Maverick Life

Written on the Soul: Sylvia Vollenhoven on being coloured and listening to ancestral voices

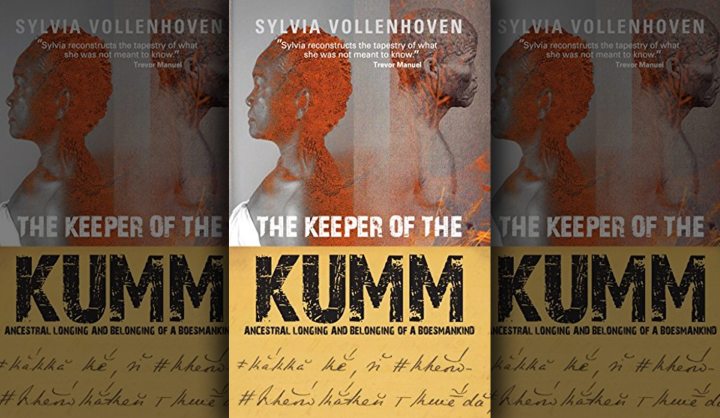

Veteran journalist Sylvia Vollenhoven’s just-published spiritual and political memoir, The Keeper of The Kumm – Ancestral Longing and Belonging of a Boesmankind, arrives at a critical moment in the post-apartheid deconstruction of identity, what it means to be Black, African or a First Person in South Africa. The memoir dovetails beautifully with the stream of consciousness that has been released in the slipstream of Wayde van Niekerk’s spectacular Olympic victory. By MARIANNE THAMM.

Google Wayde Van Niekerk and the words “on being coloured” and 124,000,000 results pop up in less than 0.04 seconds with headlines like “Why Coloured People need this Wayde Win”, “#ColouredExcellence: How Wayde van Niekerk’s victory challenges Stereotypes”, “Wayde van Niekerk is black! says sad Mngxitama” and “Should we care that Wayde van Niekerk is Coloured?”. “Coloured” began trending on Twitter soon after Van Niekerk’s world record-breaking 400m sprint in Rio on 15 August.

Why Wayde? Why now?

There have been others who have gone before – excelled in academia, sports, politics, music, journalism, the arts, cooking, comedy, literature – everything really. “So-called Coloured people”. Coloured people.

Because it is time.

Because the youth of RMF and FMF – the children of Biko, Sobukwe, Fanon, Baldwin, Davis and more – present and past black intellectuals and activists – are done with chipping away and are tearing down the edifice. Vollenhoven’s autobiography, then, arrives just as the planets, the stars, the ancestors and the people of South Africa who have come after them are ready to receive it.

“The people labelled coloured are mostly excluded from the narratives of nationhood that South Africa is constructing. It is never openly stated but I have had it spelled out to me in many ways throughout my life. I have lived in a coloured world with few intrusions from black or white people. I’ve been to coloured schools with kids from the Cape Flats who spoke about other races as if they inhabited another country,” writes Vollenhoven.

She adds that “we wear apartheid race classifications like tattoos on hidden skin. South Africans have a way of doing rapid calculations based on subtle textures and tones, beyond the reach of outsiders. When the computing is done, we adjust our behaviour according to the all-important tag we have allocated to the other person. Of all these tags that hint at identity, the one that has caused me the most harm is ‘coloured’. Decades of the new South Africa and colouredness is still a daily insurance of being marginalised. Reverberations of a heritage of genocide and dispossession.”

That’s why Wayde van Niekerk.

Vollenhoven is an anomaly in the South African media landscape. A black woman who grew up in apartheid South Africa, Cape Town in particular, in the ‘50s and ‘60s and found herself working in the newsrooms of the then segregated media world of the 1970s and 1980s. A black woman in a newsroom back then was almost unheard of. There was only a handful including Nomavenda Mathiane, Thokozile Masipa (later the Judge), Zubeida Jaffer, Joyce Sikhakhane and Sophie Tema, all of them pioneers of sorts.

Vollenhoven pushed many boundaries, marrying a white man when it was illegal to do so, and using her indistinguishable accent and Afrikaans-sounding surname to surprise many who encountered her – including the leader of the then right-wing Conservative Party who granted her an interview thinking she was white and Afrikaans. He couldn’t bring himself to shake her hand when he finally met her.

As a witness to history, Vollenhoven recorded or was present at some of the major events of the 20th Century including the 1976 student uprisings, the resistance of the 1980s, the slow-burn 1990s , the release of Walter Sisulu and Nelson Mandela, and the road to 1994. Vollenhoven worked for the then “coloured” Cape Herald, the “coloured” Sunday Times Extra, and then as a correspondent for the Swedish newspaper Expressen. Later she worked at the SABC during its most exciting transformation in the mid 1990s.

The writer soon realised she was everything to everyone. After her arrival in Jo’burg for the first time to attend the journalism cadet school in the 1970s she is assumed to be Zulu. Elsewhere on the continent when she travels, she is always mistaken for a local. She is a shapeshifter, she begins to understand. Part of it all but still not. The insider outsider.

What she is also, of course, is a woman, and this attracts a considerable amount of unwanted sexual attention, particularly in Neanderthal 20th Century newsrooms.

It is the Black Consciousness of Biko – which she encounters through colleagues in Johannesburg – that temporarily comes to contain and frame her, helping her to escape stifling apartheid race classification and providing political direction.

While this life as a journalist, a life fully engaged with the violence and the brutality of the physical landscape that surrounded her, certainly features in her tenderly rendered memoir, it is Vollenhoven’s journey inwards that is the most compelling and liberating thread and that buoys the thoroughly engrossing narrative.

Vollenhoven vividly traces her beginnings as the illegitimate firstborn child of Eileen Magdalene Petersen and Ebrahim Hendricks, a Muslim. Eileen’s mother and Sylvia’s devout grandmother, Sophie Peterson, disapproves of the union and cuts all ties with Ebrahim. Later Sylvia’s mother marries Freddie Vollenhoven, a surname Sylvia adopts.

The writer’s rendering of the characters who populated her early childhood are magnificent. She conjures the life of the hardships, joys and travails of a family classified by apartheid, ambitions limited, room to move and breath severely curtailed and cauterised.

Sophia Petersen’s parents were farm labourers from Wellington and most of her life she worked in the kitchens of rich white people. This she has done since childhood. And while there is, below the surface, a river of pain that flows through it all, Vollenhoven captures the ebullience and verve that masks it.

But all was not well.

For years Vollenhoven had suffered from a variety of ailments. There were rages and confusions that saw her lingering in psychiatric wards. There was a constant discomfort, an unease, a dull ache, as if her skin did not quite contain what was happening within. So much so that she eventually finds herself partially bedridden.

Tired of the routine rounds of medical intervention she opts for something different. She does what the majority of black South Africans do – consults a sangoma. Only hers happens to be a white healer, Niall Campbell.

Vollenhoven writes:

“I have been brought up to abhor these saviours of African sanity. Niall, the Botswana-born son of a Rhodesian policeman, is a qualified diviner, a doctor of traditional ceremonies as well as institutions and my spiritual teacher.”

It is then that she finds the Kumm – the story. This story.

“A story is a medicine for a person,” Niall says and the resultant memoir is a stitching together not only of Vollenhoven’s lost history but also that of so many who share her past of dispossession, eradication, humiliation and brutality.

Vollenhoven writes:

“Crossing over the barriers between worlds requires a process of reduction, letting go of the things of your old life.”

And she lets go, completely, surrendering to the ancestral voices that have been whispering and calling. Here she finds and traces the ancient wisdom of the Bushman visionary //Kabbo who lived in the 1800s and who travelled to Cape Town and the Bleek family of Wynberg who subsequently recorded his stories and visions. Today the Bleek/Lloyd Archive is housed at the University of Cape town and consists of over 12,000 handwritten pages and hundreds of notebooks of records. The Lloyd-Bleek collection of San folklore was entered into the UNESCO Memory of the World Register in 1997. As Vollenhoven has noted, “It is a heritage that is not known to most of the descendants of //Kabbo and the /Xam-ka !ei people whose language has been wiped out.”

Keeper of the Kumm is a bold and brave attempt at self-discovery, in fact of self-recovery. It is a spiritual book, a political book, a book filled with magic, dreams, visions, love and laughter and an unstoppable urge towards healing deep and ancient scars that cut across the ages.

Vollenhoven writes:

“We have been stripped of our ancestral places and our names. We are largely ignorant of our heritage and true identity. But if we search with open hearts, our rituals and stories can revive us.”

And she ends:

“If Africa is the birthplace of all humanity, then we are all children of the San.”

Reading Vollenhoven’s autobiography is an experience. A little like being present at a ritual where the spirits linger. Once you pick it up, you can’t put it down. And you might emerge at the end of it with a new vision of where we live, connected through a tissue of time, to what has gone before and what must still arrive. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider