Maverick Life, South Africa

Ashley Kriel: The struggle of memory against forgetting

Twenty-nine years ago, Ashley Kriel was killed by apartheid security forces. Earlier this year, the Hawks announced they would be reopening the investigation. For the family, it may just be the closure they have been waiting for for three decades. MARELISE VAN DER MERWE speaks to the filmmaker who has been documenting his short life for the past six years.

He fell from the ninth floor

He hanged himself

He slipped on a piece of soap while washing

He hanged himself

He slipped on a piece of soap while washing

He fell from the ninth floor

He hanged himself while washing

He slipped from the ninth floor

He hung from the ninth floor

He slipped on the ninth floor while washing

He fell from a piece of soap while slipping

He hung from the ninth floor

He washed from the ninth floor while slipping

He hung from a piece of soap while washing

– Christopher van Wyk, In Detention

In May 1987, under a State of Emergency, South Africa held its general elections, the National Party for the first time facing a serious challenge from the Conservative Party under Andries Treurnicht. Two months later, 20-year-old anti-apartheid activist and MK leader Ashley Kriel was shot dead at a “safe house” in Athlone.

In 1997, Jeffrey Benzien, his killer, testified before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. He couldn’t remember exactly whom he had tortured and how, he said. “If I say to Mr Jacobs I put the electrodes on his nose I may be wrong,” he testified. “If I say I attached them to his genitals, I may be wrong. If I say I put a probe in his rectum, I may be wrong. I could have used any one of those methods.”

Benzien was best known for the “wet bag” torture method of asphyxiation, more recently known as waterboarding; one of his other victims recalled he had shoved a broomstick up his rectum. “There were beatings, too,” the New York Times reported in the ’90s, “and some people were hung for hours by handcuffs attached to the window bars in their cells”.

In 1999, Benzien was granted amnesty. Alongside numerous torture offences, he was found to have committed perjury at the inquest proceedings on Ashley Kriel’s death. Post-apartheid, he was quietly downgraded to a security job at the Cape Town International Airport.

But Benzien’s crimes – and Kriel himself – are not staying buried quite so easily. In March 2016, the Hawks announced they were reopening the investigation into Kriel’s shooting, the family having insisted upon it after fresh details of the killings were uncovered. If sufficient evidence were uncovered, it could result in a murder charge.

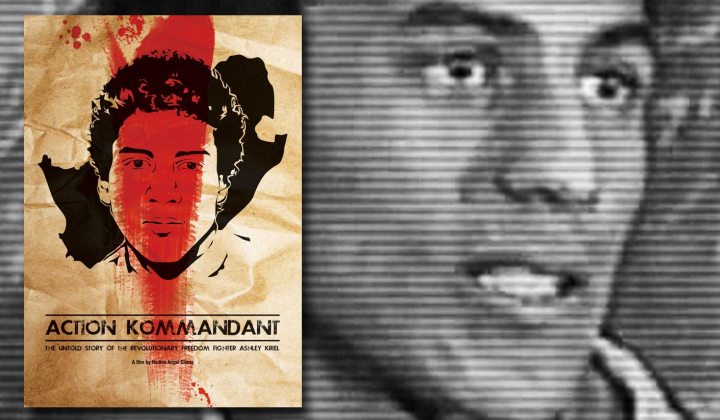

Conducting an unofficial investigation was young filmmaker Nadine Cloete, who had been working on a documentary about Kriel’s life, Action Kommandant, which was screened at Encounters and the Durban International Film Festivals this year. The film, although fresh from the starting blocks, has already fetched multiple awards.

At the age of 23, while working as an intern for Rainbow Circle Films, Cloete stumbled on some footage of Kriel. She couldn’t let go of what she saw. Growing up, her father had told her of some of the Athlone heroes: Kriel, Robbie Waterwitch, Anton Fransch, Coline Williams. She was small. She didn’t fully absorb it. She was barely more than a toddler when Nelson Mandela was released. “You had an idea,” she explains. “It was a big thing to be told these people died for freedom. And in 1994, you understand that your parents are voting, that they have to vote because this is what people died for. In terms of that, you understood it – that there was a real sacrifice.”

But the full understanding was gradual. In 1990, she and her family were living in Germany. Upon Mandela’s release, friends threw a party for her family. “There were ANC flags,” she recalls. “And then in 1992, we came home, and I had been used to being friends with whoever – and then it was having to go to school in Heideveld and only be friends with one kind of person. And then the hopes and excitement around 1994.” After 1994, Cloete changed schools, her social circle expanded; although she was young, she understood that something fundamental was changing.

