Politics

Farewell to giants of our own time

Some South Africans are not content with their lot. They look inside themselves and see that there is so much to do they simply cannot let things take their easy course. Sadly, in less than a fortnight, South Africa has lost two of the best of these, Sheena Duncan and Frederik van Zyl Slabbert

First was Sheena Duncan, a pillar of the Black Sash, that most perennial of anti-apartheid NGOs. And on Friday, it was Frederik van Zyl Slabbert’s turn to leave.

For half a century, the very names – Black Sash and Sheena Duncan – were inseparable. The organisation gained its name from the emblematic black sashes its members wore as they stood at strategic points on major roads, first in silent protests against the growing diminution of the limited voting rights accorded a handful of South Africa’s coloured people; and then later, in increasingly vehement protest against further outrages of the civil and human rights of disenfranchised black South Africans.

Eventually the Black Sash’s resolute stand became a symbol for what good people could do in very bad times. Beyond mere protests, Sheena Duncan (under the steely influence and example of her redoubtable mother, Jean Sinclair, a founder member of the Black Sash) and her organisation eventually became a kind of “ground zero” in dealing with the concrete effects of the apartheid regime’s laws on the lives of ordinary people. Black Sash’s advice offices offered help to millions of people flummoxed, then harried and hemmed in by the insane intricacies of the Group Areas Act, the pass laws and all the rest of their kind.

In recent years, to those who may not have known better or who had no understanding of history, it may have seemed the Black Sash’s time had come and gone. But instead the organisation adroitly reinvented itself offering still-crucial advice, guidance and authoritative information on how to cope with the complexities of the new government’s protections and benefits that while, ostensibly, available to all, were virtually impenetrable for many to negotiate successfully. The benches of Black Sash advice centres remain filled.

Photo: The Black Sash has tirelessly campaigned for justice and equality throughout South Africa for over 50 years.

Frederik van Zyl Slabbert, meanwhile, followed the well-worn path that articulate young white Afrikaner men took in those days. After one of those successful high school careers with roles as head boy and captain of the school’s rugby and cricket teams, he entered the University of the Witwatersrand to study the classics, with an eye to becoming a Dutch Reformed Church minister. But, soon enough, he transferred to Stellenbosch University, Afrikanerdom’s premier educational institution, to study sociology. He became a lecturer, first at his alma mater, then at Rhodes, back to Stellenbosch, then to the University of Cape Town and finally on to Wits.

Sociology and the influence of religious thought eventually drove him away from any support for apartheid. And so, in 1974, he ran for Parliament under the opposition Progressive Party’s banner for the Cape Town neighbourhood of Rondebosch where he was the surprise winner over the old United Party’s candidate. As the “Progs” morphed into the Progressive Federal Party, with Van Zyl Slabbert as its new parliamentary leader, he helped shape the party’s ideology into an increasingly strident opposition to the National Party government, and all its laws and states of emergency.

But then, in 1986, in a shock to the national political class, Van Zyl Slabbert voluntarily surrendered his parliamentary role. He had come to believe that “normal” governmental institutions such as parliament had become irrelevant to solving South Africa’s political, social and economic dilemmas. He set these views out in his widely read and controversial book, “The Last White Parliament”.

A year later, he was director of policy and planning for the Institute for a Democratic South Africa and became convinced South Africa urgently needed to engage with the exiled ANC. He became a key figure in convening the conference in Dakar, Senegal, that, in spite of unrelenting criticism from the National Party government, brought together the ANC and dozens of South Africa’s leading politicians, academics and businessmen for the first time.

Through the 1990s, even though a new generation was coming to the fore, Van Zyl Slabbert remained active in identifying and exploring the agenda by which South Africans would define their joint future, through his speeches, participation in public debates, in electronic media appearances and via his many articles and books. Van Zyl Slabbert worked with the George Soros-funded Open Society Foundation of Southern Africa, he became a co-founder of Khula, a black investment vehicle, and he joined the boards of various companies as well.

In books like “Comrades in Business: Post-Liberation Politics in South Africa” (co-authored with Heribert Adam and Kogila Moodley), “Tough Choices: Reflections of an Afrikaner African”, and “The Other Side of History: An Anecdotal Reflection on Political Transition in South Africa” which he edited, he set out a view of his personal political choices and his ideas about the way forward for the newest version of South Africa.

Van Zyl Slabbert was a prime example of the politically engaged public intellectual. In stark contrast to his own vigorous efforts to identify and then embrace the political and social changes he believed to be crucial – and which he had helped give birth to – Van Zyl Slabbert once tartly observed of his long-time political nemesis, PW Botha, that, “Circumstances forced him to be a reformer. He was extremely authoritative, militant and not very well read; he relied heavily on the people around him. He started the process of dialogue with the ANC, but this was behind the scenes and very hush-hush.”

It is a measure of Van Zyl Slabbert’s importance and influence that he helped lead the country’s great change, exposed and out in the open. Teddy Roosevelt would certainly have said of him he was “the man in the arena”.

Hamba kahle Sheena Duncan. Hamba kahle Frederik Van Zyl Slabbert. And thank you, dankie and siyabonga to you both.

By J Brooks Spector

For more, read: Wikipedia, AP, SAHistory.org, SAHistory.org, Whoswhosa, and the Black Sash and Idasa websites

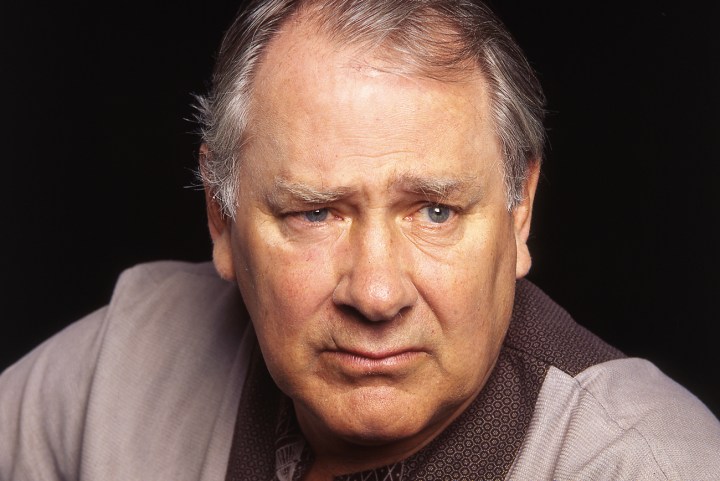

Main: Frederik van Zyl Slabbert, a photo used for February 2007 cover of Maverick magazine. Photo: Sally Shorkend.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider