On the main stage of the Joburg Theatre (the old Civic Theatre), a vigorous, spirited revival of the 40-year-old Andrew Lloyd Webber/Ben Elton musical The Boys in the Photograph has just opened - and runs during the 2010 Fifa World Cup tournament. The goal, obviously, is to lure a good chunk of the hundreds of thousands of foreign and local soccer football fans who will be out in force in South Africa during June and July, all with “the beautiful game” uppermost in their minds.

Photo: The Boys in the Photograph, currently playing in the Johannesburg Theatre.

The Boys in the Photograph is a winsome tale of an amateur football team in Northern Ireland whose priest-coach tries to shield his players from both women (takes the players’ minds off the game) and the violence that has become the prevailing leitmotif of the political reality that surrounds his players. The musical owes a lot to Romeo and Juliet (or West Side Story) – but it is a Romeo and Juliet where we are privy to the inner workings and conflicts of Romeo’s Montague household, even as the Capulets lurk outside in the shadows. And so, we see the story from the Catholic community’s perspective, while the Protestants and the British troops deployed there are most often to be found just over the horizon. But, in contrast to Shakespeare’s or Bernstein/Sondheim’s versions, for The Boys in the Photograph, “girl trouble” is found inside the Montague camp – rather than without. The real, overwhelming threats to life, liberty and any hope for a future are the overlapping religious and political landscapes that engulf the team’s members, their WAGs and their families.

The Boys is not the only cultural effort in this World Cup season that strives to invest a sport with near-metaphysical power and meaning. There are newly commissioned dance works straining for metaphor, outdoor art works on the facades of buildings and a whole range of theatre pieces sponsored by foreign governments all trying to prove that sport is much more than just “how you play the game”. In fact, on behalf of the entire continent and its inhabitants, the African Union declared 2010 to be the year of building peace and security through sport – whatever that may mean.

Weighty proclamations about sport often have some serious, heavyweight history associated with them. American psychologist-philosopher William James famously argued back at the beginning of the 20th century that sports would – or at least should – replace war as a way of organising human competition so that they became “the moral equivalent of war”. That was an optimistic time when any number of political theorists could argue that the very killing capability of modern armies made it impossible for whole nations to throw themselves against each other. Right. Spot on.

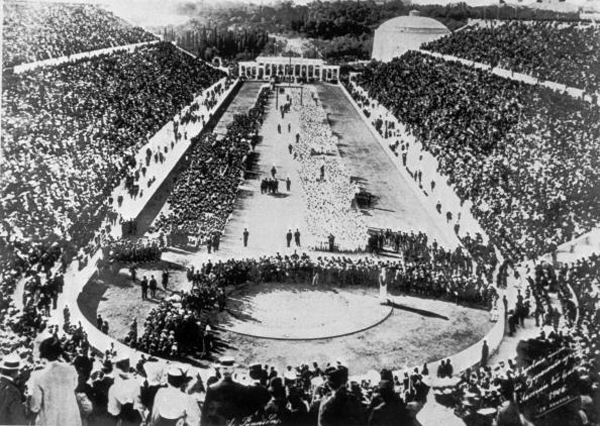

As James wrote in his elegant, flowery Edwardian style: “In a modern era [we] must still subject ourselves collectively to those severities which answer to our real position upon this only partly hospitable globe. We must make new energies and hardihood continue the manliness to which the military mind so faithfully clings.” Or, more prosaically, sport was the new war. And when French Baron Pierre de Coubertin founded the modern Olympic movement in 1894, it was also an expression of a particular view of civilised people who could aspire to a place beyond conflict or warfare, with sports serving as the conveyor belt for reaching that space.

Photo: The opening ceremony of the first modern Olympic Games, Athens, 6 April 1896.

Two world wars, the Holocaust, some miscellaneous genocides and several lethal totalitarianisms later, we know better. Sport and international conflict probably go together almost as well as peanut butter and jam do. Whereas the ancient Greek city-states would cease their interminable wars to carry out their Olympic competitions, the modern world chose to pass on international sporting meetings in order to fight two world wars instead.

Rather than simply being a fun gambol on the Elysian Field, international sport competitions have often become yet another venue for deadly serious political point-scoring, international confrontations, boycotts and terrorism that are an integral part of international conflict more generally. Or, as Peter Alegi, a US scholar on the role of sport in African society, told The Daily Maverick when asked about whether sport could operate beyond the realm of national and international conflicts: “Why would anyone ever think that was the case?”

Photo: Emil Zátopek won the 10,000m race at the first post-WWII Olympic games in London, 1948.

The 1936 Olympics in Berlin were explicitly designed by its Nazi hosts to be a political spectacle of the superiority of the new Germany. Mussolini could call his international football teams his “Imperial Praetorian Guard” as they challenged lesser nations. And in the post-World War II era, the Olympics had its first two organised boycotts in 1956, over both the Soviet invasion of Hungary and Israel’s invasion of the Sinai Peninsula. A generation later, the Mexico Olympics would be the cockpit of the American black power version of the civil rights revolution to the international embarrassment of the US (remember John Carlos and Tommie Smith’s famous clenched fist, black power salutes after winning their races); there were climactic basketball and ice hockey matches between the US and USSR that were stand-ins for a larger international conflict; and there was that infamous and bloody water polo match between the Soviet Union and Hungary – also in 1956 – as a Hungarian team tried to achieve at least a moral victory over Russia’s tanks. And, of course, there will always be the nightmare of Munich.

Photo: Tommie Smith and John Carlos's famous black power salutes after the 200m race in Mexico, 16 October 1968. Smith's winning time, 19.83 sec, was the first sub-20sec race ever.

More than most people, however, South Africans know about the intersection of sports and politics. Back to when Rev Trevor Huddleston first proposed his academic, cultural, trade – and sporting – boycotts of South Africa in 1954 to protest against apartheid, this campaign led to South Africa’s expulsion from the Olympics, as well as retribution against New Zealand at the Commonwealth Games for participating in international sports matches with then-apartheid South Africa.

Several years after the end of National Party rule and the old regime, former president FW de Klerk could finally tell an audience that, while the army and police could not be defeated by Umkhonto we Sizwe, the fact was that, if things kept on going as they were, his government could no longer promise the next generation of its (white) citizens a quality of life that approached that of their parents. Moreover, it also became clear that the country would have to content itself with the crumbs of international sports competition (rugby against the mighty Paraguay?). And so, as De Klerk told his audience, these baleful evaluations about the future helped impel negotiation with the ANC.

Meanwhile, for the opposition, of course, the slogan, “no normal sport in an abnormal society”, provided a crucial rallying cry for domestic and international opposition to the apartheid regime via sport boycotts and protests. The lure of a return to the Olympics in 1992, then, became a critical element in giving a glimpse of the possible benefits that could accrue from a racial and political settlement.

Photo: Sam Ramsamy was leading the call for Zola Budd's exclusion from 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games. (Reuters)

In fact, international sports competitions are so intensely political that even the flags teams compete on behalf of can become fraught with tensions reflective of larger conflicts. South Africa’s return to the Olympics meant carrying the Olympic banner in lieu of a contested national flag, and the use of Beethoven’s 9th symphony music set to Schiller’s “Ode to Joy” had to stand in place of a national anthem. When the Korean Peninsula’s two antagonistic nations compete together as one team, the flag/anthem issue must be confronted. And, of course, athletes from Taiwan march on behalf of a flag of a non-existent (or at least unrecognised) entity with no national flag either.

Beyond fighting national battles, upholding a wounded national pride or on behalf of efforts to end a hated regime, international sports competitions become a creative use of Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz’s famous dictum about war: Hosting an Olympics or a World Cup is the extension of diplomacy by other means.

Don’t believe this? Ask the El Salvadorians or Hondurans – they went to war over the results of a soccer game.

And remember, too, Germany’s World Cup four years ago was explicitly designed to demonstrate that the bad old Germany, eager for war, territory, racial purity and glory was gone, finished, kaput! In the same way, Japan’s 1964 Olympics was designed as a decisive statement that Japan had forever renounced war on China and the rest of Asia (not to mention the US) after that unpleasantness two decades earlier. From now on, the only thing its Asian neighbours and sometime-victims had to fear was a growing deluge of cameras, cars and increasingly clever electronic appliances.

Those who made the successful bid to host next month’s World Cup South Africa – along with all who have joined the subsequent clamour – have clearly hoped that, almost regardless of the cost, this tourney would demonstrate South Africa’s self-appointed membership in the international big boys’ club. And so, as long as the country’s fractured transportation network, it fragile electric grid, policing, healthcare system, telecommunications and the rest of its crucial physical and social infrastructure, as well as its oft-fraught race relations, survive the incoming tide of foreigners, there is a chance that a gain for “Brand South Africa” may just outweigh the griping from this nation’s famously contentious citizenry.

By J Brooks Spector

For more, read: discussion papers from the ANC conference on international anti-apartheid movements, (a wide range of papers on international anti-apartheid activities, including the author’s paper: “Non-Traditional Diplomacy: Cultural, Academic and Sports Boycotts and Change in South Africa”) the official Fifa and Olympics websites, Wikipedia on the Olympic movement and the Commonwealth Games, Peter Alegi’s Alan Paton Memorial Lecture speech on sports and politics in South Africa, the Times obituary on Dennis Brutus, William James’ “The Moral Equivalent of War", Trevor Huddleston’s “Naught For Your Comfort", and the website for the Really Useful Group – Andrew Lloyd Webber’s home site with information on “The Boys in the Photograph” – and the Joburg Theatre’s website on the same musical.

Main photo: Sweden's Pontus Wernbloom (L) fights for the ball with Bosnia's Adnan Mravac (21) during their friendly international soccer match in Stockholm May 29, 2010. REUTERS/Fredrik Persson