And always, in the back of her mind, were the stories told to her by her father when she was growing up. When she stumbled on the footage of Kriel, it grabbed her and wouldn’t let go.

Watch: Action Kommandant trailer

At a recent screening, an audience member raised her hand and told Cloete how much it meant to her to see Kriel’s family – in particular his mother – depicted with dignity. Unfiltered, untranslated, and treated with the utmost respect. “I didn’t know how to react to that,” Cloete told Daily Maverick. “Must I be shocked? Touched? Offended? And then it occurred to me: someone is saying something I have experienced my whole life.” Cloete earlier explained, “History is so closely linked to identity. As a person of colour your identity has been messed with. Your language has been colonised. Your history? You’ve been lied to about it – just about everything.

“The story of Ashley, his comrades and the youth, was something I took really personally because I felt I didn’t know about this. All I see about myself are these negative images. I felt like this story is important because it puts our people in a very positive light; that we are heroes and warriors, not drug addicts and gangsters, which is the main image that is pushed.” For Cloete, the fight to reclaim education – the stories that are told about who we all are – didn’t die with the 1976 generation, and it’s 100% appropriate that Action Kommandant was released on the 40th anniversary of the Soweto uprisings. Youth, she believes, remain primary agents of change, whether it’s 1976, 1986, or 2016. She recalls being told about the expression So dronk soos ‘n kleurlingonderwyser in an old Afrikaans textbook; she is shocked to hear that this writer’s textbook included both that and Jy’s a witman (you’re a good guy).* She took part in the initial Rhodes Must Fall discussions, feeling that as a UCT graduate, she should take an interest in the direction university education was going, and that the struggle was much bigger than any one issue. Her short film Miseducation addresses what Cape Flats children learn outside of school, including that which they should not know. Change, she says, takes time.

“A journalist mailed me a question asking where I think South Africa will be in 10 years’ time,” she says. “I ended up not replying, because I couldn’t think what to say.”

For Kriel’s family, time has changed everything and nothing. The loss, says Cloete, at times appeared so raw that she had to take breaks from filming as she risked becoming too emotionally involved. Although she felt it was a huge honour to tell the story, it was also a huge responsibility. “When I first started with the interviews, I was maybe 23. To be that young and hold that kind of space, where you are interviewing someone and it is so emotional, really raw – it’s something else. If I didn’t have friends to speak to, I would have fallen apart. Next year, he would have been dead for 30 years. Yet when people speak about him, it’s like it happened yesterday. Emotionally, it did take a toll.

“In terms of memory, we were never told these things. They are not in our history books. Our history was under the carpet. And suddenly I was learning it. I felt angry. Even now, from young people who watch this film, they will say they felt angry or ashamed that they did not know. But it is not our fault. Nobody should feel that way. It was tough on many levels.” The bond Cloete formed with Kriel’s sisters, Michel Assure and Melanie Adams, will not be shaken easily. Not after what they have gone through together, not after what Cloete has had to say on their behalf.

“Since the day I went to the crime scene, I knew my brother was killed,” Assure said earlier this year. “They [security police] had threatened to skiet hom plat soos ‘n haas.”** In Assure’s version of events, when she arrived at the scene – a ‘safe house’ where Kriel had been in hiding – the walls were covered in blood spatter. There was blood in the backyard, on the patio and on a spade. Assure is sure her brother was beaten with it.

First she was told Kriel shot himself. He was shot in the back. Later the family was told he was accidentally shot during a scuffle after he produced a firearm.

Kriel – beautiful, charismatic Kriel, with his curly hair and mischievous giggle that belied such a deep commitment to his fight for freedom – had understood, too early, that he might die. And yet it seemed unreal, too. In March this year – the same month the Hawks announced the investigation would be reopened – Assure said she initially thought the police were playing games with the family when they said her brother was dead. “I thought: ‘The police are trying to play this trick on us. They’re going to show me a mutilated body or something horrible just to unnerve me or just to do something bad because that’s what they did to the families.’” It wasn’t a trick. Cloete says seeing the pictures of Kriel’s body was something she will take some time to get over.

“Seeing him handcuffed in those images was crazy,” she said in an earlier interview.

Kriel’s death was a devastating blow to his family, whose father had already been stabbed to death. He had been behind a major recruitment movement at three high schools and had gone on to become a formidable soldier. But perhaps hardest, says Assure, is the fact that they were failed twice: once by the police inquiry into his murder, and the second time by the TRC. “Ashley got a raw deal,” renowned forensic scientist Professor David Klatzow said of the investigation into his death.

According to the Cape Argus, Klatzow “concluded [in March 2016] that the young Struggle hero was murdered by security police who fabricated a story to the TRC to cover up their involvement in Kriel’s death.” But this was not new information. Years ago, Klatzow testified that Kriel’s murder was being covered up by police and that Kriel had not just been shot in the back, but had been shot from some distance. Like a rabbit. City Press has reported that Klatzow has in his possession an “old, leather-bound book with pages of scrawled notes about Kriel’s death” including photos of his body, copies of documents and a conspicuously sketchy autopsy.

Benzien, against the assertions of Kriel’s family, told the TRC he and his colleague, one Constable Ables, had had no intention of shooting Kriel. Kriel, they asserted, pulled out a firearm. After the ‘scuffle’, Benzien radioed for help, but Kriel was dead.

And then he received amnesty. He has not spoken to media since.

Oral historian Professor Sean Field has argued the failure of the TRC to deliver on its promise of national healing. “Commentators within and outside the TRC repeatedly stated that ‘healing’ would ‘lay to rest’, ‘settle’ or ‘bury’ the past. And as [Mamphela] Ramphele rationalised it, ‘A medical metaphor best captures what I perceive to be the issues facing us in relation to “appeasing the past”. An abscess cannot heal properly unless it is thoroughly incised and cleaned out.’ However, it is precisely this bio-medical notion of ‘healing’ that is problematic in my view,” he writes. Healing cannot be foisted on a nation vicariously nor on the individuals within it. Mourning is an entirely personal process and often – as many of us know – never fully realised. Where there is obfuscation and denial, it can only be more difficult. What can the families of victims do or think when the perpetrators fail to give answers?

Some things change, some things stay the same. “The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting,” Milan Kundera wrote in The Book of Laughter and Forgetting. In some ways, the struggle of young firebrands over the last 40 years remains the battle for narrative. Cloete uses the vocabulary of student activists: she speaks of decolonisation, the promise of free education. The fight is so far from over, she says.

In this respect, Cloete and others of her ilk are activists. In a time of struggle against looming censorship, storytellers and soldiers for justice are heroes. Those who remind us that decades after Ashley Kriel was shot in the back, dozens of miners can suffer the same fate. Those who remind us that where the public broadcaster wants to gloss over protests and public dissatisfaction in election season, honest inquiry still matters. They remind us that stories are not just stories.

At a screening of Action Kommandant over the weekend, commemorating the 20th anniversary of Kriel’s death, Ahmed Kathrada Foundation executive director Neeshan Bolt said not enough had been done to commemorate Kriel’s life and contribution. Cautiously, Cloete concedes that some apartheid-era heroes are more unsung than others. “If you didn’t die in the Struggle, it doesn’t mean you didn’t give your life,” she says carefully. “We need to be doing more.” It’s a touchy subject; she doesn’t want to delve into it too deeply. But for the loved ones of many lost activists, including Kriel’s own recruits Waterwitch and Williams, closure remains elusive and celebration can be touch-and-go.

For Cloete, the task at hand is to screen Action Kommandant as broadly as she can. She’s still trying to raise funds to buy additional copyright; at the moment she only has rights to screen the Associated Press footage at film festivals or for educational purposes. By the 30th anniversary of Kriel’s death, she wants to be able to distribute DVDs. It’s hugely important to her to tell the story of his life, not just his death, even though the renewed investigation of his death may bring some peace to his family.

“In a well-structured narrative, there is coherence between a story and its ending,” write Chris van der Merwe and Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela in Narrating our Healing. “The end, in a way, contains the whole preceding narrative. Similarly, in life, the end is foreshadowed by what precedes it. A great trauma, with its destruction, is like a premonition of death. Trauma, however, can give rise to new meaning, just as human life can continue, even after death, to spread its significance.” Cloete may have delivered just that coherence to both the beginning and end of Kriel’s story. And therein lies great significance. DM

* Translations: As drunk as a coloured schoolteacher/ You are a white man.

** Shoot him flat like a rabbit.

Photo: Ashley Kriel and the poster for Action Kommandant.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider