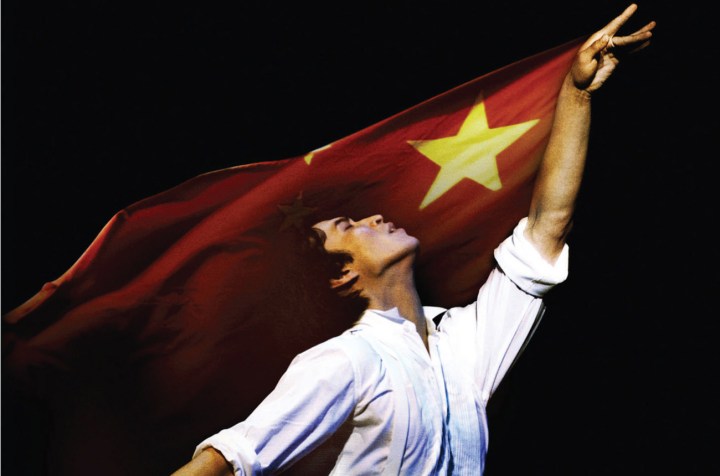

A haunting biographical film about a Chinese ballet dancer who defected to the US during the Reagan years mirrors why South Africans must reject any attempts to muzzle artistic freedom with the zeal that struggle stalwart Albie Sachs envisioned two decades ago.

Last week, The Daily Maverick saw “Mao’s Last Dancer”, the newly released film based on dancer-turned-stockbroker Li Cunxin’s 2003 autobiography. To summarise the plot, in the midst of the turmoil of the Chinese Cultural Revolution that has, as one of its aims, expunging those deviant, alien cultural influences sapping the country’s revolutionary ardour, 11-year old Li is picked from a small village in the eastern province of Shandong to become a boarding student at a Chinese arts school. The Beijing Dance Academy paradoxically specialises in that most Eurocentric of art forms, classical ballet.

Through sheer grit and determination, along with his natural talent, Li becomes an extraordinary dancer. He is selected to join an unprecedented cultural exchange between his school and the Houston Ballet in America just as the political rapprochement between China and America is about to take place.

At the end of his stay in Houston, in a scene that could have come right out of a movie, Li has to step in to dance the lead in the classic work, “Don Quixote”, at the last minute. It’s a cliché first made famous in the Depression era movie “42nd Street”.

Li is a star with the city at his feet, just as he must return to China. He decides to defect – both out of his love for another dancer and his new-found love of artistic freedom. Not surprisingly, this provokes a diplomatic incident that threatens to unravel the still-tentative US-China engagement during the Reagan years. Inevitably too, it takes years of emotional pain before Li is finally allowed to see his parents in China again and revisit his country of birth.

In real life, Li eventually moved to Australia, danced there to great applause, became a stockbroker, wrote his best-selling autobiography and became an international motivational speaker. You couldn’t make this up. And, if you did, nobody would believe it anyway.

The film stars the phenomenal dancing talent of Chi Cao as Li, Joan Chen as Li’s mother, Bruce Greenwood as his Houston Ballet mentor and Kyle MacLachlan as Li’s sleazy, but very effective immigration lawyer. He’s just the kind of guy you wouldn’t invite home for dinner with your family, but who you would definitely want at your side, 24/7, if you were about to be deported from somewhere. Despite the sometimes suspiciously manipulative cinematic devices, the dance scenes are both balletic and athletic enough that they just about take your breath away – unless you abhor dance in any form.

Watch: Mao’s Last Dancer trailer

Bruce Beresford, the veteran Australian filmmaker, directed, and Li and Jan Sardi collaborated on the screenplay. Beresford was a key figure in the Australian film revolution that seemingly came out of nowhere in the 1970s. His first international success was “Breaker Morant”, that wonderfully evocative story about war crimes and the Anglo-Boer War. Later Beresford films include “Driving Miss Daisy”, “Shine” and “Paradise Road”. Sardi worked with Beresford on some of his earlier films including “Shine”. And a footnote for Trekkies: Greenwood played Captain Christopher Pike in the “StarTrek” prequel made in the same year as “Mao’s Last Dancer” was.

For such a visually stunning, entertaining film, many critics seem strangely ambivalent about it. Some have seen in it a Hollywood-style plot to foist a fraudulent, manipulative “freedom equals America” equation on its unwitting audiences. Others have professed themselves shocked and astonished Li wasn’t desperate to return to China and its dangerous, roiling Cultural Revolution, rather than enjoy the material rewards possible with artistic success in the West. Still others have argued the cultural and political struggles of the Cold War and those messy debates about artistic freedom mean very little to us now – this is just so last century. For these people, “Mao’s Last Dancer” should be stowed in that now-overflowing dustbin of history, even if the dancing’s nice.

Ah, but a key supporting character is Jiang Qing – a.k.a. Madame Mao. She doesn’t get much screen time, but she’s the mechanism that actually drives the story forward. Without her, there is no Li in the dance academy and no artistic longings for greater cultural freedom.

Jiang insists on recruiting children likely to be good dancers for her Beijing Dance Academy, but, once they’re trained, she puts the squeeze on the school’s teachers to produce dances with the correct revolutionary fervour and attitude. This sets Li on his first, tentative steps in thinking about artistic and cultural freedom. Moreover, Jiang’s cultural diktats send Li’s most sympathetic teacher off to his rural internal exile because of apparent bourgeois, counter-revolutionary tendencies. And here is where one may define a tendril drawn between South Africa and China.

A little background on Jiang Qing, ‘Madame Mao’, is useful. She was the very model of a modern cultural commissar. She started out as a Chinese version of a B-grade actress-starlet, perhaps a bit like the saga of Evita Peron, but Jiang moved up the ladder with unerring political nous, most notably in becoming Mao Zedong’s last wife. Jiang then used her political power to dictate what did and did not belong in China’s cultural world. Readers may remember those devastating images of professors, artists and writers with signs hung around their necks demonstrating their public ignominy, just before they board trucks to some distant rural location and years of digging holes and then filling them in again.

After helping lead the charge in the Cultural Revolution, Jiang herself was arrested and accused of being counter-revolutionary after Mao’s death in 1976 and she apparently committed suicide in prison in 1991. But before that, during the Cultural Revolution when Mao Zedong had incited students and young workers by arguing that China’s revolution was in danger, Jiang had gained a potent political role.

She led from the front, directing operas and ballets with revolutionary content as part of her effort to transform China’s culture – including one shown with such great effect in “Mao’s Last Dancer”. These works were bravura schlock, perhaps, but they could be immensely exhilarating. Jiang also took charge of the venerable Beijing Opera, pushing her Eight Model Plays depicting the world in stark either/or terms. The good guys were farmers, workers and revolutionary soldiers, the bad guys were those rapacious landlords and cunning anti-revolutionaries.

Photo: Jiang Qing, ‘Madame Mao’.

In a real irony, Jiang also gets credit in helping launch the career of Joan Chen, one of the stars of “Mao’s Last Dancer”, portraying Li’s long-suffering mother. Once Jiang was on trial, she famously told the court, “I was Chairman Mao’s dog. I bit whomever he asked me to bite.” And in her suicide note she reiterated her devotion: “Chairman! I love you! Your loyal student and comrade is coming to see you!”

Shift now to South Africa and the time two decades ago, just as the apartheid era was coming to an end. ANC legal activist Albie Sachs wrote a crucial discussion paper for the ANC, “Preparing Ourselves for Freedom”, that argued a crucial element in the struggle to end apartheid was also the parallel need to create a free intellectual space for cultural figures to operate in, finally escaping the strictures that had penned them in so roughly during apartheid. Although not everyone initially agreed, Sachs’ paper eventually moved liberation movement opinion towards greater artistic freedom – even when creators did not express a political orthodoxy in their work.

Most cultural figures eventually lined up with Sachs when he wrote, “We have sufficient cultural imagination to grasp the rich texture of the free and united South Africa that we have done so much to bring about.” And he declared, only half tongue-in-cheek, that, “Our members should be banned from saying that culture is a weapon of struggle”. Sachs went on to conclude: “What are we fighting for but for the right to express our humanity in all its forms, including our sense of fun and capacity for love and tenderness and our appreciation of the beauty of the world?… [and] …Let us write better poems and make better films and compose better music.” Sadly, Sachs’ article, although it has been reprinted in the book, “Spring is Rebellious”, does not appear to be freely available on the Internet, except through academic publisher, pay-for-view, sites.

Today, while no one expects to see any South African painters wearing signs saying the bearers are class enemies any time soon, some in positions of power might have cheered if the artist who created that updated version of Rembrandt’s “The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp”, featuring a deceased Nelson Mandela, had been forced into acts of public contrition. And then there was minister of arts and culture Lulu Xingwana’s disparaging, angry response to a mildly controversial exhibition of photographs that her own department had funded. Xingwana’s response may be the bellwether of a line that defines what is and is not officially acceptable in art.

And, if the proposed media tribunal that would allow for complaints about published material that could lead to fines or worse, actually comes into being, this may well also have an unintended, but chilling impact on cultural output. Art, just as literature, dance and theatre can be – and probably should be – challenging, disturbing, or even insulting to some. But those so insulted, feeling themselves defamed, may reach to the mooted tribunal to even the score. Thus it should be the duty of cultural creators, just as everyday journalists, to stand in the way of even the first intimations of censorship.

Li Cunxin’s personal experiences and artistic evolution can be a stand-in for a more universal need to defend cultural freedom. Most people can find it easy to support beautiful works; but it will be works that are uncomfortable, irritating – and most especially those that really push boundaries and our buttons – that will need the most support, the most vigorous defence. “Mao’s Last Dancer,” despite its sometimes-mawkish sentimentality, reminds us of the need to defend cultural freedom everywhere, all the time.

By J Brooks Spector

For more on Albie Sachs’ ideas, read Africafiles and Guardian. For more on Jiang Qing, read Wikipedia and Wikipedia. For more on Li Cunxin and the film and book, read his website, ABC.net, Hollywood Reporter. For more on Lulu Xingwana, read M&G, The Daily Maverick. For more on the historical evolution of the ANC’s views on culture, read their website.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider