South Africa

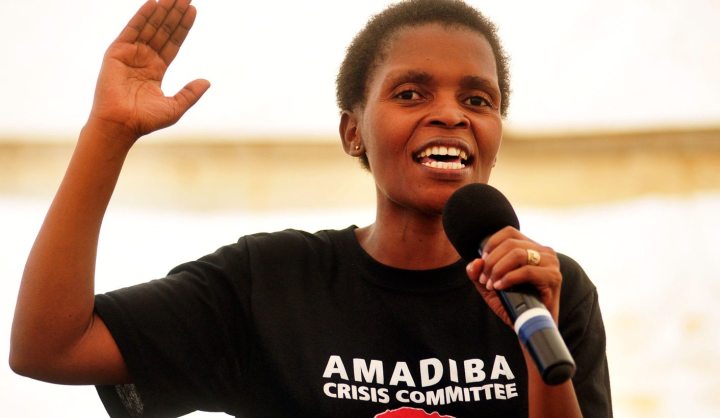

Wild Coast anti-mining activist Nonhle Mbuthuma: ‘They must kill me alone, not with my family’

Gunfire reverberated through the valleys of the Wild Coast as residents paid homage to slain anti-mining activist Sikhosiphi Bazooka Rhadebe, who was assassinated in March 2016. An 18-month moratorium on mining activity and applications in the area has done little to end hostilities, writes LUCAS LEDWABA.

Nonhle Mbuthuma knows there is a bullet with her name on it. Early last year she got wind of news that her name was among those of three leaders of the Amadiba Crisis Committee (ACC) who were on a hit list in the raging battle over the granting of mineral mining rights in Xolobeni, Eastern Cape.

On the advice of her family and the ACC leadership, she immediately went into hiding. She has been living on the run since then. Yet she remains active in the struggle against the granting of mining mineral rights in the area along the Wild Coast.

.jpg)

Photo: Amadiba protesters (Photo: Lucas Ledwaba)

But one of the three men on the hit list, Sikhosiphi “Bazooka” Rhadebe, was not so lucky. On March 22 last year, two men masquerading as policemen arrived at his home in the dead of night and shot him eight times.

He died, the blood from his gaping wounds seeping into the soil of Mngungundlovu, his place of birth which forms part of the area earmarked for mining.

Photo: Bazooka’s grave, a year later. (Photo: Lucas Ledwaba)

Photo: Xolobeni activists with Bazooka portraits. (Photo: Lucas Ledwaba)

It’s been a year since the killing, and Mbuthuma has known no normal family life since then. She moves from hiding place to hiding place in a bid to stay ahead of those who want her dead. With every day that rises and sets, she is thankful. The fear of the prowling assassins has been replaced by a steely resolve to continue the fight to preserve the land of her birth.

“It’s not that I’m hiding because I’m scared, no, but for the sake of my family because I know they are targeting me right now. So, when they kill me they must kill me alone, not my family.”

The choice of the word “when” rather than “if they kill me” is a chilling admission that, like Bazooka and others, she has accepted that her activism may result in her paying the ultimate price – being struck down by an assassin’s bullet. But she is not giving up. Although she is resolute about her continued role in the struggle, she concedes that this life of being hunted down like an animal has taken a huge toll on her.

“This struggle is very stressful. Sometimes you don’t even know yourself because of the stress. After they killed Bazooka I was more strong and brave. [Fear] is not going to solve the problem. What is the reason of being scared to die? Other leaders have already been killed,” she says on the sidelines of a ceremony to repatriate Bazooka’s spirit at his homestead in Mngungundlovu.

Mbuthuma mentions the names of some of her slain comrades like a roll of honour of men of valour. The community puts the number of those who have died since the stand-off started at the turn of the millennium – between those for and against the proposed mining of titanium in the area’s red sand dunes – at 12. Some were shot and others, they say, were poisoned.

“Madoda Ndovela was shot in early 2000,” says Mbuthuma. “It was very strange because we don’t have such crimes here. Scorpion Ndimane was poisoned. Bala Sheleli…” she says, looking away into the distance where the great hills twist and curve gently before descending into the great Indian Ocean a few kilometres away.

She says Bazooka, a fierce and fearless opponent of the proposed mining, was targeted largely because he used some of the proceeds and resources from his taxi business to help the locals with their struggle against the granting of mining rights to Australian-owned Transworld Energy and Minerals [TEM] and the Xolobeni Empowerment Company [Xolco] in 2008.

The project, known as the Xolobeni Mineral Sands Project, was put on hold after Minister of Mineral Resources Mosebenzi Zwane imposed an 18-month moratorium on the development in September 2016 following fierce resistance from the ACC and the many of the locals. But this has done very little to restore normality to the area. Instead, fear, suspicion and uncertainty continue to haunt the once peaceful area of more than 240,000 people living on one of the country’s most stunning coastlines. Brother has turned against brother, sister against sister and father against son between those against and those for the mining of titanium.

“Killing him, they thought, would be the end of the struggle. But it seems the killing has had the opposite effect. Our strategy now after Bazooka’s death is that we will not allow any mining to happen here,” fires Mbuthuma.

Photo: Pondoland veteran. (Photo: Lucas Ledwaba)

She longs for the peace and spirit of kinship that existed before talk of the mining brought bitter division, mistrust, hatred and pain to the area.

“Oooh! You know life before this [mining stand-off] was sweet, nice. I wish I could go back to those days. We had trust in each other, [we] loved each other,” she says, reflecting on a past that is now gone and, it seems, may never return.

“But today that trust is gone, finished! We don’t even trust our own relatives. It has destroyed family relationships. [For instance] If I know my brother is conducting a ceremony and he is a supporter of the mining, even funerals, you don’t attend because you might be poisoned.”

Photo: Herdsman (Photo: Lucas Ledwaba)

While others like Bazooka died in a hail of gunfire, elders like Samson Gampe, a veteran of the 1960 Pondoland revolt, have died supposedly as a result of the strain of having to live with the thought that they may one day be ejected from their land to make way for mining.

“He died from a broken heart,” says Gampe’s daughter Bawinile Mchebi. “He was always worrying about this mining problem.”

Gampe, a herbalist and healer, died in January 2017, apparently from heart complications which his daughter believes were caused by the constant worrying about losing the only home he knew. He knew the land like he knew himself and often travelled great distances on foot, prowling the great hills and coastline to harvest indigenous herbs.

In 1960, he was among Pondo men who took up arms against the apartheid regime’s efforts to gain more control of their land and impose restrictions on their old way of life, including the amount of land they owned and the number of livestock they could keep.

According to South African History Online the Pondo people opposed the implementation of the land reclamation programme which was to have a serious structural impact on their way of lives in that their lands would now be divided up and presided over by chiefs and magistrates chosen by the apartheid government.

Scores of people died when the government reacted to the revolt by declaring a state of emergency and massacring a gathering of Mpondo men. Gampe survived the onslaught and when the mining crisis started in the early 2000s, he joined this new struggle to protect his land.

“My father was deeply hurt by this threat over our land. He said he had fought and others had died [in 1960]. He didn’t want to be separated from the land,” says Mchebi.

She too is opposed to mining in the area based on what she experienced during a visit to a Gauteng community affected by mining some years ago.

“I saw people living in shacks, hungry people, too many children without parents. We do not want something like that happening here,” she says.

Like her late father, she wants to continue living off the land, in peace, without the complications often brought about by mining.

“My father had cattle, horses. He was a herbalist who knew all the plants. He has taught me this gift. We even travelled with him to the sea to harvest herbs. But now we are always worried.”

Mfihlelwa Mnyamane, also a veteran of the 1960 revolt, has a breathtaking view of the spectacular landscape. His homestead is perched on the slope of one of the countless grassy hills that protrude from the land like bubbles.

He has an undisturbed view of the blue waters of the Indian Ocean two kilometres away. The soft, clean breeze from the ocean sweeps through his homestead daily.

Back in 1960 he was a young man in his 20s. Even then, he was conscious of the importance of what the land means to his people.

“So many, so many people died during that time. We were really angry. The Boers wanted to take over our land and make it theirs. Now, many years later, we see this same thing happening again here,” says Mnyamane, standing on the edges of his homestead on a sunny, windy day.

“Between 1960 and 1961 we really fought hard. We cannot now give away the land over the bodies of so many people who have died. In 1994 Mandela helped us to achieve our freedom. He knew what pain we went through in 1960 because he was also arrested for fighting for the land. Now we cannot allow mining here,” he says.

Mnyamane has vague memories of ANC leader Oliver Tambo visiting the area during the revolt in 1960, when a committee was formed known as iKongo, a Xhosa adaptation of Congress in the name African National Congress (ANC).

The revolt had been led by peasants and it was only when the ANC aligned itself with the uprising that the name iKongo became synonymous with the struggle of the Pondo people.

But now a new attempt to take away the land of the Amadiba, who form part of the Pondo people, is happening under the watch of the ANC government.

“The ANC knows where we come from. We do not expect that they will allow something like this to happen again where our land is taken away,” says Mnyamane, who speaks fondly of his former comrades in the revolt.

But today, just like Mnyamane took up the struggle as a young man in the ‘60s, young men like Siyabonga Ndovela, 24, are leading the charge to protect their land regardless of the threat anti-mining activists face.

On Human Rights Day, he was leading a crowd of youth and adults descending on Bazooka’s homestead, singing a song whose lyrics speaks of the frustration of the locals opposed to mining.

Arrest them, deny them bail because they are killing us, goes the song in Xhosa.

“They are targeting our leaders,” says Ndovela. “This talk of mining has really divided us. It is really bad here. If you are against mining you will be targeted. But the land is everything to us. We work the land. We eat from the land. Mining is not going to bring that for us. We cannot, as young people, allow our land, the land of our ancestors and our children, to be taken over by strangers.”

Another young man, aged 22 and fearful of being named, sums up the practicality of the refusal to part with the land and the fears of the locals.

“Every day I eat fresh fish from the ocean, free fish. Our food comes from the land. I fear that wherever they take us, who is going to take care of us? I was born here, raised here and now I am an adult and I do not want to be separated from this land.”

Like the elders, he believes even the dead who lie buried in the soil of this land remain linked to the living.

“My grandfather’s grave is up there on that hill. We cannot be separated from our ancestors. We rely on them for guidance and protection all the time.”

Mbuthuma says they are baffled that government would allow open-cast mining, which is set to consume a lot of water from both rivers and underground sources that sustain the local populace, to continue in such an environmentally delicate area.

“What will happen to us humans when they finish all the water? Mining will bring us drought.”

As South Africa observed Human Rights Day, just exactly one year shy of the day since Bazooka’s killing, gunshots reverberated through the picturesque valleys of the Wild Coast as scores of people gathered to remember his life.

Pistols were fired into the air as Bazooka’s family performed traditional rites to repatriate his spirit back to his homestead where he lies buried and hundreds chanted and sang in praise of the man they held in awe for his bravery and unyielding spirit of leadership.

Although this was only a ceremonial crackling of gunfire to appease Bazooka’s spirit, every day people in the area continue to live in fear of who would be at the receiving end of the next burst of gunfire. – Mukurukuru Media DM

Main Photo: Nonhle Mbuthuma (Lucas Ledwaba)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider