Maverick Life

Thirty years of Graceland: How Paul Simon and the SA music industry created a masterpiece

On the cusp of the 30th anniversary of the release of Paul Simon’s Graceland, J. BROOKS SPECTOR remembers the impact of Simon’s music and the moment when their paths crossed in South Africa.

For several years during my university days, I had a roommate who enjoyed the music of Simon and Garfunkel. Enjoyed is not exactly the right word to use, perhaps. Day after day, week after week, month after month, he played their recordings, Sound of Silence and Scarborough Fair, repeatedly, obsessively, until everyone who lived in that house could sing every word of every song.

During a tempestuous decade, the composer/performer duo, Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel, produced hit after hit, album after album as their songs became deeply lodged in the psyches of young people around the world. They were songs that seemed to channel hopes, fears, and anxieties, without ever speaking to the direct causes of the angst of that age. They didn’t mention Vietnam; they didn’t sing about civil rights abuses; they didn’t decry injustice, poverty and misery like so many folk singers of the time; their sounds just found a path to the heart of things.

Video: Simon and Garfunkel – Sound of Silence – The Graduate

By the time their music became an integral part of the texture of Mike Nichols’ hit film, The Graduate, a work that seemed to zoom in on the lies and prevarications of mid-Sixties America, Simon and Garfunkel’s music seemed to be heard everywhere – from their vast open-air, public concerts to the ubiquitous muzak in lifts and shopping malls. Even in South Africa, despite the apartheid regime’s regimentation of the airwaves, their music reached its many fans.

The two men had come together in mid-fifties as teenagers in a middle-class neighbourhood in the borough of Queens in New York City. After a number of middling successes, the hit gold with their single, The Sound of Silence. Thereafter, they turned out four hugely successful albums, Sounds of Silence, Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme, Bookends and then Bridge over Troubled Water.

But then, by 1970, the two men went their separate ways – Simon to a variety of other recording projects, and Garfunkel on to a mix of music and film acting, but their careers only occasionally brought them together. Notably, their reunion for the 1981 Concert in Central Park was a gig that attracted a crowd estimated at some 750,000 people, proving yet again the duo’s music had serious staying power.

By the mid-1980s, however, Paul Simon’s creative powers increasingly seemed stuck in neutral, and his marriage to actress Carrie Fisher had foundered as well. But in 1984, he received a pirated copy of a cassette recording of South African music – Gumboots: Accordion Jive Hits, Vol. II. As he listened, he found he was improvising scat singing for his own pleasure over the recorded music, music that seemed to him to be reminiscent of 1950s-style rhythm and blues music. Eventually he got his new record company, Warner Bros, to track down the creators of the music, and it was determined the singing on the cassette was from either the group the Boyoyo Boys or a then-still-little-known group, Ladysmith Black Mambazo.

Listen: Boyoyo Boys – Daveyton Special

After discussions with record producer Hilton Rosenthal, Simon began listening to armloads of South African recordings and eventually came to South Africa to meet up with many of those musicians, courtesy of arrangements by Rosenthal, for the possibility of creating a new recording. Just before leaving, Simon had been roped into contributing to We Are the World, the first major international charity recording, a project largely organised by composer/arranger Quincy Jones, with the assistance of singer Harry Belafonte. Before heading off to South Africa, Simon spoke with those two who encouraged him on his planned visit, and he also garnered agreement from the South African musicians’ union for his evolving plans.

Initial recorded tracks of some of the material for an album were made in Johannesburg with such artists as Tao Ea Matsekha, General Shirinda, and the Gaza Sisters, and the eventual album was put together in “final” at The Hit Factory studio in New York City, after yet additional recordings of material in Los Angeles, London and Louisiana (for the Zydeco riffs). Completing the album also meant taking various South African musicians to New York City such as Ladysmith Black Mambazo.

The project ended up paying the musicians triple union scale because of their relative unfamiliarity with Simon and his prior works. In addition, the producer team gave writer royalties to those artists who had contributed significantly to the composition of the songs. Producer Ray Halee later said of this effort, “The amount of editing that went into that album was unbelievable […] without the facility to edit digital I don’t think we could have done that project.”

Halee added, “The bass line is what the album is all about. It’s the essence of everything that happened.”

As it happened, Simon’s record label, Warner Bros, was less than engaged in the project, seeing Simon as a bit of a has-been, but that gave Simon and Halee that much more creative freedom in the lead-up to the finished product.

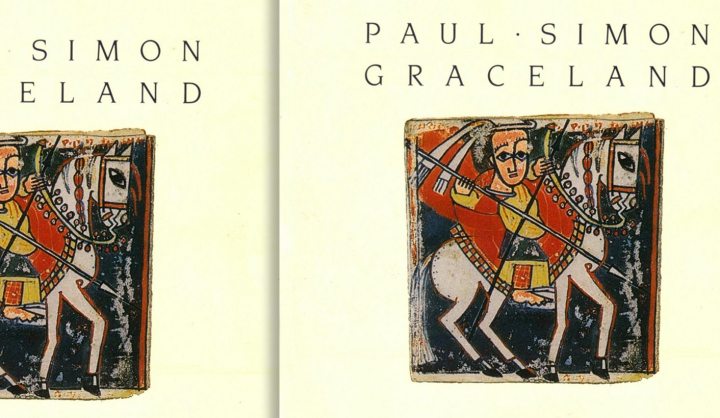

The resulting album, Graceland, was released on 25 August 1986 – 30 years ago next week. It became a huge global hit, amid great critical acclaim for its new musical pathways and its inclusion of such novel materials as South African mbaqanga instrumental riffs and rhythms and the close-order vocal harmonies, in addition to those Zydeco melodies and styles.

In sheer popularity, the single, You Can Call Me Al, and the Simon-Linda Ronstadt duet, Under African Skies, were especially well-received by listeners and purchasers almost everywhere. (This writer, then living in Swaziland, received gifts of both a vinyl record and a cassette recording from US-based friends who were eager to keep me apprised of “American music” – and its sudden “Africanisation”.)

Watch: You can call me Al – Paul Simon, Graceland

Climbing worldwide charts, it became #1 in many markets, including the UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, and was a #3 hit in the US as well, and eventually gained 5x Platinum certification. And yet another seven million copies sold internationally, making it Simon’s career best-selling album. With this recording, Simon was back in the game and pretty much right on top of it as well, with a Grammy Award for Album of the Year in 1987 and a Grammy Award for Record of the Year for the title track the year after. The enormously successful Graceland tour followed as well.

Watch: Diamonds on the soles of her shoes – Paul Simon and Ladysmith Black Mambazo

Still, criticism followed as Simon was briefly placed on the UN Special Committee on Apartheid’s list of artists co-operating with South Africa – until a variety of South African artists and other notable musicians spoke out in his defence. As Robin Denselow in The Guardian recalled of musicians placed on the list, “Those who did so were accused of breaking a UN-approved cultural boycott, which had been in effect since December 1980. After all, the wording of Resolution 35/206 was surely clear: ‘The United Nations General Assembly request all states to prevent all cultural, academic, sporting and other exchanges with South Africa. Appeals to writers, artists, musicians and other personalities to boycott South Africa. Urges all academic and cultural institutions to terminate all links with South Africa.’ ”

At the initial London launch of the film, Under African Skies, marking the 25th anniversary of this album, Denselow wrote, it was inevitable Simon would be asked about his co-operation with South Africa back then.

“That was the question he would inevitably be asked at the Mayfair launch, but he clearly wasn’t happy about it. He had no regrets, he told us, because he hadn’t gone there to perform…” but to bring South African musicians and music to the world.

Denselow added, “That, surely, didn’t answer the question, and so I then asked him whether he had taken any advice before making the decision to go. He replied that he had checked with the veteran civil rights campaigner Harry Belafonte, who ‘had mixed feelings … it was the first time that he had dealt with someone not going to perform but to bring back the music’. It later became clear that Belafonte had told Simon to ‘go and talk to the ANC’, advice he clearly didn’t take. When I pressed him further, he suddenly came out with a quite remarkable outburst, explaining his view on music and politics.

“‘Personally, I feel I’m with the musicians,’ he said. ‘I’m with the artists. I didn’t ask the permission of the ANC. I didn’t ask permission of Buthelezi, or Desmond Tutu, or the Pretoria government. And to tell you the truth, I have a feeling that when there are radical transfers of power on either the left or the right, the artists always get screwed. The guys with the guns say, “This is important”, and the guys with guitars don’t have a chance.’ I remember him looking round the hall as he added: ‘I haven’t said that before.’ ”

Artists Against Apartheid activists, including its co-founder Dali Tambo, complained at the time that Simon’s help to a few dozen artists didn’t outweigh the harm he was doing for the greater cause. Deneslow remembers, in his review of the film:

“Then the PR battle swung the other way, thanks not to the ANC, but to leading black South African musicians who had been closely associated with the anti-apartheid struggle. Hugh Masekela, exiled from South Africa because of his attacks on the apartheid regime, had known Simon since the 60s; he had appeared alongside Simon and Garfunkel at the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival. He suggested that they tour together, in a show that would include an array of black South African musicians, including the country’s finest female singer Miriam Makeba, and that songs from Graceland should be performed alongside black South African music.”

Watch: The Boy in the Buble – Paul Simon Graceland

Well beyond any political controversy, musically, of course, Simon had broken new ground in contemporary music, with his effort to vastly enlarge the perimeter of pop with an infusion of world music. Classical composers had, of course, been mining the folk musics of their world for hundreds of years, from Mozart to Schubert to Dvorak to Bartok and Kodaly, and with American composers like Aaron Copland in his archival wanderings through American folk melodies.

Moreover, musical explorers like John and Alan Lomax had recorded a wide range of American material for the Library of Congress and South Africa’s Hugh Tracey provided many hours of African musical material now increasingly dying out in their own homelands. Some record companies such as Nonesuch (now part of the Smithsonian Institution) have made invaluable contributions to preserving and distributing this material.

Watch: I know what I know – Paul Simon Graceland

But Simon’s contribution was to work with new material collaboratively as part of the total creative process, rather than simply dressing up a folk tune as a pop song, or using folk riffs to decorate his own music. Following Graceland, a second such collaboration followed in 1989, the Brazilian music-flavoured The Rhythm of the Saints. While it was not the massive phenomenon Graceland had been, it was still a major success and it created the rationale for another international tour for Simon and his fellow musicians.

And this is where Simon and my own fortunes drew together.

Watch: Homeless – Paul Simon and Ladysmith Black Mambazo

By this time, in 1992, this writer was the US Cultural Attaché in South Africa; the apartheid era was about to draw to an end; and Nelson Mandela had been released from his quarter century-plus incarceration and was on course to become the new president. In our office, we were working carefully to position a prestigious American cultural group as the first group to perform in the “New South Africa” being born.

Our negotiations with the ANC, the PAC, and even Azapo, had been brought to a nerve-wracking but successful conclusion to gain their support for such a visit, the relevant cultural bodies were finally on board, the funding was coming together, and even the renovated Civic Theatre in Johannesburg (closed for five years) had been secured as a venue, with the proviso that the city would make serious changes in its management. The New York City-based Dance Theatre of Harlem (the DTH), the lauded all-African-American ballet troupe, had signed on to make this first foray (including in its cast three black South Africans who had never before been allowed to dance professionally in their home nation).

When Paul Simon arrived in Johannesburg, he scheduled an initial press conference to explain his plans – plans that included a big concert in Ellis Park Stadium. For whatever reason, after he spoke, he turned his microphone – and his gathered media throng – over to a group of young men from the Azanian Students Movement, Azasm, who promptly excoriated Simon, the tour organisers, and anyone who had agreed to endorse this upcoming concert. The press conference adjourned in a shambles, with local and international concert organisers uncertain whether Azasm’s threat to shut down the concert was just so much bluff – or the real deal. The complication, of course, was that Simon did not, precisely, have written confirmations of support from all the various liberation groups – and the formalities of that UN cultural boycott apparently still held.

Given his previous run-ins over this same question, there were now anxious meetings as organisers wondered if they should just cut their losses and pull the plug on it. For our part, we were increasingly concerned that an ignominious collapse for one international, US-based cultural project would almost inevitably have ill-humoured repercussions and embarrassments for our own ongoing plans for the DTH. Things had a way of getting out of control quickly back in 1992.

Taking a chance, our colleagues (and seniors) agreed that if we could couch it as a sign of respect for a famous visiting American musician, the ambassador could then host a welcome reception for the tour – with urgent invitations going out to senior figures in the liberation movements, the domestic and international media, and some of the country’s best known cultural figures such as Miriam Makeba, now back in the country. This embrace – and the party – would demonstrate that the preponderance of South Africans strongly supported Simon’s visit, looked forward to his performance, and that they endorsed the idea that culture had a healing power and would serve to move the country forward, not backwards. That was the plan – and the hope – since we clearly saw that we had a real dog in what we thought might well be a very real fight.

Sometimes one has to take a chance.

On the night of the party, we ended up riding with the entire Simon entourage in a chartered luxury bus, escorted by a fleet of South African Police vehicles, to Pretoria. To our astonishment, pretty much the entire guest list (plus a few dozen or so uninvited guests who simply took the chance to be part of an historic moment) pitched up as well, everyone had a great time, and Simon’s tour was rescued (even though someone did set off a low-grade pipe bomb outside the door of the local promoter’s offices, early one morning).

And so, on the night of the concert, the writer and his family, together with a gaggle of South African musicians who had been involved in the original Graceland recordings, shared a skybox at Ellis Park. Wandering around in the box, in a perfect collision of the old and new South Africas, while we (along with tens of thousands of others) danced to the music of You Can Call Me Al, there was also Louis Luyt (the industrialist who had been so deeply entangled in the apartheid regime’s Information Scandal) who greeted all the skybox guests (it was his private box, after all). Luyt spent the evening nibbling at the buffet spread he had set out for everyone to enjoy and surveying the denizens in his skybox, while we watched the old South Africa dance and sing itself away through the evening. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider