Media

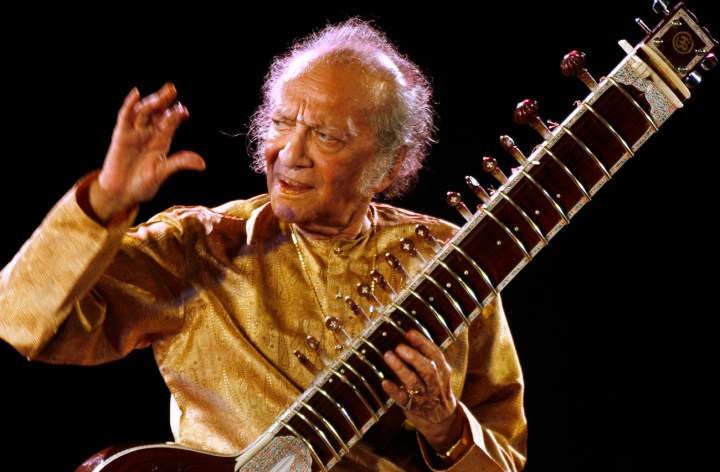

The Pandit enters his 10th decade: Ravi Shankar at 90

There are many astonishing moments in the life of sitar master, Ravi Shankar, which entered its 10th decade on 8 April. But this would merely be leaving grubby fingerprints on the giant edifice of a career that has skirted, and often bridged, two cultures. By RICHARD POPLAK.

We could mention his losing the best soundtrack Oscar he composed for Richard Attenborough’s “Gandhi” to John Williams for “E.T.” We could touch on his 40 years of friendship with George Harrison, which saw them win a Grammy together for their “Concert for Bangladesh” live album. We could allude to his relationship with concert producer Sue Jones, and the fruit of that union, superstar singer Norah Jones. But for those who have any hope of understanding Ravi Shankar, known to fans and followers as the Pandit, and his relationship to both Eastern and Western music, it is important to come to terms with the paradoxes built into his musical style. He is a meticulously trained traditionalist who was a modernising force in Indian classical music. He brought a Western sensibility to Eastern music and an Eastern mentality to Western music. He came of age in a unique time, and will not leave the world, culturally speaking, as he found it. Ravi Shankar changed everything.

He was born in 1921, in the holy city of Benares, into a cultured Brahmin family. When he was 10 years old, he was sent to Paris to train as a dancer for his brother Uday. Three years later, he was touring the West as a member of an Indian troupe. Most Westerners think of Indian music coming to the West in the 60s, which is only partly true: There was an appetite, in the 30s, for the sort of exoticism that Uday’s troupe trafficked in. Shankar learned French, grooved to jazz, watched Hollywood movies and by the time World War II broke out, was a thoroughly cosmopolitan young man—a hybrid cultural creature that understood both worlds, and more importantly, was of both worlds.

Watch: Ravi Shankar on the Dick Cavett Show

On his return to India, Shankar studied sitar under the master Allaudin Khan, in the temple city of Maihar. The training process was rigorous; he learned the modal ragas, the dhrupad, the dhamar and khyal. His education was full and deep, but there was other music pulling at him. Directly after his training, he moved to Mumbai and composed for two ballets in 1945 and 1946. But change was coming to India; the country was about to be cleaved in two, culturally riven. His work at the Indian National Orchestra acknowledged this fact—the compositions were hybrid works, a dazzling bridge between classical modes that suggested a richness and cultural empathy missing from even the most sophisticated music of the time.

In 1952 Shankar was introduced to the violinist Yehudi Menuhin and perhaps the most important musical relationship of his life began. Menuhin, more than any one man, was the conduit between Shankar and Western cultural tastemakers. Shankar’s first Western recording, “Three Ragas”, was a hit, if not a mainstream one. Indian music was played in concert halls and found its way into modernist recordings. The Indian modal style was particularly attractive to the modernist; it suggested ur-music, the tincture of music.

As happening as things were in the West, back in India, in the bloom of post-independence, Indian classical music was undergoing a golden age. There were the senior musicians, the established younger musicians like Shankar, an entire caste of students and sophisticated rasikas, or listeners, to whom Indian culture was intimately linked to the past. Over the subsequent decades, the scene curdled, the sound of classical sitar drowned out by the sitar setting on tinny synthesizers, which in turn become insufferable Bollywood soundtracks.

Watch: George Harrison & Ravi Shankar

The sixties, unlike any period in Western or Eastern culture since, was an open cultural frequency. Movements and ideas were traded with a rapidity and sincerity that challenges even the broader, but shallower Internet era. And Shankar was a vital element in this exchange. He never did play with The Beatles; legend gets this wrong, or, at least, partly wrong. After David Crosby of the Byrds introduced George Harrison to sitar music, Harrison’s interest in Indian music was further stirred on the set of “Help!”, which used some sitar movements in the soundtrack. He met Shankar in London in 1966, went to India, studied the sitar, used it on Rubber Soul’s “Norwegian Wood” thus introducing Indian music into mainstream Western culture.

Indian music’s signature moment in the West came from the “Concert for Bangladesh”—two shows in New York City’s Madison Square Gardens that Shankar and Harrison organised in aid of refugees from the Bangladeshi independence war. Dylan played, a rarity in the seventies, as did just-off-the-smack Eric Clapton. As with most cultural movements, its birth contained all the kernels of its death. The concert’s proceeds never made it to the refugees due to tax wrangling, and the do-gooder, Eastern ethos that Harrison introduced into 60s culture became infected with cynicism, so much so it was hard to take seriously by the mid-seventies. Harrison’s third solo effort, “Dark Horse” (1974) was dismissed for being too Indian, an orgy of sitar-ish swirls and ohm-type flourishes. When the hippy died off—or went to work for Goldman Sachs—so too did the Western flirtation with Eastern-ism and the means of listening, the act of being a rasika, that Shankar offered to a culture that desperately needed a way of encountering the world differently. Shankar himself took pains to distance himself from the hippy movement he’d inadvertently helped jumpstart.

Photo: Indian sitar player Ravi Shankar performs with daughter Anoushka Shankar in the eastern Indian city of Kolkata February 7, 2009. REUTERS/Jayanta Shaw.

For two decades The Pandit was intimately involved in two critical, and paradoxically oppositional, cultural movements—Western counterculture, and Indian traditionalism. As the West turned its back on hippy culture, so too a nascent India forgot the past, as any new nation must. India, of course, wasn’t new in cultural terms. But it had never experienced anything close to the wrenching of Partition and the political maelstroms of democracy that followed 1949. By the 80s, India had changed so irrevocably there was little space for Indian classical music. There were no state-of-the-art auditoriums in which to hear the masters play, no music schools to speak, and no state support for the old ways. In the 90s, as India underwent the growth spurts leading to its current economic superstar status, traditional music became even less necessary. It was either the trappings of the West, or flashy Bollywood bling culture, for the growing parvenu caste. In his dotage, the great Ravi Shankar looked up from his sitar, and realised the unthinkable had happened. The old masters had become anachronisms in a country that had no interest in its traditions.

Watch: Norah Jones, Don’t Know Why

The ragas will, of course, outlast all of this cultural back-and-forth, they’ll outlast Shankar and they’ll outlast his students’ students. They’re deathless, and contain elements as old as humanity itself—an essential rhythm that is instantly recognisable to anyone who hears it. Ravi Shankar’s ultimate gift to the two cultures he straddled so effortlessly, and with so much effort, was to play this music at such an exceptionally high level, and with such empathy and genius, that he has further tattooed it on our collective cultural memory, ensuring its immortality.

He is 91 now and the music is often drowned out by the clutter of his extraordinary life. “The only way you can impress is with your music,” the Pandit has said. Impress us, he did. DM

Read more:

- Ravi Shankar’s official website;

- The East meets West label website.

Main photo: Indian sitar player Ravi Shankar performs in the eastern Indian city of Kolkata February 7, 2009. REUTERS/Jayanta Shaw.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider