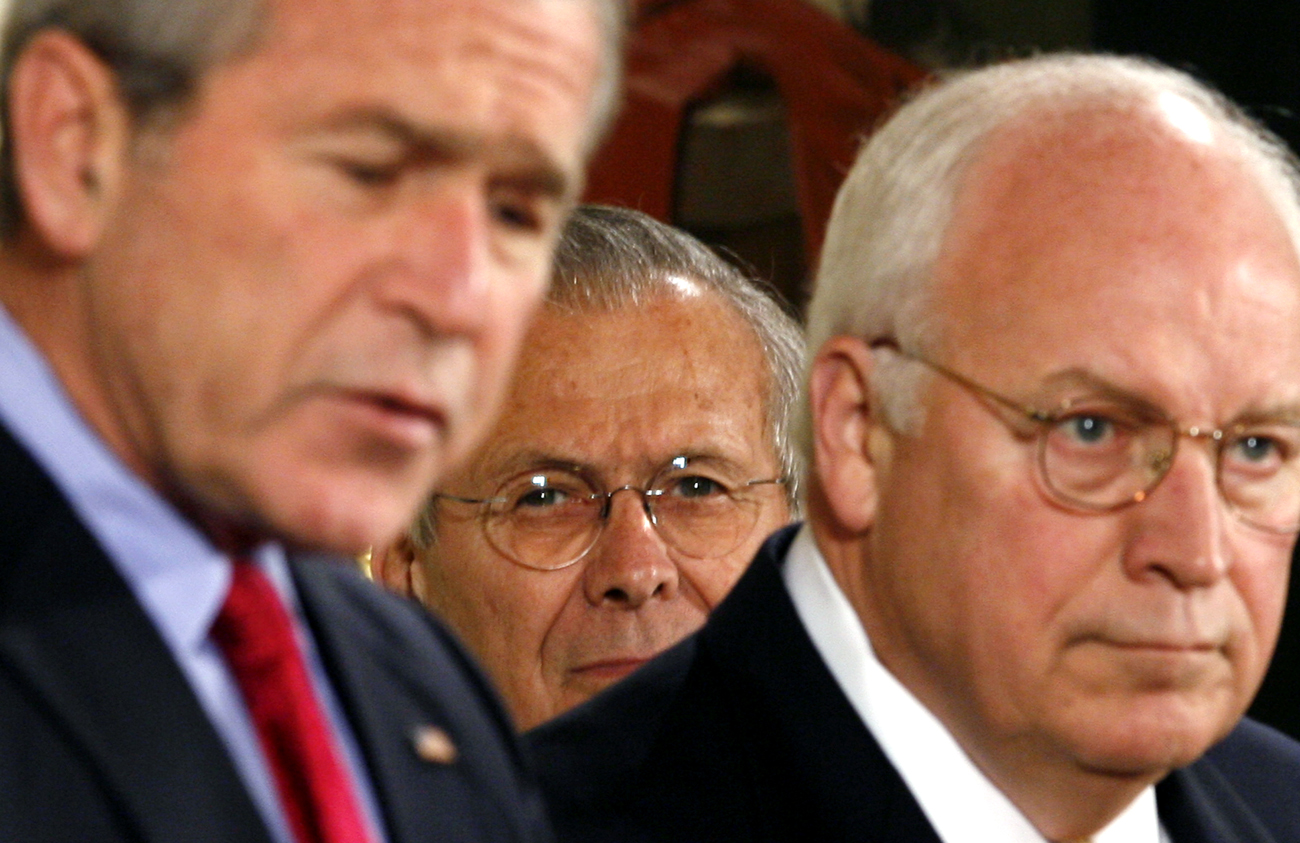

After learning of the Marines’ behaviour in Afghanistan with the corpses of their victims, President Barack Obama, secretary of state Hillary Clinton and defence secretary Leon Panetta were quick to call it “criminal”. No doubt they were thinking both about the act itself - and its implications for complicating even further US prosecution of the war in Afghanistan if it triggered protests or disturbances by the Afghan population against American troops. Significantly, perhaps, only Panetta had served in the military as an intelligence officer in the Army in the 1960s.

It being a presidential election year, Republican Texas governor Rick Perry, meanwhile, rose to the Marines’ defence, calling them “just kids” who had exuberantly misbehaved in victory over their opponents – sort of like a scouting trip that went a little awry. Perry had been in the military, albeit not in combat, but the warrior mentality clearly looms larger in his mind that in Obama’s.

Somewhere on the Border drags us into the moral quandaries of military life and gives us a window into the minds of troops everywhere - in Abu Ghraib or in Afghanistan. There is an element of nervous, off-tune fun in all of this until it turns into the real combat that demands choices about what one will do when it comes down to that final moral imperative. Or as Somewhere on the Border’s Doug Campbell, the man who preferred to chill on the beach with his friends, screams to no one and everyone, “I had no choice!” when he believes that he too must kill or be killed.

And so it is on to that other moral ambivalence of the military. Moral people must be recruited to serve, then broken and reshaped into soldiers – rather than selected from among those who would look forward to the killing in the first place. Such people must internalise what theologian Reinhold Niebuhr had described when he tried to give a moral basis for killing in the service of destroying evil, “There are historic situations in which refusal to defend the inheritance of a civilization, however imperfect, against tyranny and aggression may result in consequences even worse than war”.

Psychologist Stanley Milgram’s famous experiment in adhering to orders even when it causes pain and suffering is instructive here. In his experiment, students were asked to give (simulated) electric shocks to a presumed test subject so as to measure responses to pain. In truth the recipient of the shocks was an actor and the shocks were imaginary, but vivid. The real subject of the experiment was to observe whether people would continue to hurt others as long as they believed it was blessed (or at least acquiesced in) by authority figures.

Sadly, more than 90% of Milgram’s test subjects – who hadn’t even been subjected to military training or severe discipline - continued to apply simulated electric shocks until the actor behind the glass passed out from simulated pain. Interpreters of Milgram’s work felt it was experimental confirmation of “the banality of evil” so forcefully described by sociologist Hannah Arendt. Milgram’s experiment has become the watchword for how ordinary, normal people can be brought along to do extraordinarily horrible things to others with only a little encouragement. Not every soldier is a monster, and not every situation is right out of The Heart of Darkness obviously, but the process is one that lets those would become monsters move out from the shadows and do their worst.

Back during the Vietnam War, Arlo Guthrie, the counter-culture entertainer and pacifist, probably summed up the dilemma in his extended musical poem, Alice’s Restaurant. In the setup, Guthrie and friends dispose of their rubbish after a raucous Thanksgiving dinner in an old, deconsecrated church and, in the process, Guthrie receives a littering citation for dumping in the wrong place at the wrong time. This nearly invisible criminal record keeps him out of the military. “I said, ‘Shrink, I want to kill. I mean, I wanna, I wanna kill. Kill. I wanna, I wanna see, I wanna see blood and gore and guts and veins in my teeth. Eat dead burnt bodies. I mean kill, Kill, KILL, KILL.’ And I started jumpin up and down yelling, ‘KILL, KILL,’ and he started jumpin up and down with me and we was both jumping up and down yelling, ‘KILL, KILL.’ And the sargent came over, pinned a medal on me, sent me down the hall, said, ‘You're our boy.’ ”

Until Guthrie is confronted with his criminal record from littering, saying, “When I finally came to see the last man, I walked in, walked in sat down after a whole big thing there, and I walked up and said, ‘What do you want?’ He said, ‘Kid, we only got one question. Have you ever been arrested?’

“…Sargeant, you got a lot a damn gall to ask me if I've rehabilitated myself… ‘cause you want to know if I'm moral enough join the army, burn women, kids, houses and villages after bein' a litterbug….’ ’’ DM

Read more:

- “Stanley Milgram’s Obedience to Authority Experiments: Towards an Understanding of their Relevance in Explaining Aspects of the Nazi Holocaust” (Nestar Russell’s Ph.D., Victoria University, Wellington, NZ)

- US Marine Corps Soul Searching After 'Urinating' Video at ABC News;

- “Alice's Restaurant” the full text by Arlo Guthrie;

- 4 Marines in Video With Dead Taliban Are Identified in The New York Times;

- Video Inflames a Delicate Moment for U.S. in Afghanistan in The New York Times.

Photo: Reuters.