Politics

Book Review: What China is thinking, and what this means for Africa

Africa is obsessed with China. The People’s Republic casts an increasingly deep shadow across the continent – and in the half-light, Africans struggle to understand what the era of Chinese encroachment might mean politically, intellectually and economically. What Does China Think?, British think-tanker Mark Leonard’s slim 2008 book, takes a brief intellectual tour of modern China, and hints at what could be in store for Africa. Think of it as essential holiday reading. By RICHARD POPLAK.

Mark Leonard contends that we have ignored the intellectual impetus behind the Chinese economic miracle, mostly because we have no clue that there was one. When most Western pundits consider the Chinese rise, they see it as the realisation of an authoritarian economic mandate, helped along by China’s staggering demographics. What Does China Think? places the economic remaking of China in a different context: as a “powerhouse” of sometimes competing ideas that are not merely Chinese in nature, and may one day serve as a potent alternative to the waning export of neo-liberalism.

The West’s traditional lack of interest in Chinese ideas is embarrassing. There have been no contemporary Alexis de Toquevilles, travelling from hill to dale in an attempt to explain the intricacies of a new power to the old elite. Like the uninterested diner who orders a grilled cheese sandwich in a Chinatown restaurant, Western pundits have long assumed that Western ideas – much like Western products – would slowly infiltrate China as its economy opened up. That hasn’t been the case. Indeed, since the “cult of America” lost its lustre in the mid-90s, China’s (largely Western-trained) intellectuals have reconsidered the very notions of globalisation, soft-power and any number of op-ed approved buzzwords, and reframed them in Chinese terms.

Leonard introduces us to a coterie of boffins who form part of China’s vast think-tank community. Not all of these intellectuals make the grade, but the point is that the leadership is no longer the preserve of strong men who impose top-down programmes on a whim. The process of idea-generation in China is vibrant and collaborative, which doesn’t make it free and democratic. Indeed, Leonard says that China is “the most self-aware rising power in history”, constantly testing its precepts through PowerPoint presentations in Chongqing or Beijing convention halls. The Communist Party increasingly resembles a technocracy, a repository of sometimes bitterly contested ideas about the future of the world’s most populous nation, and the rest of the world along with it.

Mao’s successor Deng Xiaoping, who was largely responsible for the Chinese economic rise, dropped dozens of Big Brother-ish bon mots over the course of his quarter-or-so century as paramount leader. Arguably the most important was his description of local capitalism as “socialism with Chinese characteristics”. In 1992, standing in the middle of the Special Economic Zone in Shenzen – local capitalism’s ground zero – Deng is alleged to have told his people that, “to get rich is glorious”. Some would get wealthy while others remained poor; certain regions in China would be sacrificed in order to fuel the Pearl River Delta economic engine. No matter: this was brute capitalism, where everything in China was subject to stratospheric year-on-year growth.

It was the era of the Chinese economist, a cohort who had the ear of power, and – armed with degrees from Oxford, the London School of Economics and the Kennedy School – provided the intellectual scaffolding for rapid economic expansion. Led by the famous, controversial Zhang Weiying and the Shanghai Set, this “New Right” preached the values of neo-liberalism in the context of a small (but undemocratic) state, a sort of growth uber-alles system exemplified by so-called “dual-track pricing” – a means of weaning the economy off central planning, and into the free market.

Every generation in China molts an ideal. In opposition to Weiying and his acolytes stand an increasingly powerful “New Left”, who consider the divisions between China’s super-rich and ungodly poor as a potentially cataclysmic social fault line. They envision a statist model, with equality and political democracy “at the expense of total market freedom”. This doesn’t mean free elections and constitutional rights for all, but rather “social harmony” woven into safety nets, such as pension plans, health care and affordable education. The New Left now sits at the foot of power; President Hu Jintao’s bumper-sticker sayings read “Harmonious Society”, “Scientific Development” (code for stable growth) and yiren weiben – putting people first.

It may be self-preservation, it may be a result of genuine intellectual heavy-lifting, it may be a combination of the two. But few of China’s mainstream thinkers are advocating for Western-style blanket suffrage. Indeed, their solutions increasingly dismiss the notion of open economy married to an open political system. “What has emerged in the place of the liberal democracy that the West predicted is a more sophisticated variant of dictatorship,” writes Leonard. And while free market capitalism has ushered in experiments with direct representation, democracy as we have come to understand it looks more and more of a chimera in China every day.

What, one wonders, does this mean for Africa? Are these ideas – or anti-ideas – exportable? With the establishment of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation in 2002, and the opening of the Special Economic Zone in Chambishi, Zambia, in 2007, China has made it clear that it is in Africa to stay. It’s been criticised for offering soft loans to bad men; it is quietly applauded for investing billions in infrastructure. No one in the West, however, seems to quite understand what China’s larger intentions might be. Where Deng once said “hide brightness, nourish obscurity”, the 12th Five Year plan in 2012 will urge the People’s Republic to “go global”. China’s growth is now incumbent on the People’s Republic vociferousness and, in some cases, belligerence, on the international stage. The Neo-comm hawks rise, and they demand an interventionist China.

One thing is clear: it will be easier for China to deal with African nations that mirror its own model. Democracy is messy; transparency is a bitch. The idea of a network of nations with “walled” systems – which is to say, free market economies, but not free countries – would allow China and its African pals an unregulated, fast moving and very lucrative means of exchanging commodities for infrastructure and loans. Looked at this way, What Does China Think? can occasionally be read as What Does Africa Think?

Leonard’s book is limited in scope and approach: his intellectuals are insiders, and he underestimates the reach of dissidents – none of whom he speaks with – whose ideas percolate away on the Internet, influencing China’s increasingly restive young population. (Indeed, dissidence is a variable track in China, and sometimes a solid career move.) That said, it’s a starting point – a way of coming to terms with ideas that are bound to shape many African countries in the coming years, perhaps South Africa included. The lure of an all-powerful one-party state that steers an open economy, resists the flattening of globalisation and manages its social problems through “harmony” can look pretty sexy, depending on your point of view. But there are no beautiful ideas on display: no beacons on the hill, nothing transcendental. Just the grayish hue of brute pragmatism. One wonders if Africa can’t do better. DM

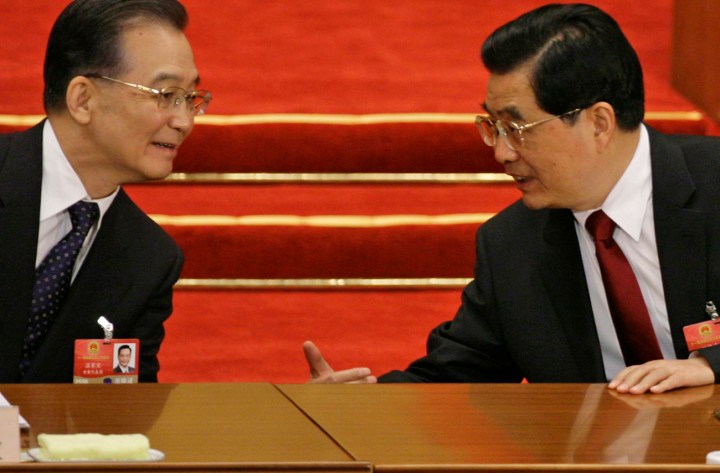

Main Photo: China’s President Hu Jintao talks with Premier Wen Jiabao (L) ahead of President of the Supreme People’s Court of China Wang Shengjun’s work report during the third plenary session of the National People’s Congress (NPC), in Beijing March 10, 2009. REUTERS/Jason Lee.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider