The agonies at Japan’s Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear reactors have become a movie that almost certainly is only going to get worse. Hour by hour, nobody has been able to come into the briefing room to say, "We are happy and grateful to announce we have brought things under control at the damaged reactors - the containment vessels are secure, the cores are being damped, the radiation is thoroughly contained and the coolant temperatures continue to fall." And it appears that it will not happen for a long time.

As the Christian Science Monitor explained on Wednesday:

“Workers at Japan's stricken Fukushima nuclear power plant are still days – if not weeks – away from bringing the crisis under control. The reason: nuclear fuel rods remain dangerously hot well after reactors are shut down, and all cooling systems at Fukushima have failed.

“Emergency workers are still struggling to contain a crisis at a Japanese nuclear plant five days after an earthquake and tsunami pulverized Japan’s north-eastern coast. Yet the reactors at the site shut down automatically when rocked by the quake 11 March. Spent-fuel pools contain fuel rods removed from reactors months ago.

“Why is it taking so long for all this fissile material at the Fukushima Dai-ichi complex to cool down? The answer to that question is that, without artificial cooling, nuclear power-plant fuel remains ‘alive’ enough to generate combustion-level amounts of heat and dangerous radioactivity for months on end. And at Fukushima, the earthquake and tsunami have knocked out these crucial artificial cooling systems.”

Bureaucrats and officials, rather than comprehensive briefings, have engaged in the fragmentary release of incremental bits of information about the continued leakage of radioactive steam, potentially ruptured containment vessels, fires in spent nuclear fuel storage areas, updates on some heroic struggles of beleaguered technical crews rigging ad hoc arrangements to bring raw salt water in as a last-ditch effort and dark mutterings about what occurs when a core meltdown actually happens - or worsens.

For example, one government official from Japan's nuclear regulatory agency said while flames and smoke were no longer visible at the site, he could not clarify if the fire at Reactor 4 was out. Similarly, he could not confirm if there was a new fire or whether it was still the fire from Tuesday. All of this has underscored the company’s problems in bringing the plant under control and this confusion exemplifies a record of often-contradictory reports about what is happening at the plant.

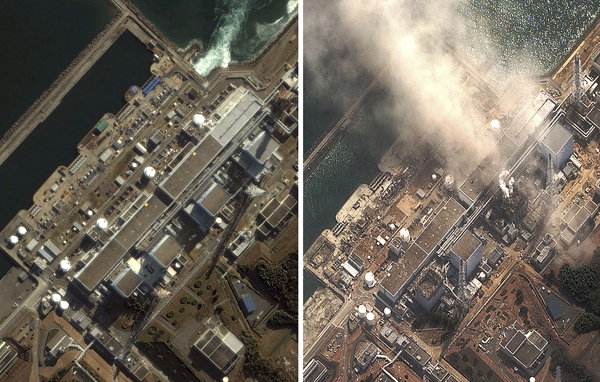

Photo: A combination of handout satellite images show the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant on November 21, 2004 (L) and on March 14, 2011 (R) as the No.3 nuclear reactor is burning after a blast following an earthquake and tsunami. The Fukushima nuclear complex, 240 km (150 miles) north of Tokyo, has already seen explosions at two of its reactors on Saturday (reactor No.1) and on Monday (reactor No.3), which sent a huge plume of smoke billowing above the plant, just days after a devastating earthquake and tsunami that killed at least 10,000 people. REUTERS/Digital Globe

Thanks to the combination of Japan’s historical nuclear experience and the impact of 24/7 international satellite news, for people actually living beyond the immediate reach of the damage, this nuclear drama is becoming all-consuming. And Japan’s nuclear agony is fuelling a growing worldwide debate about the future of nuclear power. As The New York Times summarised on Wednesday: “On March 11, 2011, an earthquake struck off the coast of Japan, churning up a devastating tsunami that swept over cities and farmland in the northern part of the country and set off warnings as far away the west coast of the US and South America. Recorded at 8.9 on the Richter scale, it was the most powerful quake ever to hit the country. In the days that followed death estimates soared astronomically, with officials saying that more than 10,000 had died in one seaside town alone.

“As the nation struggled with a rescue effort, it also faced the worst nuclear emergency since Chernobyl; explosions and leaks of radioactive gas took place in three reactors at the Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Station that suffered partial meltdowns, while spent fuel rods at another reactor overheated and caught fire, releasing radioactive material directly into the atmosphere, and spent fuel rods at two other reactors showed increasing temperatures.”

The Fukushima Dai-Ichi plant - actually a series of separate reactors operated in parallel to generate electricity for Japan's national power grid – contained six of the country’s 53 nuclear reactors that generated about a third of the country’s electricity. The Dai-ichi reactors are located on the Pacific coast in the largely rural prefecture of Fukushima north of Tokyo.

More than most parts of the country, Fukushima and much of the rest of the Tohoku, at least sometimes, still move to older, time-honoured patterns and rhythms. The fertile valleys (fed by aeons of volcanic pyroclastic flows) still have something of the look of Japan before the country’s industrialisation set in – if you can just avoid seeing the high-tech factories and high-speed rail lines. Here and there, even a few old-style thatch farmhouses set back from the roads and craft traditions still thrive in many parts of the Tohoku. In winter, the snow-covered vistas look even more like something out of a traditional Japanese woodblock print. Fishing villages along the coast have often remained smaller rather than the sprawling extensions of larger towns.

The region has its great historic tales that somehow seem closer to people in that region than their equivalents in other parts of Japan. One of the last battles fought by the Shogun’s samurai against the new imperial army took place near the Aizu River in Fukushima. Sendai has its samurai hero, Date Masamune, and the northern reaches of the Tohoku remembers an heroic, even foolhardy, winter march through mountain passes by a detachment of the Japanese army on a training mission that inspired the country’s military for decades – a fanatical devotion to carrying out orders that akin to Thermopylae - only without the Persians.

Photo: People watch a television broadcasting Japan's Emperor Akihito's televised address to the nation at an electronics retail store in Tokyo March 16, 2011. Japanese Emperor Akihito said on Wednesday problems at Japan's nuclear-power reactors were unpredictable and he was "deeply worried" following an earthquake he described as "unprecedented in scale". It was an extraordinarily rare appearance by the emperor and his first public comments since last week's devastating earthquake and tsunami that killed thousands of people. REUTERS/Issei Kato.

The Tohuku is also a summer vacation spot for many more urban Japanese. They take in the historic spots, the natural beauty of the region, the really wonderful “onsen” - traditional inns with relaxing, rejuvenating hot springs. But most of all they come to the region’s cities because of some great summer festivals that reach back to ancient rituals probably predating the introduction of Buddhism – imagine a Britain whose towns still celebrate the Roman Saturnalia or even some earlier Celtic solstice ritual in place of Christmas. Thousands and thousands of otherwise worldly 21st century Japanese join in a great carrying of floats and night illuminations through the streets of cities like Sendai, Morioka, Akita, and Aomori, along with some heavy-duty eating and drinking.

Along the coast from Sendai is Matsushima Bay, a spot famous for some 260 tiny islands covered in pines - a vista ranked as one of Japan's traditional “Three Great Views”. In 1689 Japanese haiku poet Matsuo Basho visited there in his book, the “Narrow Road to the Deep North”. Basho is said to have proclaimed Matsushima’s beauty in his poem that implied it was such a beautiful spot that it was beyond words, hence his poem: “Matsushima ah!/A-ah, Matsushima, ah!/ Matsushima, ah!” (Trust me, it reads better in Japanese.)

But all of that is going to be overwritten by the new emerging storylines of earthquake, flood and nuclear generator fire. A look at the pictures of the appalling damage to coastal towns and cities with their blasted neighbourhoods with middens of rubble and splintered timber where houses used to be is to call to mind the pictures of Hiroshima and Nagasaki after the atom bombs. And the story for this new devastation is going to keep on moving as the reactors continue to be a danger.

By Wednesday evening, some nuclear experts, after examining the problems at Dai-ichi, have been saying ominously the reactor problems are effectively out of control – comments that immediately had negative effects on the stock exchanges still open for business at that time. Then, late on Wednesday night, the head of the US nuclear regulatory commission, Gregory Jaczko, said the damage at one of the Dai-ichi reactors was much worse than Japanese officials had acknowledged and advised Americans to evacuate a wider area of 80km, around the wounded plant rather than the 20km evacuation perimeter established by Japanese authorities. Brace yourself for worse in the days to come.

In fact, the combined issues have been severe enough that in a virtually unprecedented event, compared to his usual carefully scripted, anodyne remarks, Emperor Akihito went on national television to reassure the nation that everything that can be done was being done. But also to call the calamities something unprecedented for his country since World War II. He urged the nation to persevere and “to never abandon hope” in words that echoed his father’s (pre-recorded) radio speech on 15 August 1945 when he told the nation to “endure the unendurable” - surrendering unconditionally to the Allies.

Photo: Evacuees, who fled from the vicinity of Fukushima nuclear power plant, rest at an evacuation center set in a gymnasium in Kawamata, Fukushima Prefecture in northern Japan, March 14, 2011, after an earthquake and tsunami struck the area. REUTERS/Yuriko Nakao.

If this were an action movie, Steven Seagal, Bruce Willis, Harrison Ford and Arnold Schwarzenegger, partnered up with the ever-suffering Ken Takakura or a clever but smirking Ryuichi Sakamoto, would have led a band of hardy reactor workers who, at the last second, would connect the last hose left to flood the containment vessels with cold water, thereby preventing the destruction of Tokyo as the radioactive winds shifted south.

But Japan’s actual heroes so far have been virtually anonymous. While Tepco, the reactor operator, has pulled back much of its crew in the face of radiation dangers, about 50 so-far faceless engineers – down from a more usual complement of 800 - are working in what may be dangerous last-ditch efforts to bring the radioactive cores under control.

The New York Times described them as: “A small crew of technicians, braving radiation and fire, became the only people remaining at the Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Station on Tuesday - and perhaps Japan's last chance of preventing a broader nuclear catastrophe. They crawl through labyrinths of equipment in utter darkness pierced only by their flashlights, listening for periodic explosions as hydrogen gas escaping from crippled reactors ignites on contact with air.

“They breathe through uncomfortable respirators or carry heavy oxygen tanks on their backs. They wear white, full-body jumpsuits with snug-fitting hoods that provide scant protection from the invisible radiation sleeting through their bodies. They are the faceless 50, the unnamed operators who stayed behind. They have volunteered, or been assigned, to pump seawater on dangerously exposed nuclear fuel, already thought to be partly melting and spewing radioactive material, to prevent full meltdowns that could throw thousands of tons of radioactive dust high into the air and imperil millions of their compatriots.

“They struggled on Tuesday and Wednesday to keep hundreds of gallons of seawater a minute flowing through temporary fire pumps into the three stricken reactors…. The workers are being asked to make escalating - and perhaps existential - sacrifices that so far are being only implicitly acknowledged: Japan's health ministry said (on) Tuesday it was raising the legal limit on the amount of radiation to which each worker could be exposed, to 250millisieverts from 100millisieverts, five times the maximum exposure permitted for American nuclear plant workers.

These employees are becoming emblematic of Japan’s response to this disaster trifecta, representative of a people who routinely put group over self, who refuse to give up despite the impossible challenges and who work closely together with what sometimes seems like an instinctual sense for cooperation. One can almost hear their countrymen and women urging them on silently with calls of “O dai ji ni” and “Ganbatte!” - “Please take care of yourself” and “Keep it up, don’t give in.”

While it may seem callous to consider how the disasters will affect Japanese politics, analysts are already saying these events will be an existential challenge for Prime Minister Naoto Kan, just as it has become for staff at the reactor sites. Kan’s Democratic Party has been grimly hanging on to power after taking over from the Liberal Democratic Party that had ruled Japan almost continuously since the 1950s. Kan’s party, by contrast, has had a shaky existence with defections and resignations marking its rule since it came to power late in 2009. With the most recent resignation, that of his foreign minister Seiji Maehara, Kan’s tenure seemed destined for failure. Clearly at this time, if ever, Japan needs energetic, vigorous leadership, but its oblique system of governing may make this difficult.

In the past, there was a close relationship between regulators and the regulated, pre-eminently between energy regulators and power companies, and most especially with nuclear power. Eager to lower dependence on fossil fuels, the regulators steered the country towards nuclear power, despite deep distrust by the populace, stemming from its World War II experiences. Given deep scepticism in the media about nuclear power as well, the companies and regulators kept information close to their vests to avoid giving fuel to opponents that ranged across the spectrum from pacifists to environmentalists.

In fact, even until now, Tepco, and not the politicians, have been the ones to plan the blackouts and so far, there has been little warning or scheduling information (does that sound familiar?). And critics are already charging that rivalries between high-level bureaucrats and politicians from different ministries are making it harder to create a way to coordinate relief efforts and reassure the public. This contrasts with the publicly visible efforts by ordinary Japanese bureaucrats, engineers and citizens to cope with the devastation – television footage already shows people carting away the wreckage and clearing lanes for larger work despite what looks like a truly Sisyphean enterprise.

As I was trying to write this piece, my computer wireless network suddenly went haywire. As our computer specialist was working to restore order among the various electronic boxes, he asked me, “Given what has happened to Japan, where should one invest over the next two years?”

Interesting question, that. Of course, the Japanese will rebuild. And as companies begin to sort out their shutdowns and start back-ups to adjust to rolling blackouts, transport disruptions, workforce dispersals and the inability of suppliers to bring inputs in to larger firms, it may not be too soon to contemplate the impact of the crisis on the global economy. As with any other crisis, there will be winners and losers. While some companies will be unable to produce their usual products, the damage is so profound and the demand for materials for new infrastructure to replace what has been destroyed will be certain to grow nearly exponentially. If companies like some high-tech giants suffer because of the disruptions to their supply chains, suppliers of more prosaic items like ships, trains, electrical and water reticulation supplies, building materials, steel and concrete must already be preparing new order books.

And in fact, the Japanese government has been down this road before. The country’s great industrialisation a century-and-a-half earlier was kick-started by government licenses to produce materials for export to the rest of Asia, and for locally made materials for building railroads, harbours and armaments. In the great rebuilding after World War II, government contracts and the precise allocation of scarce raw materials again led the way to economic recovery.

Once the grieving is over, soon enough, the Japanese bureaucrats will be issuing a thoroughly developed blueprint for a national mobilisation to rebuild, to create environmentally friendly cities and for the creation of new technologies in recycled energy generation or new integrated transportation networks across the Tohoku region. You can bet the farm on this. And international markets may have already started making such wagers – The Financial Times has announced the yen has reached its highest level ever against the dollar. DM

For more, read:

- Japan -- Earthquake and Tsunami (2011) in the New York Times;

- Japan Says 2nd Reactor May Have Ruptured With Radioactive Release in New York Times;

- Last Defense at Troubled Reactors: 50 Japanese Workers in the New York Times;

- In Japan, No Time Yet for Grief in the New York Times;

- Radiation Thwarts Helicopter Plan in the Wall Street Journal;

- Meltdown 101: Why is Fukushima crisis still out of control? in the Christian Science Monitor;

- Flaws in Japan’s Leadership Deepen Sense of Crisis in the New York Times;

- U.S. Calls Radiation ‘Extremely High’ and Urges Deeper Caution in Japan in the New York Times;

- Yen hits record high against dollar in the Financial Times.

For readers who wish to make contributions to assist in recovery in Japan, the American School in Japan (a highly regarded, well-known educational institution that includes among its alumni actor Oliver Platt and Japanese pop music sensation Hikaru Utada) recommends the following websites:

- Donations to The Red Cross Japan;

- Donations to a group fund for NGOs working in disaster relief including Doctors Without Borders and Habitat for Humanity;

- Donations to the Red Cross fund for Japan; (Donations can also be made through iTunes)

- Donations to Doctor's Without Borders fund for Japan;

- Donations to NGO funds through Paypal;

- Donations through Global Giving;

- Donations to International Medical Corps;

Main photo: A rescue worker uses a two-way radio transceiver during heavy snowfall at a factory area devastated by an earthquake and tsunami in Sendai, northern Japan March 16, 2011. REUTERS/Kim Kyung-Hoon.