Politics

The Group Areas Act, Freedom Day’s sad, angry antecedent

As the country celebrated its Freedom Day on Tuesday, there was another anniversary to be marked: 60 years of The Group Areas Act, a crucial piece in the truly monstrous puzzle that was apartheid.

Only the most extraordinary cynic would have stayed dry-eyed and unmoved 16 years ago on 27 April 1994. South Africans of all backgrounds stood together in those enormous queues that snaked for kilometres through the open veldt or wrapped around whole city blocks to reach polling stations as South Africans voted as one nation – reversing the apartheid regime that had held sway since 1948.

The aerial photographs of that momentous national civic event have become universal, iconic statements of how, given just a bit of luck, a nation can come together rather than tear itself apart through civil war.

In the half-century before that mesmerising moment, apartheid became a legislative thicket that bound together legal and customary social practices from the years before 1948, resting upon the country’s colonial past and its legacy of slavery. Apartheid became a vast, intricate, interlocking, authoritarian system of legal, political and economic domination by white South Africans over the country’s black inhabitants – enforced by a veritable army of civil servants. By various counts, by the mid-1970s there had been some 17 million convictions for infractions of the pass laws – the domestic passport imposed upon every African and that governed part of nearly every African’s whole life.

When the National Party took power in 1948, it imposed laws that, one after another, isolated and subjugated the nation’s black population. First up was The Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act of 1949, followed 1950 by the Immorality Act that made it a criminal offence for a white person to have sexual relations with a person of a different race. These were followed by The Population Registration Act of 1950 requiring all inhabitants to register with authorities in accord with their respective “races”, then The Suppression of Communism Act that gave the government the right to ban any opposition party or group that it chose to identify as “communist”.

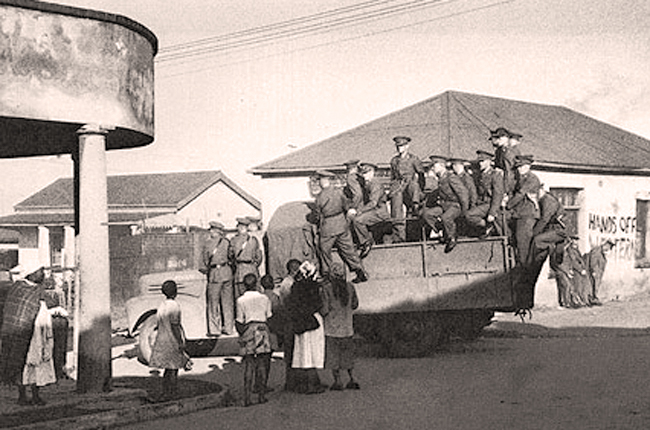

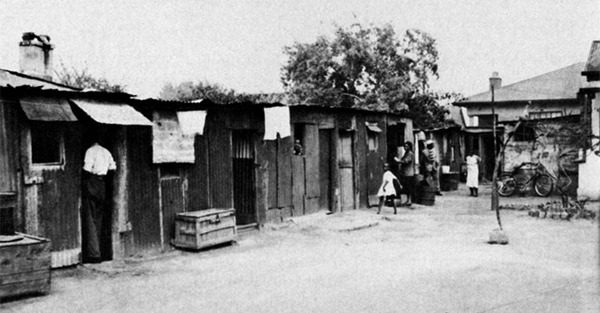

Photo: Sophiatown, 1950 (The Star)

And then, exactly 60 years ago – the same day as the first free national vote 44 years later – the National Party passed The Group Areas Act that located every person in specific terms as to where they could live, buy or rent property on an implacable, racially defined map – and thus, too, where any person could not live, buy or rent property.

This inevitably meant many had to move – and fast – when they were then, suddenly, in what was defined as the “wrong” place. The underlying legal principles were eventually undermined by drawn-out legal battles in the 1980s that legitimised what was becoming an economic and geographic truth, regardless of the law. Black South Africans were illicitly moving into proscribed parts of the country’s cities as they sought better housing to be closer to schools and work.

Back in 1950, though, the rest of an entire legal avalanche soon followed The Group Areas Act: The Separate Amenities Act, The Bantu Education Act, The Mines and Works Act, The Promotion of Black Self-Government Act, The Extension of Universities Act and The Black Homeland Citizenship Act – among others. Go to the Apartheid Museum to see a whole wall – literally – of the entire panoply of racial legislation that was apartheid.

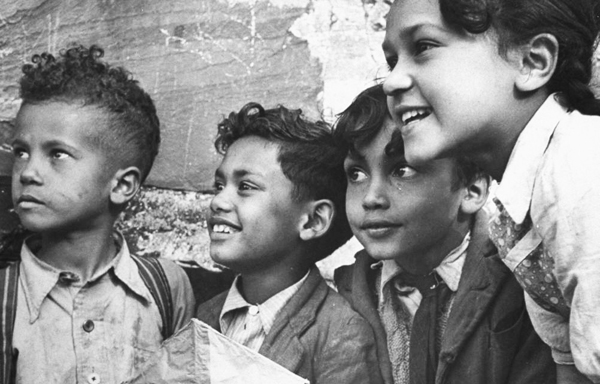

Photo: South African children playing and laughing in the tough streets of District 6. (LIFE magazine)

It was a particular genius of the National Party government that, just as Lewis Carroll’s “Queen of Hearts”, words came to take on whole new meanings and meant whatever the government said they meant. The Extension of Universities Act further restricted attendance at the handful of previously less-segregated universities. The Promotion of Black Self-Government Act further restricted participation in civic affairs. The Bantu Education Act shuttered any church-run schools whose directors were unwilling to adhere to strict segregationist policies, thereby further limiting educational opportunities.

But, it can be argued that the Group Areas Act was the big one, defining in precise, intricate geographical terms what was and was not allowed with little or no pretence that it was somehow designed to be an equal division of the land – and gave everything else that was in apartheid’s system an actual location to take effect.

But besides a more generalised legacy of anger and sadness over what happened as a result of the Group Areas Act that infected three generations nationally, whole communities in – Sophiatown, District 6, Marabastad, Pageview, Vrededorp to name just a few – were forcibly moved out of long-time residences to distant sites with far too little by way of amenities or services. Such movements did at least give us some wonderfully sad, poignant writing, theatre and music – the anthem “Meadowlands, Meadowlands”, musicals like “Sophiatown” and “District 6”, novels like “Buckingham Palace – District 6”, memoirs like “Down Second Avenue”. But these must be counted as little consolation.

Ironically, in ways that apartheid’s planners and enforcers never imagined, one of the Group Areas Act’s biggest legacies is one with which the current government must continue to wrestle – an urban prospect that was widely and distantly scattered across the landscape. Service delivery – electricity, transportation, water, sanitation – has become a costly nightmare for city planners and urban administrators, and contributes to a low-density urban sprawl that has become a defining feature of the South African cityscape today.

By J Brooks Spector

For more, check out the Apartheid Museum website, the SA History Archive, the SA Institute of Race Relations’ historical archives and yearbooks, the Durban Conference on International Anti-Apartheid Movements in SA’s Freedom Struggle, or the ANC’s electronic collection of historical documents, among many other sources.

Main photo: Sophiatown, 1950

Become an Insider

Become an Insider