Africa, South Africa, World

Justice minister confirms ICC exit, and defends the indefensible

It’s official: South Africa has withdrawn from the ICC. At least that’s what government said, with justice minister Michael Masutha sent out to defend the sudden decision. But civil society groups are planning to challenge the lawfulness of the withdrawal – because parliament was not consulted – and ultimately Masutha’s briefing raised more questions than answers. By SIMON ALLISON.

Justice minister Michael Masutha had the most difficult job in South Africa on Friday morning. It was his unenviable task to confirm to world media that South Africa had indeed commenced the withdrawal process from the Rome Statute that constitutes the International Criminal Court (ICC); and to explain why this country – once a beacon of liberal ideals – was turning its back on an institution designed to hold war criminals to account, and to deliver justice for their victims.

He made a valiant effort to defend the indefensible. According to Masutha, the withdrawal was an abandonment of South Africa’s moral authority, but rather the opposite. The Court, he said, was making it harder for South Africa to pursue peace and security in Africa because it strips leaders of their diplomatic immunity. This means that South Africa can’t invite dodgy presidents and rebel leaders to peace talks on South African soil.

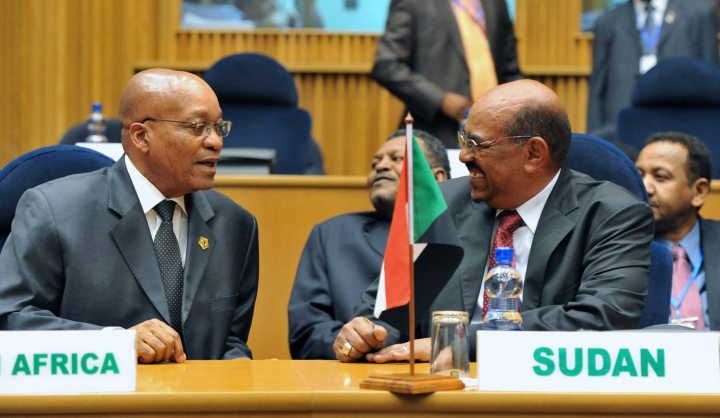

“Our international policy outlook is focussed on promoting peace and stability…the legal uncertainty continues to hinder this country from being able to host such activities in our country,” he said, using Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir’s controversial visit to Johannesburg last year as his example. Bashir is wanted for war crimes by the ICC, but South Africa failed to arrest the Sudanese leader.

Mashuda’s argument sounds good at first listen, but it doesn’t really hold up. For one thing, as Zuma outlined earlier this week at a meeting of South African ambassadors, South Africa’s foreign policy priorities are almost entirely economic, with peace and security considerations very much a secondary concern. For another, South Africa is currently involved in several conflict resolution efforts – for instance in Lesotho and in South Sudan – that have not obviously been hampered by any lack of diplomatic immunity available in South Africa. There are clearly ways around the diplomatic immunity issue that do not require a wholesale abandonment of the ICC. Even in Sudan, former President Thabo Mbeki continues to engage with various leaders through regular visits to the country itself.

The other sticky issue confronted by Masutha was whether the notice of withdrawal was even legal. Does the President really have the power to remove the country from such a major international treaty without consulting parliament first?

“In terms of our constitution, and it is equally as we understand it in terms of international law as it currently applies in practice, the authority to negotiate entering into and actually signing international instruments is the preserve of the executive… it stands to reason that given the prerogative of the executive to enter into international agreements, it is equally the prerogative of the executive to withdraw from such agreements,” he said. Masutha said that Parliament would be officially informed of the executive decision, and that a bill to repeal the domestication of the Rome Statute will be submitted soon for consideration.

Chief State Law Adviser Enver Daniels confirmed to the Daily Maverick that the government had sought both internal and external legal opinions on this issue, and was 100% confident of its legal standing. Other legal experts are not so sure. A group of civil society organisations are planning to lodge an urgent application on Friday afternoon challenging the legality of the withdrawal. Their argument, much simplified here, is that because Parliament ratified the treaty – therefore making it legally binding – only Parliament can un-ratify it. If this application is successful, South Africa’s notice of withdrawal can be declared null and void.

Masutha also hinted that the state may withdraw its Constitutional Court appeal on the Bashir case. The state has been trying to overturn earlier court judgments that its failure to arrest Bashir was unlawful, but may not now feel the need to press the point: the legal issue over whether the Rome Statute trumps diplomatic immunity is irrelevant if South Africa is no longer part of the Rome Statute. If the appeal is withdrawn, there may be consequences for individuals involved in allowing Bashir to leave South Africa, as this has been declared unlawful. If the appeal does go ahead, South Africa’s notice of withdrawal to the ICC will have no legal bearing on the case.

Overall, Masutha’s briefing raised more questions than answers. He did not address the timing of the withdrawal, or the secrecy around it. He did not comment on the potential influence that President Jacob Zuma’s recent trip to Kenya – the fiercest critic of the ICC on the continent – may have had on the decision (or indeed his recent BRICS engagement. There’s no doubt that Russia in particular would encourage any move that could be considered a snub to the international system). And he sidestepped the question of what remedy would be available to victims of serious international crimes in the absence of the ICC.

There is an answer to this latter question, however, and that’s the real tragedy of South Africa’s decision to withdraw – and the domino effect it could have on other African countries. As yet, there are no other options for victims of war crimes in Africa. The African Union wants to set up its own, similar court, but has neither the money nor the capacity to do so in the near future. In the meantime, South Africa has sent a loud message to war criminals – men like President Bashir – that they can operate with both immunity and impunity. DM

Photo: A photo provided by the South African Government Information Service shows South Africa’s President Jacob Zuma (L) speaking to Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir (R) attending a session of the 24th African Union Summit of the NEPAD Heads of State/Government Orientation Committee (HSGOC) at the African Union Headquaters in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, on 29 January 2011. EPA/Ntswe Mokoena

Become an Insider

Become an Insider