Africa, Business Maverick, Politics

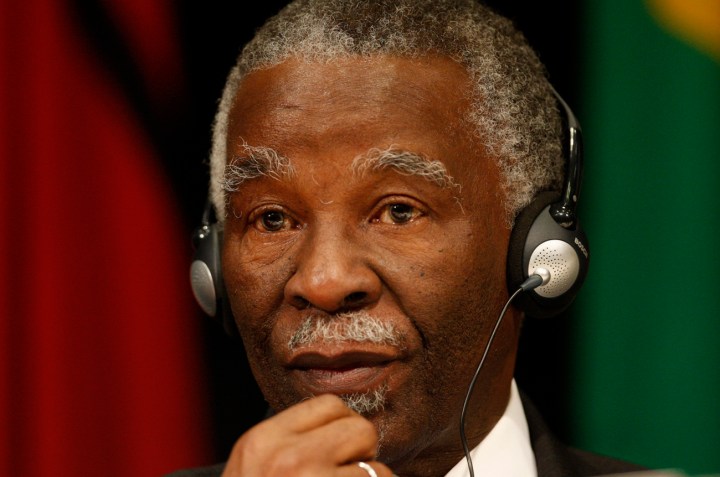

‘Foundation’ trouble: What Thabo Mbeki is up against

The Thabo Mbeki Foundation was launched on Sunday 10 October, with the stated aim of assisting Africans to reaffirm their dignity amongst the world’s nations. While charges of hypocrisy are bound to be leveled at Mbeki, the fact remains that even the most powerful foundations have their inconsistencies. Giving back is a complicated business. By KEVIN BLOOM.

It’s right there on the website: the second guiding principle of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is that “philanthropy plays an important but limited role.” Although the site doesn’t expand on the statement, a sense of what’s meant can be gleaned from some of the principles that follow – principle three, for instance, which states that “science and technology have great potential to change lives around the world”; or principle nine, with its mantra-like message that “we must be humble and mindful in our actions and words.” Maybe it’s because the foundation is the largest transparently operated institution of its kind in existence that these guiding principles, a little vague on first reading, take on universal significance. With an endowment of $33.5 billion, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is saying it isn’t all about the money.

But isn’t it? Between the mid-1990s and 2008, when Bill Gates resigned from an operational role at Microsoft to focus full-time on his charitable activities, his media profile underwent a metamorphosis; where before he was known as the wealthiest man in the world, a supremely gifted technophile given to ruthless and monopolistic business practices, now he had been reincarnated as one of the planet’s biggest givers. The fact that as of 2007 he had donated $28 billion of his own funds to charity certainly helped, as did his pioneering of a new type of charitable endeavour known as “philanthrocapitalism”. It’s been the money, always the money, that’s made the narrative of Bill Gates so compelling – how he’s accumulated it, how he’s given it away, and most importantly how much of it there is.

Again, there must be something in the sheer size and scale of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation that serves as an object lesson to other foundations throughout the world – if for no other reason than the funds at its disposable, irrespective of the intentions of its trustees, render it an archetype. And perhaps the greatest lesson it has to offer is this: the goal of redistributing wealth, power or resources to those “in need” is far more challenging and problematic than the goal of attaining such things in the first place. For every win, it seems, there’s going to be someone somewhere pointing to an equivalent loss.

Take the scholarships offered by the Gates Millennium Scholars fund to only African American, Native American, Asian, Pacific Islander American or Hispanic American applicants – an op-ed was published in the Los Angeles Times that argued the exclusion of Caucasians would “further inflame racial tensions, delay the achievement of a colourblind society and subvert the cherished virtue of reward by merit.” Or the foundation’s philosophy of continuously reinvesting the portion of its assets that have yet to be distributed (the “capitalism” part of philanthrocapitalism), which has included investment in companies accused of worsening poverty in the very countries where it’s trying to fight the scourge. Or the fact that the foundation’s payment of high salaries at Aids clinics has been consistently criticised for diverting medical professionals in developing countries away from areas where their expertise is equally (if not more) needed.

The complicated politics of giving are evident, in fact, amongst all top three of the world’s wealthiest foundations – and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, at number two, has by no means attracted the worst of the flak. Stichting INGKA Foundation, which at an endowment of $36 billion is the largest charitable institution in the world, differs from the Gates Foundation in that its records are not made public; in 2006 The Economist magazine alleged that Dutch company INGKA uses the foundation as a tax-avoidance scheme and anti-takeover vehicle for IKEA, its major asset. The Wellcome Trust, meanwhile, at number three on the list, was accused by the Indian government in August 2010 of a major conflict of interest – the non-governmental organisation, which funds biomedical research, was linked to a pharmaceutical company that had a lot to gain from announcing the discovery of a “superbug” in Indian hospitals.

Given the above, the trustees of the brand-new Thabo Mbeki Foundation would be naïve to think that such allegations – which are essentially allegations of “hypocrisy,” of saying one thing and doing another – are not going to be leveled at them. Launched on Sunday 10 October before African dignitaries that included former Ghanaian president John Kufuor and former Mozambican president Joaquim Chissano, the foundation’s aims are encapsulated in the following words of Mbeki: ” I can think of no more noble objective to pursue than the realisation of the aspirations of the peoples of Africa to rise from the ashes, to achieve their renaissance, to reaffirm their dignity among the nations, to depend on their native intelligence and labour to transform their dreams into reality, acting in unity as Africans.”

It is a noble objective, maybe even (as per Mbeki’s own thoughts) the most noble one out there, but what does it actually mean? The three-day conference that followed Sunday’s announcement provided some context. The Thabo Mbeki Foundation, it appears, is to be launched in tandem with the Thabo Mbeki African Leadership Institute (TMALI), and while the former will have as its goal the eradication of poverty and underdevelopment in Africa, the latter will attempt to train and provide the kind of leaders who can make the dream a reality.

An article appeared in the Sowetan newspaper on Thursday 14 October that summarised what was said at the conference: “As one of the speakers, Shingai Ngara from Shingara Integrated Investments, pointed out during the discussions, Africa has the sun, deserts and the wind. Why then do African countries not go full force in developing these as alternative sources of energy? By so doing they would develop their research capacity, develop skills and position themselves as key suppliers of alternative energy.” Further down, the article continued: “If indeed cost is an inhibiting factor, focusing on these initiatives will, for example, force the country to develop technologies that can eventually make the process cheaper. This will in turn develop the country’s technological capability.”

How can African mindsets be changed to the extent that this idea becomes possible? How do African leaders challenge Western initiatives aimed at undermining continental programmes? What kind of African leaders are needed to drive such projects? These questions seem to be at the core of former president Mbeki’s thinking, and he surely knows that his foundation’s first problem is his own history of ineffective leadership. The arms deal scandal, cataclysmic mistakes regarding the Aids crisis, an unwillingness to sanction or even speak out against Robert Mugabe – these subjects are synonymous with the Mbeki era, and will certainly detract from his foundation’s credibility.

But then maybe the observation is so blatantly obvious as to be devoid already of meaning. If the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation can be constantly accused of doing as much harm as good, if the three largest charitable foundations on Earth have all at some point had their integrity called into question, what does it matter that Thabo Mbeki’s African leadership drive is at odds with his own record as an African leader? Hypocrisy would appear to be the rule with foundations, not the exception, and it might just be that the media’s obsession with consistency in this regard is misplaced.

The irreconcilable paradox intrinsic to all charitable endeavours is just that; irreconcilable. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation can say, on the one hand, that “philanthropy plays an important but limited role” while knowing full well, on the other, that the size of the funds at its disposal is the very source of its power. The paradox exists in the fact that it is about the money – when there’s more of it to distribute, the problem of how to distribute it just becomes bigger, as does the possibility (or inevitability) of mistakes.

The real difference between Thabo Mbeki’s foundation and Bill Gates’s – or Bill Clinton’s, for that matter – is therefore not to be found in the levels of hypocrisy, but in the numbers of zeroes in the endowment. While figures have not yet been forthcoming on what Mbeki has raised, it’s safe to say the eventual total will be nowhere near the foundations’ of the two Bills (the Clinton Foundation, although well outside the world’s wealthiest, had a budget in 2007 of around $60 million). Which of course also means that the Thabo Mbeki Foundation has that much less power to do its work – for good or for unintentional ill.

What’s also interesting about the foundations of Gates, Clinton and Mbeki is that they have Africa in common. The verdict is still out on whether the former two have made any lasting impact on the continent. Mbeki, with his unshakable commitment to the African renaissance and his deep knowledge of the processes and shortcomings of African nations, may be able to make a contribution that far outweighs his limited resources. At the very least, the media should let him try. DM

Read more: “Time to change Africa’s mindset” in the Sowetan, List of wealthiest charitable foundations.

Photo: Then South Africa’s President Thabo Mbeki attends the opening of the summit of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) in Johannesburg, August 16, 2008. REUTERS/Mike Hutchings

Become an Insider

Become an Insider