Politics, South Africa

Analysis: Moral Equivalence in International Relations

South Africa’s withdrawal from the ICC constitutes a commentary on the nature of the legal global order. The absence of a moral equivalence in the implementation of legal principles across all countries regardless of size and political and economic endowment has an immediate effect on the internalisation of the global legal regime as inherently biased. By Dr AMY NIANG, Department of International Relations, Wits University.

Although not entirely unexpected, South Africa’s announcement that it has taken steps to withdraw from the Rome Statute, the founding treaty of the International Criminal Court or ICC, has baffled many observers. South Africa is generally seen as a champion of human rights given its liberal Constitution, the existence of a strong civil society advocacy for the advancement of a variety of rights, and its history of struggle against apartheid, a legal and moral regime that was founded on the very violation of fundamental rights. Given South Africa’s active role in the elaboration of the Rome Statute, the latter has to be seen as deeply influenced by the history of anti-apartheid struggle.

South Africa’s International Relations and Co-operation Minister, Maite Nkoana-Mashabane, invoked a legal conflict between international customary law that guarantees diplomatic immunity to sitting heads of state on one hand, and South Africa’s legal obligations under the Rome Statute on another. According to Justice Minister Michael Masutha, these obligations undermine South Africa’s ability to promote “peace, stability and dialogue [on the continent]”. The decision follows in fact a request made by South Africa for clarity on conflicting immunity obligations at the Assembly of States Parties held in The Hague in 2015.

If the immediate cause of withdrawal has therefore to do with the political and legal aftermath of South Africa’s refusal to arrest Omar al-Bashir during his attendance of the AU meeting in Johannesburg in June 2015, the problem is arguably more complex. The legal argument barely conceals a political protest against the ICC’s discriminate focus on African perpetrators of international crimes.

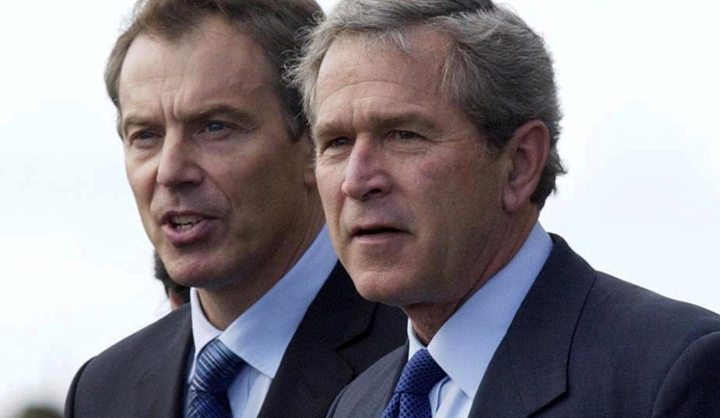

The ICC operates in the context of a global governance structure characterised by a problematic multilateralism, the prevalence of Northern hegemony, and an implicit hierarchical moral and racial order that makes it acceptable for African leaders to be prosecuted but makes the indictment of American or British leaders inconceivable. In 2011, Amnesty International called for Tony Blair and George W. Bush to be tried by the ICC as war criminals for atrocities committed in Iraq and Afghanistan. Nobody believed for a second that these leaders would ever be brought to book.

Insofar as Africa is concerned, the African Union will have to implement the 2014 Malabo Protocol in order to enable the African Court of Justice and Human Rights to prosecute crimes under international law and transnational crimes if it is to be taken seriously. The recent prosecution of Hissène Habré at the Extraordinary African Chamber in Dakar for crimes of war is evidence that where there is political will and the adequate resources, the cause of justice can be advanced on the continent. The current conjecture is therefore far from being straightforward; it is not to oppose immunity to impunity but rather to denounce moral hypocrisy, double standards and racialised determinations.

African and other developing states’ initial enthusiastic support for the ICC was motivated by a desire to have a collective instrument, unhindered by a veto-system and capable of reining in even the most powerful states, to subject therefore everybody to the same universal rules, to deliver global justice and to advance universality. Instead, the court has turned to the continent as a place of prosecutorial experimentation and this is partly what is being objected to.

The prospects are enormous for the ICC’s capacity to help bring justice to millions of victims in Palestine, Afghanistan, Libya, and other parts of the world but until the issues of fairness, competency, and procedural deficit are addressed, this will remain an unfulfilled possibility. The fundamental question here is not whether more African states are likely to pull out. They are. In fact, an exodus is very likely. The bigger issue however is that the implementation of the Rome Statute in its current form suffers from many “technical” deficiencies including shortcomings in the operations of the Office of the Prosecutor (OTP). Until big powers such as the United States, China and Russia come on board to help the ICC mitigate these shortcomings, the court will continue to lose moral legitimacy, therefore relevance.

Given this context, African states do have a legitimate ground in denouncing the ICC’s disproportionate focus on African perpetrators of crimes – seen as easy targets. Of the 10 countries currently being investigated by the ICC, nine are African. The fact that some of these cases were referred to the court by African states themselves does not justify current prosecutorial configurations. What this tendency also does is to perpetuate an image of African leaders as corrupt villains who prey over their populations even when the most egregious crimes have been or are being committed in Colombia, Yemen, Chechnya, Syria, and Iraq, to name a few, most of which involve dominant powers such as the United States, Russia, and France.

As a treaty court, the ICC prosecutes perpetrators of war crime, genocide and gross violations of human rights where states have voluntarily referred cases to the court. While the court cannot adjudicate on crimes perpetrated by non-member states, the fact that cases can also be referred by the UN Security Council opens up space for third-part interference. This is in fact the situation that has led to the referral of Omar al-Bashir to the ICC by the UNSC for charges of genocide and crimes against humanity in Darfur.

There are a couple of things at issue here. First, South Africa’s withdrawal has to be seen as a significant protest gesture against ICC bias against African leaders. While UNSC members are happy to make referrals to the ICC, they do not trust the same court to render justice where their state and military officials have been involved. Second, while any move that undermines the prosecution of perpetrators of peremptory crimes has to be seen as a moral and legal regression, the reluctance of the international community to recognise and address this bias and related procedural deficiencies is bound to lead to more withdrawals.

More crucially, South Africa’s withdrawal from the ICC constitutes a commentary on the nature of the legal global order. The absence of a moral equivalence in the implementation of legal principles across all countries regardless of size and political and economic endowment has an immediate effect on the internalisation of the global legal regime as inherently biased. The global order is constrained by an absence of parallelism as a principle of international relations. Parallelism requires that the same jurisprudential rules and system of values, the same equivalent norms, be applied fairly and evenly in relation to all states.

Legal scholars often take for granted the normativity of “The Law” and treat “politics” as an inferior domain that merely interferes with the pursuit of “justice”. However, in fighting “the most serious crimes of concern to the international community”, as the founding charter has tasked the court, it has to be recognised that extrajudicial demands have come to compromise the status – and now the future – of a needed judicial institution. DM

Photo: British Prime Minister Tony Blair (left) and then US President George W. Bush at Azores, Sunday 16 March 2003, where they held talks over Iraq. EPA PHOTO.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider